6 Tips for Widening the Stereo Image of a Mix

In this piece, we look at what stereo width is and how you can achieve good stereo imaging in mixing or mastering. From tools to methods, we've got you covered.

There was once a time when mono was king. From radio to record players, most listeners only had mono playback systems. As a result, creating a good mono mix during the record production process was the primary focus. During the 1960s, though, this started to change, and by the time The Beatles released Abbey Road in 1969, the stereo era was in full swing.

These days, most artists and producers want a wide, spacious stereo image. However, achieving this is often easier said than done, especially in a way that measures up to your favorite commercial releases while still offering good mono compatibility. In this article, we’ll look at not only how to achieve good stereo imaging, but also why mono compatibility is still important in 2022, and how the two can coexist.

Jump to these tips:

- Use monitors when manipulating stereo width

- Make sure your stereo imaging decisions don’t hurt your mix in mono

- Use panning techniques

- Make use of phase to widen the stereo image

- Use the Haas effect to widen sounds

- Consider genre and instrumentation

Try these stereo imaging tips with

Ozone Advanced

What is stereo imaging?

Stereo imaging is the process of positioning sounds within the stereo field to create the perception of locality. Building a good stereo image will help your mix sound wider and will give each instrument it's own space in the mix.

How to widen the stereo image

Perhaps the more interesting question though is, “what creates stereo width?” In the broadest sense, the impression of stereo width is caused by differences between the left and right channels. These differences can take many forms, which we’ll explore below. Prime among them are differences in level, phase, panning, timing, or some combination thereof—although additional possibilities also exist.

1. Use monitors when manipulating stereo width

You may naturally wonder what monitoring has to do with achieving good stereo width. However, when you consider that your stereo-related mix decisions will be impacted by the way your monitoring system conveys imaging to you, the reasons may become clearer. The main thing to consider is whether you’re mixing on speakers or headphones.

In general, stereo imaging—and thus width—tends to be easier to get right on speakers. A mix that is created to have imaging that sounds good on speakers is more likely to translate well to headphones than vice versa. This is largely due to a phenomenon known as crossfeed. Crossfeed is what occurs when a sound originating from your right makes its way into not only your right ear but also your left.

For example, if you pan something hard right and listen to it on speakers, the direct sound will first arrive at your right ear, and then, no more than a few hundred microseconds later, at your left ear. In addition to this minuscule but important time difference, the presence of your head and face will physically attenuate some of the higher frequencies by the time they get to your left ear. These spectral and timing differences are a big part of what give us cues about sound localization in the natural world.

In contrast, on headphones, a hard-panned right sound will go directly—and exclusively—into your right ear. The lack of crossfeed—or signal in your left ear—is part of what makes hard-panned sounds feel rather unnatural on headphones. As a result, there is a tendency to temper your panning and imaging decisions while working on headphones which can ultimately lead to a narrow mix.

That said, there are tools to simulate crossfeed which can make imaging decisions in headphones easier. Using headphones, take a listen to the following excerpt of “Bring Me the Moon,” by Iris Lune, first flat, and then with crossfeed simulation by Goodhertz CanOpener Studio.

Flat vs. Crossfeed Simulation

For me, adding crossfeed not only makes the hard-panned elements feel more genuinely wide, it also makes the center feel more focused and creates a smoother transition between centered and panned elements. It’s no substitute for a good speaker-based setup, but if headphones are your only option, it sure helps!

One additional consideration is that when working on speakers, a little acoustic treatment can go a long way. If you treat nothing else, placing absorbers at the first reflection points can yield enormous improvements when it comes to stereo imaging and the ability to accurately locate sounds in the stereo field.

2. Make sure your stereo imaging decisions don’t hurt your mix in mono

There is one basic principle to be conscientious of while mixing in stereo: when a stereo mix is collapsed to mono, panned elements get quieter. In other words, summing to mono changes your mix balances between centered and wide elements. However, if you’re mindful of this, you can use it to your advantage to make sure the important elements in your mix still stand out in mono.

This may seem counterintuitive, but the specific ways in which we make things stereo and achieve width has an impact on how they will ultimately sound in mono. In case I need to convince you that mono is still important in 2022, consider the following.

From smart speakers to club sound systems, and phones to background music systems in retail spaces, there are still plenty of mono playback systems out in the wild. While you might be tempted to write at least some of these off as a lowest common denominator, I would still argue that having a mix which holds up well in mono is important for listeners whose first exposure to your music might be on one of these systems.

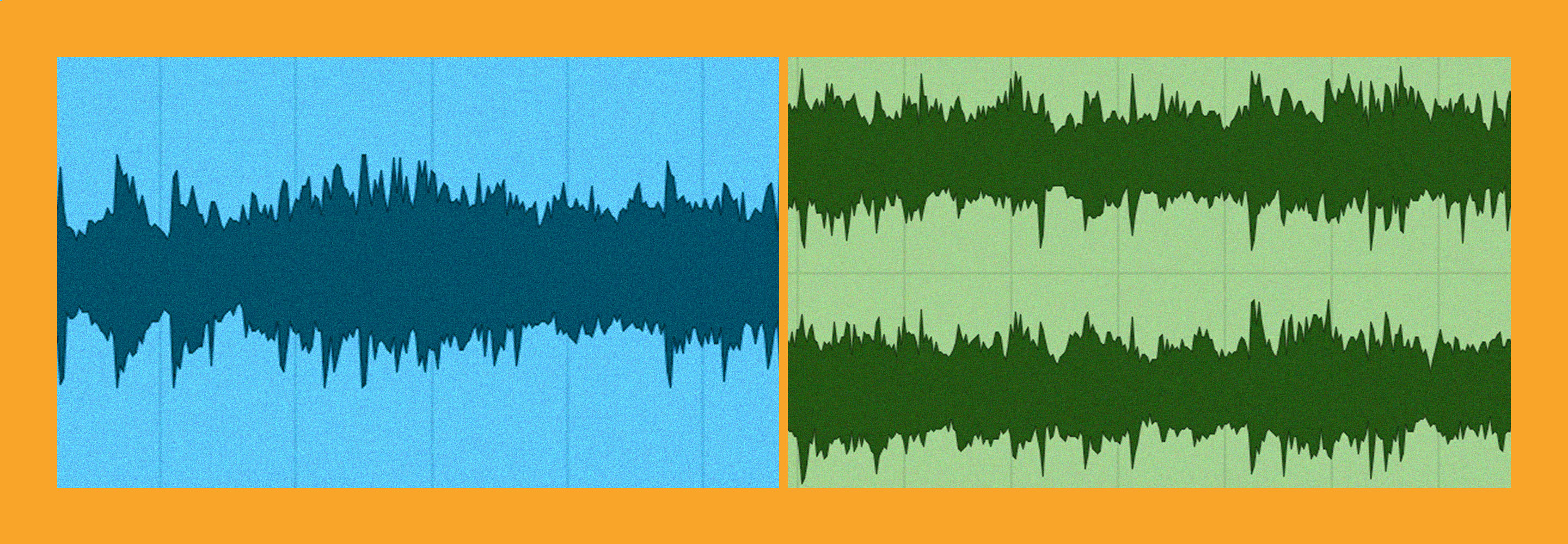

We’ll get into the specifics of this when we discuss different techniques below, and see that different techniques of stereoization yield different results in mono. For now, check out the differences between the stereo and mono versions of our “Bring Me the Moon” excerpt.

Stereo vs. Mono Mix

Not exactly subtle, eh?!

3. Use panning techniques to get a wide sound

One of the first and most obvious ways most people learn to adjust imaging and create width is through the use of panning. While the basics of this are certainly simple enough—use the panner to position individual elements anywhere between hard left and hard right—there are some nuances and subtleties that we can take advantage of.

First, consider mono compatibility. As previously mentioned, panned elements will end up quieter in the mono downmix. Specifically, hard panned sounds become about 3–6 dB lower in level when collapsed to mono. We can use this to our advantage though. By keeping the important, focal elements of the mix—lead vocals, kick and snare, bass, etc.—at or very near the center, we can ensure that their relative levels remain consistent when summed to mono.

Conversely, by moving elements which fall into the ear candy or background categories to the edges of the stereo field, we can ensure that they don’t overpower the focal elements when summed to mono. This is especially important since frequency masking is more prominent when two sounds share the same location. Of course, we’re not limited to centered or hard panned positioning, and by using the full stereo field we can sculpt balances that work well in both mono and stereo.

It might seem like that’s about all there is to consider with panning, but before we get into any of the phase or delay tricks, I have a few additional panning-related tips for you.

- Contrast: Just as contrast can help with dynamics and mix depth, the same is true for width. Consider reserving the widest positions for elements which only come in during musical climaxes. You could even automate the pan positions so they get a little wider with each subsequent chorus, for example. This will help the width really stand out when it comes in!

- Dry vs. wet pan: Stereo effects like reverbs and delays certainly have their place, but don’t write off the effectiveness of a mono reverb or delay. By controlling the position of the effect relative to its source, you can achieve powerful things. For example, panning an effect wider than the source means the wet/dry balance will be drier in mono, while spreading the sound out slightly in stereo. Further, whether you pan the effect to the same or opposite side as the source will impact that sound’s total apparent width in the stereo mix.

By way of example, here’s a guitar from SESSION GUITARIST by Native Instruments with reverb from Neoverb. Both have been set to mono, and the guitar panned 50% left. During the first 16 bars, keep an eye on the pan position of the reverb, and check out how it impacts the overall imaging. During the last 16 bars, when summed to mono, notice how the reverb comes up in the mix when panned center.

4. Make use of phase to widen the stereo image

We’ve talked about what phase is and how we can manipulate it previously, and now it’s time to look at how we can put it to work in our mixes to impact stereo width and imaging. Because of how sensitive our ears are to phase difference between channels, we can use it to spread a sound out and increase its apparent size. If we’re careful, we can even do this without taking a level hit in mono!

Specifically, if we keep the phase shift between left and right to about 90 degrees or less, we can achieve a wide stereo image for a sound, while keeping the level almost identical in stereo and mono. There are a few ways to do this. If we want to apply a precise phase shift to all frequencies, we could use the phase module in

RX 11 Advanced

If that feels too overt, a subtler effect can be achieved by using a stereo high pass filter with subtly different settings in the right and left channels. Here’s that same guitar switching between mono and stereo every 4 bars, this time using the HPF technique via

Ozone Advanced

Of course, we couldn’t very well have a discussion about imaging and not mention Ozone Imager, could we? Whether you’re using the free version, or the Imager module in Ozone, you have a number of options at your disposal to affect the positioning and overall width of your sounds. While Imager is great to enhance or control the width of stereo sounds, don’t discount how useful it can be on mono sounds as well!

Pushing beyond the speakers with Imager

For example, by pushing the width slider up slightly, you can take a hard-panned sound and push it beyond the edges of the stereo field, or “outside the speakers.” This is a neat trick, but use it in moderation and don’t forget the impact it will have in mono: sounds manipulated in this way will be even quieter in mono than if they were simply hard panned.

Imager’s Stereoize feature is another great way to add size and width to a mono sound while maintaining mono compatibility. Experimentation is key here. Don’t be afraid to try both mode I and II, tweaking the character slider in both. When using this on a mono sound, the width slider controls the total width of the stereo signal added. In other words, keeping it at 0 will leave the sound mono.

5. Use the Haas effect to widen sounds

Lastly, I’d like to look at some tips you can use if you decide to employ the Haas effect. The Haas effect is a powerful way to pan and widen sounds, but it can easily lead to comb-filtering in mono. However, there are a few things we can do to ensure that the tonal and amplitude effects of the comb filtering are minimized.

As a refresher, the Hass effect is a technique in which you pan the dry sound to one side and a slightly delayed version of the sound—without any feedback—to the other. By “slightly delayed” we mean in the 0–30 millisecond range. It is this very short delay between the two that can lead to severe comb filtering in mono. So what can we do to minimize this?

First, try tuning the delay in mono. This will allow you to hear the comb filtering in all its glory and find a setting which is least offensive for that particular sound. Second, turn down the delayed signal. Even 3–6 dB of attenuation can significantly reduce the severity of comb filtering in mono while retaining the added width in stereo.

Third, keep in mind that the dry signal doesn’t have to be hard panned for this technique to be effective. By panning the dry portion in slightly you can increase the level difference in mono—remember, the hard panned delay will lose more level than the partially panned dry signal—further reducing comb filtering. Lastly, try high and low pass filtering the delayed signal. The combination of phase shift and attenuation from the filers will also help minimize comb filtering.

Here’s an example using all those techniques. The first 16 bars are in stereo, with the Haas delay turning on and off every two bars, while the last 16 bars are in mono, with the Haas delaying turning on and off in the same pattern.

Can you tell when it turns on and off during the mono section? The comb filtering is certainly still there, but it’s much subtler than it would be using a simple Haas delay, and in a full mix it could likely escape detection altogether. For comparison, here’s a simple Haas delay turning on and off in mono.

6. Consider genre and instrumentation

No matter which of the above techniques you choose to employ, it’s important to consider factors like genre and instrumentation while creating the imaging for your song.

Genre not only informs stylistic choices about how much and what types of imaging and width are appropriate, but also what types of playback systems the song is likely to encounter. For example, if you’re mixing electronic music played in clubs, having a good mono mix is arguably more important than stereo. Even if a club sound system isn’t mono, the vast majority of clubgoers will only hear the sound from one speaker at a time.

Furthermore, while ultra-wide ear candy might make sense on a pop mix, it could sound totally out of place in a folk or traditional jazz recording. Bear these factors in mind when making imaging choices.

Lastly, instrumentation should also play a role in your imaging decisions. While low frequency width can be an interesting effect, it doesn’t translate well on all systems, so in general things like basses and kick drums tend to do better up the middle. Instrumentation should also factor into our consideration of the mono downmix, so instruments and voices which play an important role likely don’t want to be too wide.

Putting it all together

Stereo imaging and width are vast topics, and believe it or not these tips are really just a jumping-off point. Building a spacious, convincing image that translates well to mono is a skill that can take years to master, so don’t be discouraged if it doesn’t happen right away. You could easily expand upon and experiment with all of the topics presented here, but they provide a solid foundation for you to build upon.

So next time you fire up your DAW to start a mix, try to make a point of incorporating one or two of the tips outlined above. As certain ones become second nature, it will get easier to incorporate others without feeling overwhelmed and before you know it you’ll be building big, wide mixes that stand up to your references.

Ozone Advanced