10 Tips for Mixing Short Films

Mixing a short film can be intimidating for the novice engineer. Here, we’ll provide powerful perspectives and practical techniques for mixing short films.

Mixing a short film can be daunting for the novice engineer. Consider this article your step-by-step guide, and refer to it whenever you need to figure out how to mix a short film. We’ll walk you through how to budgeting your time, focusing on editing, and making the right individual moves within the mix.

1. Take the amount of time you think you need, and double it.

Read the above sentence, and really take it in: when working with a director, consider how much time it’s going to take to finish the movie, and double it if you can. At least add a couple days more than you think you’ll need.

In the indie world of short films, even getting the files to work can take longer than you’d expect. I’ve worked on quite a few short films and web series, some backed by production companies and others financed with sheer willpower. I can count on one hand the number of times opening an AAF or OMF session in Pro Tools has gone smoothly. Either the file is corrupted in some fashion, or re-linking the files becomes a carpal-tunnel-inducing exercise in mousing around a hard drive. This is not a problem unique to me—my peers experience it regularly.

Also, you never know what might happen during a session’s timeline. The director might decide they want looped dialogue to replace a line they can no longer use. You may get a new cut of the movie half-way through, which has certainly happened to me. Or, you may discover that a line of dialogue you thought was salvageable actually no longer works in the context of a processed mix.

I know time is a precious commodity, and availability can be the determining factor in landing the gig. Still, for your own sanity, try to get at least an extra day in your schedule. If you’re working with an experienced editor, and everything works fine out of the gate, the worst that can happen is you have extra time to mix.

I used to give the director quick deadlines, and found myself working all hours to achieve them. Now, I consider how much time it’s going to take, and add a few days on to my quote, depending on the project. This gives me more room to work.

2. Organize your session.

A short film can be anywhere from a minute to thirty minutes, in my experience. The last one I did—The Architect, for Alexandre Pulido—had around 20 scenes. Some scenes had multiple sound effects, as well as dialogue among three or more people, which of course means extra lav tracks. Furthermore, the OMF file I was provided had everything in stereo—even the mono dialogue tracks. This effectively doubled the track count.

Track count doubled

It could’ve been an ergonomic nightmare—if I didn’t organize my session. The first thing I did when I got the session into my preferred DAW was to organize and color-coordinate every track.

Project organized into separate scenes

Setting up markers for each scene and bus routing—more on that later—is also best handled at this stage. Take the time to do this now, because it makes the mix much easier as you progress.

3. Determine if the lav or the boom works best for the scene.

In most situations, you’re going to get audio from lapel mics on each actor, as well as audio from a boom mic that covers the whole scene. Yes, there are exceptions, but this is the general rule.

As soon as you’ve organized and color-coordinated your session, audition each track, scene by scene. This is essential because you may encounter one or more of a number of scenarios:

- The boom mic may sound best for the whole scene.

- The boom mic may not pick up one of the characters well, so you need the lav from that character.

- The boom mic may pick up too much room signature within the vocals themselves, so you need to use the lavs.

- The lavs are distorted beyond usability.

- The lavs and boom are out of phase, so you need to adjust if you’re using both.

Those are some of the dialogue issues that routinely occur. Take your first scene and make a snap judgment about each track as you listen. Then edit and mute regions, keeping an eye—and ear—on the overall balance. In this context, we’re referring to the balance between what sounds best and what works most efficiently.

Deciding between boom and lav recordings

Alternatively, you can quickly match the sonic characters of the boom and lav mics with a tool like

Dialogue Match

4. As you begin to work, keep your loudness standard in mind.

We must always consider how loud the final mix needs to be.

As per generally accepted standards, -23 LUFS is frequently your target goal for broadcast and radio. You don’t need a lot of compression to drive this level—thankfully it’s very forgiving, and allows for plenty of dynamism.

If you’re working with an established production company, they will often give you a loudness target—either one they must follow, or one they would like you to follow. If they do not provide a target, it’s always a good idea to ask.

However, you may find yourself working with a director who’s funding everything independently, without the help of such a company. The director will rely on two things: your opinion, and their own intuition.

Your opinion should be that the mix ought to stay at a healthy level, allowing you to be dynamic. The director’s intuition will invariably differ: they will want the loudest mix that will suffice.

Yes, this is the sorry truth, even in post.

So, if you have to deliver a mix that’s -16 LU or even higher—and yes, directors have often asked me for louder mixes on their films—you are in a bind:

You must deliver something relatively hot without making it an ear-fatiguing mess. This means you’ll need a fair amount of level-focused processing such as compression, but you must preserve a dynamic feel.

In general, I find the best techniques for achieving these goals are similar to those I’ve offered previously, particularly in my article on podcasting and my piece on preserving dynamic impact and high levels.

In summary, the best approach is to utilize intelligent gain staging and parallel compression whenever possible to bump levels without inducing ear fatigue.

Thus, each track might wind up with a little parallel compression to help bolster the levels, and each submix might also have parallel compression for a similar reason.

If you’re new to post, think of this scene-to-scene progress as something similar to mastering an album: just as no track should feel incongruous in an album, every scene should be informed by what comes before.

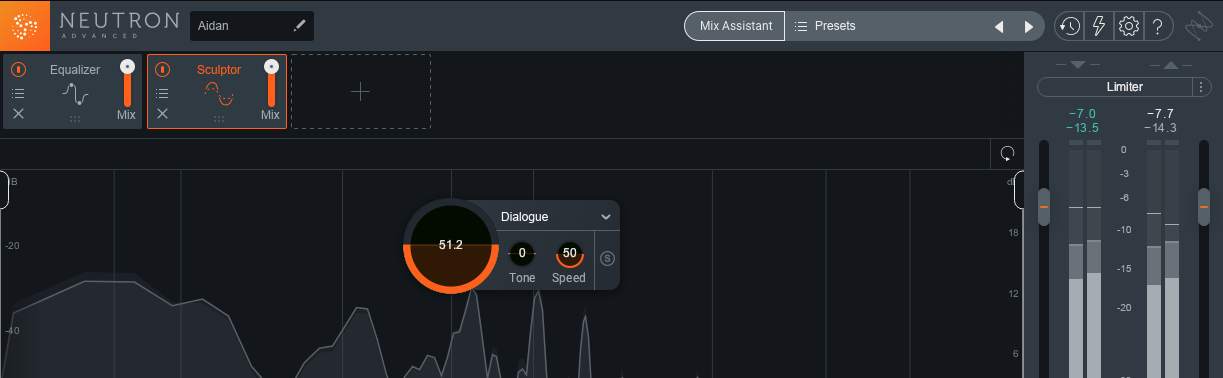

Now let’s examine a tool that helps us keep our scenes congruent as the film runs:

5. Consider using submix or bus processing.

Post production and music production are two entirely different worlds, but that doesn’t mean you can’t take techniques from the music world into your post environment.

The chief technique I utilize is bus processing. Every scene gets its own bus, allowing me to make broad changes to the scenes’ sonic interactions as needed.

A bus for each scene

I may have two scenes that take place in the same location, but exhibit different characters—or employ different mics.

Maybe the lav had problems with cloth rustle in one scene, but the boom had problems in the other. In this situation, having two submixes helps: I can copy and paste one setting to the other, and adjust as I go along to account for the individual elements. The EQ might change, but the leveling would be handled by uniform processors.

Now, what kind of processing do we see on the busses? In my workflow, I frequently use EQ and compression—and often that compression is in parallel. Sometimes I use reverb on a scene’s submix to blend the Foley and atmosphere with dialogue shot on location. You can read more about that technique here.

6. If your computer is light on CPU power, break scenes out into separate sessions.

My main computer can handle a film just fine, but my MacBook Pro? Not so much. Track counts, automation, bus processing, and multiple plug-ins all take processing power—especially when running a movie in the DAW all the while!

If you know your computer is a bit unstable the more you slam it, break your scenes out into separate sessions. Even two or three scenes at a time is a good compromise.

When it comes time to assemble the film, you can bounce each scene, load them all into one master session, and stitch them together with crossfades or overlapping fades.

Assembling the full film mix from bounces of each scene

Bounce the entire movie up through the session’s scene with each bounce; this is perhaps the easiest way to preserve the sync. If all the files start bang on the beginning, sync shouldn’t be an issue.

If your computer doesn’t have the CPU to handle a large track count, you probably can’t employ bus processing either. However, you can save bus processing for the final assembly using this breakout technique, processing directly to the tracks in the final session.

Now, is this an annoying workaround? Absolutely. But should you be held back by the tech you have? Absolutely not. If you don’t have the CPU to handle the film, you can use this technique to avoid turning down the project. Just make sure you don’t mess up the sync!

7. Never mess up the sync. Period.

You cannot mess up the sync. I’ll say it again: you cannot mess up the sync. If the lips don’t match the sound, you’ve failed the most basic part of the job!

At a minimum, you should lock your audio in place while editing, which is possible to do in Pro Tools and Logic. You should also be careful with plug-ins: sometimes latency compensation when bouncing something in place or rendering processing to a file can alter the timing a little.

Always keep an eagle eye on the film as you edit. If you notice the dialogue is off, save, then undo until the sync is once again correct, and save this pass as a new file. If you can’t find the place where it went off, you’re in trouble, and you may need to move things around by hand and by eye until things sync back up.

8. If you can, set up your room tone, Foley, and music before editing.

Before you go any farther, set up room tone for each scene. Also, perform or import any Foley you need, then time it with the action in your film. Lastly, put temp music wherever the director has indicated music will be present. If the director is still waiting on music, don’t work without some sort of placeholder: this is vitally important. Make sure you run the music by the director, of course, but use it all the same.

Why is getting the room tone, Foley, and music a necessity before editing? To save yourself from wasting time.

If you solo a microphone, you may find the dialogue exhibits too much background noise. You’d then de-noise the heck out of it. But if you listen with room tone, Foley, and music, you may find there’s no need to de-noise—the background audio might hide the noise already!

You never want to waste time in post production, so make it easy for yourself to work efficiently. Think of all the time you’ll save, not to mention the audio quality you’d preserve, just by having all the information at hand before making an editing decision.

Now, what is Foley? Foley comprises all the background action sounds that sell the scene: footsteps, cloth rustle, impact sounds, anything that makes a scene more believable. Traditional Foley is bespoke: you record it for the exact scene that demands it.

You may want to record Foley yourself, and here are some tips for how to do that. Alternatively, you could purchase a sound library. I was lucky enough to be supplied with a few sound libraries to review, sound libraries that have tons of room tones and Foley. Most of the time, I go with these sound libraries, unless it’s easier to do it myself or I want something bespoke, and have been given the time and money to produce it.

9. Make your de-noising/editing pass its own affair.

Even with all your elements in place, you may have to de-noise dialogue tracks, especially if they’re going to be compressed later on—compression often brings up the background noise.

For expediency, you’ll want to go with inline processing, using the tips in this article to make sure you’re getting the best bang out of your noise-reduction buck.

For best results, offline is usually preferable. It takes more time, but it always sounds better because you have a finer degree of control.

However you work, try to devote an entire, linear pass to clean-up. It will make your mix faster when you take care of this stuff independently, within its own block of time.

Also, make sure to monitor the noise-reduced results in a realistic way: generate a sort of “dummy compressor setting” that brings you up to your final level. Monitor the edited audio with and without this setting to see if everything works. It’s ironic, I know, but you can actually use processing to reveal if you’re using too much processing!

10. Keep balance in mind while mixing.

Go scene by scene, working in chronological order. As with music mixes, a reference track can be of great help. I use sound from The Wire whenever I’m working on anything with a naturalistic vibe; it’s hard to think of a show more naturalistic than that.

The references go a long way, because they help me in preserving a balance. In mixing a scene, everything is about the balance between intelligibility, environment, and a pleasurable experience.

Once one element is out of whack, the whole scene falls apart in terms of believability. If you push the room tone too loud, the scene seems unnaturally noisy. Keep room tone too quiet, and the dialogue pops out weirdly—everything can feel dubbed, even if it isn’t.

The balance continuously changes with the processing you instantiate. Your tools are the same as they are when mixing music—EQ, compression, and reverb/delay—but the relationships seem more apparent and obvious.

Here’s a typical scenario: you process two dialogue tracks, and now they’re too strong against the background ambience. So you push up the room tone, and now it sounds worse: the room tone overwhelms, your mix is noisy, and nothing is particularly believable.

What’s the solution? Try equalizing the room tone in broad strokes rather than boosting the overall level. It’s always a series of small adjustments and re-adjustments to get the scene as polished as possible.

As for the individual moves you might make in a post-production context, you can read this article and this article for a little bit more research.

Conclusion

As you can see by the sheer volume of this article, there’s a lot to consider in the post-production process. But even so, it’s a wonderful and satisfying way to earn a living within the context of audio engineering. Just remember these three things: Keep your workflow organized, keep the balance of things in mind while your mixing, and most importantly, always serve what’s happening on screen.

Your job is to serve the movie, to make it meet its goals. Take the time to serve that purpose to the best of your ability, especially in the medium of short film. Chances are the director who’s hiring for a short film may not have a feature under their belt—but they definitely have one in mind. Do a good job, and the director will come back to you for more work.