9 Tips to Preserve Dynamics without Sacrificing Loudness

Everyone wants a loud mix, but also one that has a healthy dynamic range. In this article, learn tips for achieving a dynamic mix that preserves its loudness.

Unless you’re going for a hi-fi experience, everyone wants a track that sounds, feels, and heck, just is loud. Don’t deny it just because it’s cool to be contrarian: you crave the weightiness of a loud mix.

Getting your mix to be both loud and dynamic—preserving the transient impact and not causing ear-fatigue at every playback level—now that’s the hard part.

In this article, we’re going to give you some tips for achieving a dynamic mix that preserves its loudness.

This article references a previous version of Neutron. Learn about

Neutron 5

1. Set your levels higher at the outset—but don’t use a limiter

In my youth, I’d ask mastering engineers a simple question: “How do the pros get their mixes to sound so loud?” The answer was always the same, and went against everything I learned from books that championed conservatism: “If you want a loud mix, you have to mix loud.”

What does it practically mean to "mix loud"? To be sure, it’s dependent on many factors—how the song is arranged, how we take advantage of our ear’s innate sensitivities to certain frequency ranges, etc.

But it can also involve a dance with the devil: a mix often seems loud because it is loud.

In these articles, we’ve often advised mixing around -21 LU, and Neutron 3 is set up to give you a mix that hovers around that mark. But I’ll level with you, when I’m asked to deliver a loud mix, I aim higher (-16 LU short term, sometimes as high as -14 LU).

I don’t do this into a limiter. I want to hear my transients in all their glory. And yes, I may get the occasional red light on my static mix at the initial stages of this process. But after I set up my initial balances—when EQ and compression come into play—I carefully engineer things so as not to hit 0 dBFS at the master fader.

Maybe I lower all the faders a bit to compromise. The mix may be a dB quieter overall, but we won’t pass 0 dBFS. If a stray kick or bass hit still triggers an over (passing 0 dBFS) here or there, automating the element’s output trim in a channel strip like Neutron 3, or clip-gaining it down can do the trick—although I rarely automate a fader at this stage; I prefer not to lock them in.

By all means, use a limiter when the time comes—but don’t do it now. Mixing like this can certainly be dangerous to the end goal, and we advocate for preserving headroom and shooting for lower loudness levels for a reason: there’s less chance of you messing it up for the mastering engineer. But this style does have advantages. For one, it forces you to get the most out of the tools at your disposal without the safety of a limiter. The other advantage is practical, which I’ll illustrate with an anecdote.

I once sat in the room while a famous engineer mixed a song for the band Augustana. I clearly remember how he chose to “protect” his mix from the mastering engineer with this very tactic, as he didn’t like who the label chose for mastering. Years later, when a mastering engineer smashed my mixes for a cast album to high heaven, I understood that famous engineer’s attitude and adopted it in certain circumstances.

Now, if you’re going to go this route, you must be careful. Remember that we don’t want to sacrifice the dynamism at the expense of loudness. But that’s where the rest of these tips come in.

2. Make use of illusory dynamics

I was hipped to this term by Julian King. We were talking about keeping things impactful in a squashed, loud world.

He told me, “The loudness of where we live today means we stomp on everything all the time. It would be nice to work on something that had a lot of dynamic range in it, but compared to the records I made twenty or thirty years ago, there’s so little dynamic range, so you start trying to find ways to create the illusion of dynamic range.”

One method at his disposal is deploying “frequency shifts in the mix—where low and high-frequency elements come in to take over the choruses.” Do it well, and you can make a mix feel louder in the chorus by filling out low and high-end content, even when the overall level doesn’t change much.

Other changes can help secure a perceptually louder chorus. Consider keeping elements narrow in the verses and going wider in the chorus. Likewise, you could make the verses more reverberated and dry up the choruses, which can make the chorus feel more impactful by making drums and instruments sound punchier.

3. Cut extraneous lows to keep the mix punchy

Nothing sucks up headroom like low end—and that’s something you’ve probably heard before. But do you know why low end can do this?

It’s due to a complex interplay between several variables, including the way our ears perceive frequencies across the spectrum at different levels, the technology of sonic reproduction, and how low end tends to behave in a mix.

First, because of the way low-end frequencies propagate, they exhibit longer frequency wavelengths. They take more time to die off than their higher-pitched counterparts.

This is exacerbated by the fact that we tend to arrange low-end elements to sustain (e.g. a booming 808). Even in low-end elements that have midrange components (like the pick attack of an electric bass or the knock and click of a kick), that midrange component is often transient and dwindles quickly.

Our ears are also less sensitive to low-end frequencies, so they usually need to be louder for a mix to sound balanced. As a result, lows are usually the loudest frequencies in a mix.

Now consider a brickwall limiter. The limiter is essentially a compressor, which identifies a sound above the threshold and clamps down upon it, doing so in accordance with its time constants (attack and release).

Because the wavelengths of the low end are drastically longer and sustain for a greater length of time—and because lows are likely the loudest frequencies and therefore cross the threshold more than others—a limiter may flag the bass as the continual troublemaker, while the speedier high-mid transient is dispatched and dealt with more quickly. Limiting in the mids may, as a result, feel more transparent than it would in the lows.

Here is a mix in which EQ hasn’t been touched—we’ve only set up the static balances as per the first tip, printing the mix at a target of -16 LU.

Here it is pushed into a limiter until the mix hits -8 LU—on the conservative end of old-school competitive loudness standards.

How does that sound to you? Not too good I wager. We’ve lost all punch and I bet extraneous low end has something to do with it. So let’s use some high pass filters—not just on the low-end elements, but on the midrange synths as well. Note that they do, in fact, display unnecessary low end in the frequency analyzer.

High pass filters on low and midrange elements

The more you allow this extraneous low end to exist, the greater the chance of it triggering the limiter. So, we high pass each element, and this is the result.

4. Find the best frequency point for each element and keep it out of the way of the others

While we’re talking about EQ, let’s talk about balance. A balanced mix, with the appropriate density, has a greater chance of sounding loud without sacrificing dynamics.

But first, what is density? It’s tough to describe, but easy to hear. It’s the difference between these two instruments:

And these two:

And to get here, all we did was boost certain frequencies:

Boosting specific frequencies

We fixed the dense mids by boosting important frequencies in each instrument. We look for each element’s strength, and we play to it, being very careful not to overcrowd any particular frequency range. Certain mix elements—not all of them, but key instruments—are assigned to the vital midrange, and others are cleared out.

Why do we avoid overcrowding? Consider what would happen if the main frequencies of instruments of our mix were crowded into the space between 2–3 kHz, which is a particularly sensitive spot for our ears.

We push this high-midrangey sound into a limiter, and what happens?

It sounds terrible, and here’s why: compressors react to the loudest thing when seeking their triggers. With tons of instruments in one range, our limiter is working overtime; it hears something appearing frightfully loud and responds in kind.

But if we play to each element’s strength—the stabby synth’s low midrange, the lead synth’s high 2 or 3 kHz region, and so on—we can balance our mix, putting it together like a jigsaw, each piece fitting into place. We can use the Masking Meter in Neutron 3 to help us, too.

The results of such carving sound like this at our pre-limiter level:

The results, when pushed into the limiter, sound like this:

This is a far harder-hitting sound than before, with much more transient heft, even though the loudness metering gives us similar readings.

5. Use compression for its intended effect(s)

Compressors are primarily designed to restrict dynamic range. Because of their speed controls, they can also shape transients. And because of their unique circuitries or digital algorithms, compressors can also add tonal color.

If you want to preserve dynamic range in your loud mix, you need to use compression to reign in dynamics so they can play well against the inevitable limiter—you have to give the ball some room to bounce! You can’t squeeze the life out of a track, or else it won’t pop.

However, it is not enough to say don’t squeeze the life out of your track. You must also know why you’re employing compression—to what end you’re using the compressor.

If you’re trying to restrict the dynamic range on a macro level, say in a chicken-picking guitar part, use settings that obtain this goal—like increasing the release time to avoid rapid changes in gain reduction that would disturb the effect.

Is shaping a transient your goal? Try a slower attack and a faster release. Or, better yet, give a transient shaper like the one in Neutron a shot, and compensate for any jumps in overall level—it might work more handily for the job.

And if you crave color, consider not using the tool for compression at all: consider driving the lovely input stage into the highest possible threshold, or splitting the difference between the input and output stages, to give you that glorious box tone. When it comes to color compressors, you don’t have to compress to get the flavor, even if that’s the name of the tool on the tin.

6. Use parallel compression to your advantage on tracks

Sure, you may compress a kick sample for transient shaping. But that might cause clipping when pushed too loud, especially if you’ve decided to raise the makeup gain—always an attractive prospect at first.

Instead, give parallel compression a try. You may find you can actually bolster the level quite smoothly because of the nature of parallel compression itself.

When you add a layer of parallel compression, the effect is masked in louder parts and pronounced in quieter moments. The result is a restriction in dynamic range through an opposite tack: you haven’t squashed the louder transients, but beefed up the quieter parts. This can help preserve impact.

Try splitting the difference between traditional insert and parallel compression. Use compression to shape the transients, but don’t touch that makeup gain knob. If anything, bring it down a dB. Then, use parallel compression to subtly restrict the dynamic range, and afterwards, move everything up in level for an impactful sound that’s nonetheless contained.

Even though many plug-ins give you parallel compression on a knob, I’d suggest sending to a parallel bus instead, and doing so pre-fader. I find the balance is easier to achieve this way—and I’m not the only one to note this; his Holiness Bob Katz has remarked on it often. If you’re looking for mistakes to avoid when parallel processing, look no further.

7. Use parallel compression to your advantage on the stereo mix bus itself

So you’ve set up a healthy static mix, taken advantage of illusory dynamics, balanced the frequencies in their best light, and maintained dynamic impact through judicious use of dynamic processes. Now you’re looking at that master bus and you want to get this thing to compete at a louder level—you want to squeeze a couple extra dB out of the mix without the squeeze.

Do you reach for a compressor? Sure, but that may not be your friend where preserving impact is key. Observe our mix, with compression and makeup gain used before a limiter.

Not particularly hard-hitting, is it?

Well here’s something interesting: for the same reasons as our previous tip, parallel compression can give us our boost in loudness without the same strangulation.

Observe this example, where we’ve sent the mix to a parallel bus, one with a compressor sporting these settings.

Compressor settings in Ozone

It hits harder, despite measuring the same on the meters—and that’s what parallel bus compression can do for us.

8. Preserve the transients on a mix-wide level

When comparing your level-matched, limited, and compressed mix to the pre-treated original, you may find that despite all your best efforts, you’re getting an unwanted squashed feeling. Listen specifically to the groove of the song—to the kick and snare—to determine if this is the case.

What are you to do now, when you’re so close to your goal?

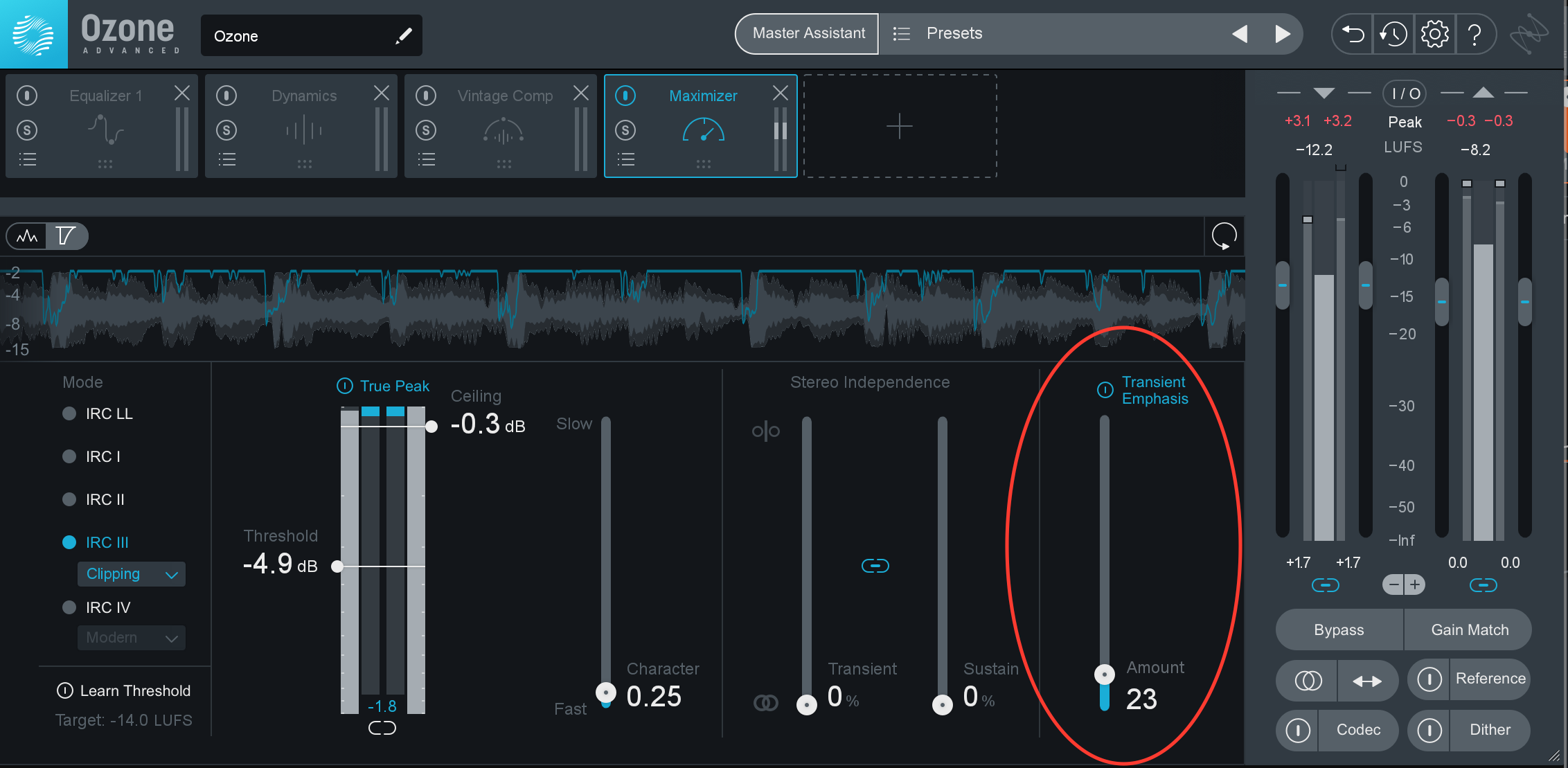

Observe the Transient Emphasis slider on the Maximizer module in Ozone 9.

Transient Emphasis slider highlighted in the Maximizer in Ozone 9

It’s a relatively simple control over a profound operation: the Transient Emphasis slider adds a pronounced sharpening to the transients of a mix before it hits the final limiting stage. Think of it almost like the attack slider of a transient shaper for your whole mix.

Give it a little bump, and you may see it add some of the vitality back to transient material, such as drums. Don’t go overboard though: give yourself a healthy amount, then pull it back untill you no longer feel what it’s doing. Then inch it forward to where you’re just noticing the benefits of the process. Most likely, this is all you need. Observe the difference:

9. Reference against mixes at their level

We often tell you to bring the level of a mastered reference track down to match the level of your mix. And yes, you should do this at the beginning of the process, when you’re thinking about mix elements individually and not worrying about loudness yet.

But when it comes time to match loudness, bring that reference up in level to its normal state and try to match it, pound for pound, as you make your final tweaks.

Conclusion: It’s the little things

Successfully felt loudness is not a matter of pushing something hard into a limiter. It requires a thoughtful approach, some careful planning, and yes, a lot of decisions on a minute level. You’ll notice it’s a bunch of tiny tricks that add up to something big.

Also, one cannot overlook issues of sound selection and instrumental arrangement. Just like how a delicious chili starts with the right chili peppers, instruments chosen for their density, impact, and aggression are a large part of the battle. The arrangement of those instruments—what parts they play, and how they play them—is also vital. If a producer doesn’t give you power to change inferior sounds, and if they aren’t giving you good ingredients at the outset, the point is moot: you’ll rarely get the intended weight and impact of a loud mix.

You see, dynamic loudness is more than a setting on your monitor controller—it’s a state of mind, a way of life. Live it loudly, and live it proudly.