What is reverb? The reverb resource for audio engineers of all levels

What is reverb in music? Using audio examples, we explain reverb: types of reverb and how musicians, producers, and engineers can use it.

What is reverb?

As musicians and audio engineers, we often work with reverb, sometimes without knowing much about it. In this article, we give a comprehensive overview of everything you need to know about reverb, with links out to additional reverb reading and resources.

What is the definition of reverb?

Reverb is created when a sound occurs in a space, sending sound waves out in all directions. These waves reflect off surfaces in the space, decaying in amplitude until the reflections eventually die off. Without extensive sound-proofing, most spaces will produce many closely spaced reflections, which reach the listener shortly after the initial dry sound. We hear this series of reflections as a single, continuous sound, which we call “reverb.”

What does a reverb do in music production?

There have been plenty of acoustical and mechanical methods for creating reverb in music production. Today, modern productions typically use digital reverb (hardware units, or software plug-ins like Aurora,

Neoverb

Digital reverb types

You’ll probably come across two types of digital reverbs—algorithmic and convolution. Most digital reverbs use either algorithmic or convolution reverb, but some, like the Reverb module in

Nectar 3 Plus

Algorithmic reverb

Algorithmic reverb simulates reverb through a series of calculations (an algorithm). By creating reflections mathematically, you can imitate the sound of real spaces, or design new sonic environments that would be impossible to create otherwise. Examples of algorithmic reverbs include our brand-new Aurora plug-in, as well as Neoverb, the venerable Lexicon reverbs, Sonnox Oxford Reverb, and Exponential Audio reverbs.

Convolution reverb

Convolution reverb, also known as IR or sampling reverb, creates reverb by processing an impulse response (IR)—a recording of a signal that was played in an actual room or sent through a piece of gear. This signal contains all frequencies (often a blast of white noise, starter pistol, or even a sine wave swept across the audible frequency spectrum), which is done to trigger the full acoustic response of the space.

Doing this allows us to analyze how the room or gear affects the signal over time. This analysis is then converted into a reverb profile, which can be applied to a dry sound. Nectar’s Reverb module creates the sound of the EMT 140 using IRs recorded from a real EMT 140.

Using convolution reverb, we can make things sound like they’re in real spaces (like the Sydney Opera House, for example). Examples of convolution reverbs include Audio Ease AltiVerb 8 and HOFA IQ-Reverb, though there are many more.

Note: When compared to algorithmic reverbs, convolution reverbs deliver more realistic reverb sounds, but require substantially more CPU resources, leading to more latency. Therefore, it’s best to minimize the number of convolution reverbs in a session.

Aurora, our newest reverb

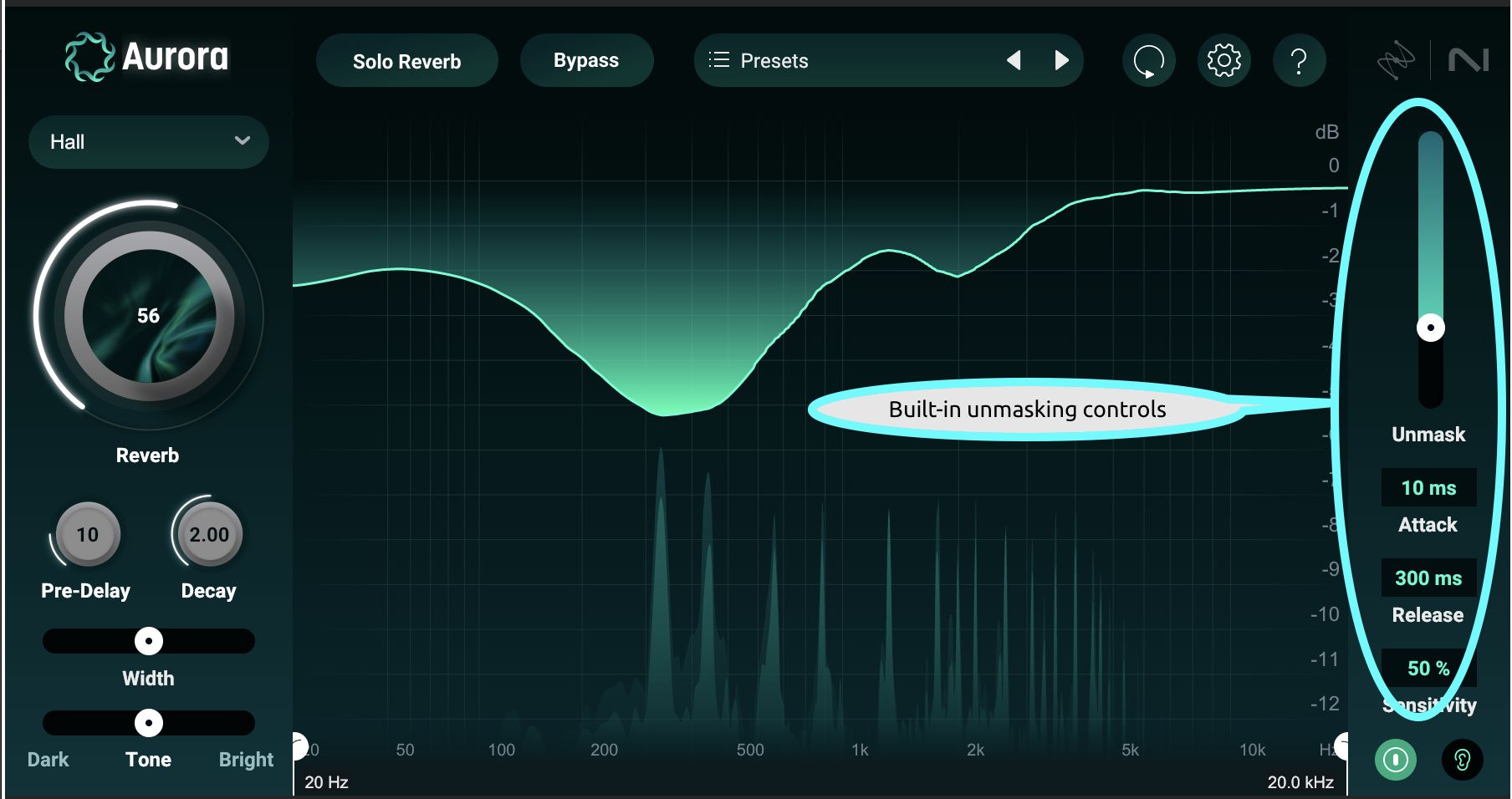

If you’re interested in the latest reverb we’ve brought to market, we’d like to take a beat to show off Aurora. This powerful, yet affordable reverb mines fantastic algorithms from Exponential Audio, making them exceedingly intuitive to use. More importantly, we’ve added our newest frequency-unmasking tech to speed up your workflow.

Many of the points we’ll cover below—from digital reverb controls to common issues when utilizing reverb—are handled efficiently and effectively by Aurora. The plug-in also sounds fantastic in subtle and dramatic applications. Finally, Aurora will sound at home in a variety of mixes, from the lush pop soundscapes we often encounter today, to aggressive tunes that require shorter ambiences.

Controls of digital reverbs

In digital contexts we have the ability to greatly customize our reverb sound. Below are some of the more common controls on digital reverbs.

Pre-delay

Pre-delay is the amount of time between the direct sound and the start of the early reflections—reflections that only bounce off one or two surfaces before reaching the listener. Larger rooms naturally exhibit longer pre-delay because it takes longer for the sound to reach a surface and reflect off of it.

Listen to the following clip to hear a dry snare followed by the snare with room reverb (with no pre-delay), then the snare with the same reverb and 100 ms of pre-delay. Notice the gap between the third snare hit and its reverb.

Decay time, a.k.a. ‘reverb time,’ ‘reverb tail,’ or ‘RT60’

Decay Time is the amount of time it takes for the sound pressure level (SPL) in a room to fall by 60 dB. If large and small rooms are constructed with the same materials, the large room will have a longer decay time. Although somewhat dependent on frequency, rooms with highly reflective surfaces like concrete or hardwood give longer decay times than rooms with absorptive surfaces like carpet or fabric.

The audio clip below contains a dry snare, then the snare with a room reverb set to a 400 millisecond decay time, then the same reverb with a two-second decay time.

Diffusion

Diffusion is the dispersion and density of reflections. Low values result in low reflection density, allowing us to hear individual reflections more clearly. High values result in increased reflection density and a more uniform wash of reverb. Use high diffusion for a smooth reverb or low diffusion for a more “chattery” reverb.

In the following example, the first snare hit features a room sound with low diffusion (notice the “chatter”), while the second snare hit has the same room sound with high diffusion (notice the smoothness).

Damping

Damping is the absorption of high frequencies in the reverb. Low damping values yield less high-frequency absorption, whereas high damping values produce more absorption of high frequencies. Lower the damping to allow high frequencies to decay for longer to create a brighter reverb sound, or raise the damping to choke the high frequencies and make a darker sound.

Listen to the following audio to hear a reverb with low damping, followed by the same reverb with high damping. Notice the difference in the high frequency content.

Dry/wet balance

The dry/wet balance sets the balance of dry (original) and wet (affected) signal leaving the reverb. Note: Instead of using a dry/wet blend knob, we went a different route when designing Aurora, our newest reverb plug-in.

Dry/wet knobs are a balancing act. They turn down the dry signal as the wet comes up in volume, doing so to keep the overall levels the same.

In Aurora, the dry signal always stays the same, and you simply add the amount of reverb you want to the original signal. This makes it easier to predict how any non-linear processors, such as saturators and tape emulators, will react to the effect.

Whether you’re using Aurora’s reverb control or a simple dry/wet blend, the amount of reverb becomes especially relevant when we get into best practices for using reverb.

Tonal controls

Many reverbs have built-in EQ and Filter parameters to better control the tonality of the overall effect. You may see high-pass or low-pass filters to take out muddy bass and fatiguing trebles. You may see a parametric EQ band to reduce low-mid bloat.

Like the sustain pedal on a piano, reverb makes every part of every sound linger. On a solo instrument, this might not be a problem. In a mix, however, this can quickly lead to unwanted frequency build-ups and frequency-masking issues in your arrangement.

That’s why Aurora was developed with a spectral-ducking algorithm to suppress unwanted resonances in your reverb.

Use the circled controls, and you won’t need to enact broad, sweeping changes to the overall tone of your reverb.

It’s likely that you’ve seen these settings many times before, probably on reverb plug-ins, pedals, and rack units. So, does that mean that two reverbs with the same settings will be the same? Decidedly not! Two different types of reverb with the same user-adjustable parameters will not sound the same.

What are the types of reverb? Step this way, please.

What are the types of reverb sounds?

When we say “types of reverb sounds,” we’re talking about the methods through which reverb is created. The following examples show the most common methods in action. No direct signal is included, so you can focus on the reverb.

The first three clips are simulations of acoustic environments. Incidentally,

Neoverb

Hall reverb

Hall reverb results from the unique physical characteristics of concert halls, which are typically large spaces acoustically designed for a long, smooth decay.

Room reverb

Room reverb results from the unique physical characteristics of smaller rooms like studios or living rooms, typically with shorter decay times and closer reflections.

Chamber reverb

Chamber reverb results from the unique physical characteristics of reverb chambers, which are reflective spaces such as corridors or stairwells designed to house a speaker and microphone configuration for triggering and recording the reverb.

Plate reverb

Plate reverb results from a vibrating metal plate. In a real plate reverb, a large sheet of metal is suspended in an enclosure. Multiple transducers—a small driver and at least one small contact microphone or pickup—are attached to the plate. Dry signal is sent from a console or audio interface to the driver, which causes the plate to vibrate. The contact microphone picks up these vibrations and outputs them for use in the mixing system. The larger the plate and the further apart the transducers, the longer the reverb time.

Without a built-in high-frequency rolloff, and because the spacing of reflections doesn’t vary as much, plate reverbs will tend to sound brighter and more diffuse, like in the example below.

Spring reverb

Spring reverb results from small vibrating springs. Like plate reverbs, spring reverb units rely on vibrations to create reverb. Dry signal is routed to a transducer, which is attached to one end of multiple springs. Signal passing through that transducer causes the springs to vibrate. Those vibrations are picked up by another transducer on the other end of the springs. The longer the springs, the longer the reverb time.

Halls, rooms, and chambers will have a three-dimensional quality due to the three dimensions in which sound can reflect (in those spaces). Plates and springs will exhibit a two-dimensional character as a result of the vibrational mechanics of the physical plate and springs.

How and when do you use reverb? Techniques and effects

Reverb can be found in nearly every modern production. Whether it’s the gated reverb on Phil Collins’ iconic “In The Air Tonight” drum fill, or Grimes’ ethereal reverb-filled vocals, reverb is inescapable. To understand how and why reverb is used, take a quick dive into the history of reverb in music production, and to understand the musical considerations for adding reverb, head here.

General tips for using reverb

Don’t just treat reverb as an ‘effect’ that you’re adding to a sound. You’re actually introducing a brand-new signal in the mix, one that should play well with others and be treated as its own mix element.

The standard way to practice this approach is to use return/auxiliary channels to add reverb, with the dry/wet balance at 100% wet—or with Aurora, to click the “Solo Reverb” button when using this new plug-in on your auxiliary returns.

This keeps all of your dry and wet signals separated, which not only allows us to more intentionally process our dry sounds, but also to independently process our reverb signal. You can always use insert reverb as a sound design tool, but it’s best to separate the dry and wet signals in any standard reverb application.

Like any other mix element, you’ll want to EQ your reverb signal, mostly to attenuate frequencies under about 200 Hz and above about 8 kHz. If your reverb has too much energy in the lows, it can smear your low end and prevent the clarity you need there. Too much energy in the highs, and reverb can make it difficult for vocals and lead instruments to cut through the mix.

EQ isn’t your only tool for getting reverb to sit in the mix. Head here to learn how you can use ducking and timing strategies to provide space without creating a fog of reverb over your entire mix.

If you’d like to forsake extraneous EQ and dynamics-taming plug-ins in your reverb chain, we encourage you to experiment with the following plug-ins:

Try Aurora for minimizing masking between any dry signal and its resulting reverb. If your vocal reverb is obscuring your dry vocal, Aurora can easily eliminate this problem.

Try Neoverb for minimizing frequency masking between any reverb and a different, conflicting instrument. If your vocal reverb is obscuring a synth part, Neoverb’s interplug-in communication can handle this issue.

Reverb in mixing

With so many options, how do you go about selecting the best type of reverb when mixing? Well, that’s a tough one, but we have a guide for that!

One reverb will never be the best one for everything. A reverb that you swear by for vocals may be terrible on drums. A reverb that normally slays on drums isn’t going to be ideal for all clients’ drums. Although choosing reverb is a subjective process, there are some solid points to start from. The following clips allow you to hear examples of appropriate and not-quite-ideal reverbs on various sources.

Note: Too many reverbs occurring simultaneously will usually make a mix muddy—and it will be hard to hear each reverb effect. Jump to “reverb mistakes and problem areas” to learn more.

Reverb on drums

With how varied drum kits can be, there isn’t a single, acceptable way to apply reverb to drums. Find what sounds right to you, but you can follow some general considerations that will help your reverb stay consistent in your mix.

First, consider that it’ll sound quite unnatural for each drum sound to be in a completely different room. You can certainly use different reverb sounds to give some of your drums sounds some character, but a single reverb for the kit can also help glue it together.

Just remember that low reverb on your kick should generally be avoided, so don’t send the kick to your reverb bus.

Given that drums are transient sounds, and that their impact comes from their ability to cut through the mix, you may want to duck your drum reverb signal a bit to the drum sounds. We hear reverb in the spaces between sounds, so this will help the dry drums cut through the mix, but still give them the sense of space that you want them to have.

Learn more tips for reverb on drums.

Pro tip: Watch out for too much low-frequency energy (below 100 Hz) in your drum reverb; it gets boomy fast and usually doesn't sound good!

Reverb on vocals

How you apply reverb to vocals generally depends on the vocal sound you want. Aiming for a washed-out vibe à la The Weeknd? You’ll probably need a longer reverb tail. Aiming for an in-your-face rap vocal? A short room reverb—or even no reverb at all—might be your best bet.

Mixing a genre with particular reverb standards, like spring reverb in dub and reggae? Give the people what they want! Or play with their expectations and give them something totally different.

Regardless of what reverb sound you’re using for vocals, the general reverb tips we’ve covered still apply: use EQ to prevent your dry vocal and its reverb from competing for important frequencies, and maybe duck the reverb a bit to the vocal itself.

As for tips specifically dealing with vocal reverb, you may want to perform additional de-essing before your reverb plug-in on your vocal reverb bus. This will prevent sibilances from hitting the reverb too hot. If sibilances are too loud, they’ll really ring out in the reverb, and become distracting in the mix.

You might also want to carve out room only for the topline in the center channel of your reverb. This will help make space for a mono topline vocal without sterilizing the reverb signal in the sides of the stereo field.

Learn more tips for using reverb on vocals.

Pro tip: Make sure you don't have too much high-frequency information in your vocal reverb, unless you want the sibilance to excite the reverb. You can roll off high frequencies in the aux send or roll off high end in the reverb itself.

Reverb on instruments (guitars, keys, synths, etc.)

Again, the general reverb tips we’ve covered still apply for instruments. Sustaining instruments, like sustained notes on guitars or keys, may compete with reverb tails, requiring some fine-tuning to keep the mix clean. Short, transient instruments, like mallet instruments, will leave more room for reverb tails to propagate.

And if your instrument is playing chords, excessive reverb may smear chords over each other, potentially making the chord progression more difficult to hear.

Pro Tip: Delay might be preferable to reverb for some instrument parts. For example, the guitar often employs a combination of long, sustained notes and faster, melodic material with more transient content (think heavy metal shredding here). Depending on the vibe you’re going for, reverb has the potential to add too many reflections, compromising intelligibility. In these cases, a more modest, subtle delay may be more effective for adding space and depth to the guitar track.

Reverb on bass

Because low-end clarity is super important for a clear mix, it’s often best just to leave your bass dry. You can use reverb as a sound design tool for some bass sounds (e.g. giving aggressive electronic basses a sense of space, as they may act as lead instruments in some tracks), but you should keep reverb signal mostly limited to mid and high frequencies. Just make sure that your dry bass sound doesn’t compete with your reverb signal in the lows.

Using reverb as an effect

There are lots of different varieties of reverb effects—learn how to create some of them like background washes, realistic vintage samples, and more in this article, and explore some wild and wacky uses of reverb here and here.

The most common types of reverb effects you hear in a track are reverse reverb and gated reverb.

Reverse reverb effect

Reverse reverb is reverb in reverse (a fun technique to try on vocals and drums!). Rather than a splash of reverb decaying to nothing, it starts at nothing, then ramps up to an abrupt end. This is typically done by first reversing the sound that you want to ramp into, then applying a long reverb tail, converting that reverb tail to an audio clip, and reversing the audio clip. This creates a seamless transition into the dry sound and introduces its timbre before it plays.

Listen to the next clip for an example.

Gated reverb effect

Gated reverb is a non-linear reverb—rather than decaying smoothly into silence, its tail is attenuated swiftly by a noise gate. The result is often a short, explosive sound, as heard in the next audio clip. It’s useful for elongating percussive sounds, which increases their audibility without having to turn them up. The big snare sounds heard in a lot of ‘80s pop music were created with this technique.

Common reverb mistakes and pitfalls

Most mistakes around reverb involve using too much reverb overall, or at least too much to allow dry signals to feel clear, present, and full.

Reverb can create mud in your arrangement, making mixes that require a lot of reverb a nightmare to deal with. This is part of the reason we developed Aurora: we wanted to make a reverb with smart, built-in tools for handling frequency build-up, thereby speeding up your workflow.

Using multiple types of reverb or multiple spaces can compound the problem, making stereo image and the perception of space in the mix inconsistent. It’s best to minimize the number of different reverb sounds as much as possible, though it can be helpful in some cases.

Approaching reverb the same way in every mix is also another pitfall to avoid. Some genres have certain reverb standards, and it can also be refreshing to occasionally and intentionally break those standards too.

How do you use reverb for post production and other audio projects?

We’ve only just scratched the surface of using reverb in audio production. All the above tips will serve you well for music, but you might be working with reverb in a post-production context, mixing for anything from TV and movies to short films and podcasts.

Reverb serves a slightly different role when mixing audio for video, as it helps to create a sense of realism, making ADR, sound effects, and Foley actually sound like they’re in the original production audio. Because of this, your reverb decisions will mostly be driven by the scene you’re working on.

Also, because reverb behaves differently in different locations in a space, and because people and things may move around on-screen, post production involves a lot more reverb automation than music production. A reverb’s character, decay time, and panning location may change when something in the scene (or the camera) moves.

How can you remove reverb from audio? De-reverb.

Sometimes, you may have to deal with baked-in reverb in your audio, like the room noise you may hear in a DIY home recording. Unless you’re explicitly going for a DIY vibe, or unless the space you used for recording plays a big role in the sound (like a concert hall), you’ll want to minimize this reverb. If you try to add your own reverb to an already wet signal, you run the risk of creating a bunch of mud in your mix.

You can use gates, transient shapers, and EQs to minimize room noise, but you can remove even more room noise with some of the tools in

RX 11 Advanced

The takeaways

If you allocate some time to tweaking your reverbs, you’ll unlock some extra sonic goodness. Try them in mono, stereo, and experiment with extreme settings when you aren’t busy. Also, keep your ears open for interesting natural reverberation as you go about life!