2 Approaches to Mixing Live Drums

Sometimes, drums are recorded quite badly, or out of step with the rest of the tune. It’s your job to fix it. Here are two common approaches to mixing live drums.

I am quite happy to bring you this article, long as it is, because I believe that mixing drums speaks to the very core of who we are as engineers. Indeed, speak to a fellow in the trenches of drum mixing, and you’ll hear this person identify with a particular technique as one might identify with a political party.

And, as it sometimes goes with politics, we can forget why we subscribed to a particular way of mixing drums in the first place. That’s why I thought it would be beneficial to break down two techniques for mixing live drums, delving deeply into their steps, but also cover why we might employ one over the other.

The aim here is to help you handle any drums that come at you; sometimes, drums are recorded quite badly, or out of step with the rest of the tune. It’s your job to fix it, so familiarizing yourself with multiple techniques can help you get out of specific binds.

This article references a previous version of Neutron. Learn about

Neutron 5

We shall begin to cover our methods momentarily, but first:

What both techniques have in common

Before anything else, we ought to give a listen to the rough mix and envision the end result. This will govern our drum choices, including how wide our drums will be, and their relative impact within the song.

Also, before mixing in earnest, it behooves us to do a polarity check between microphones (or groups of microphones). We want to make sure the kit sounds its best by choosing the appropriate relationship between each element. Start by panning your overheads hard left and hard right and flipping the phase on one channel. Focus on the kick and snare you do this: do they sound palpably better in of the inversions? Is there more meat in the snare, more heft to the kick? Now observe the stereo field: is there more or less focus? The difference should be glaringly obvious.

Once this is sorted, test more polarity relationships: put the kick against overheads, then snare against overheads, then snare top against snare bottom (ditto “kick in” against “kick out,” and subkick against other kicks, if these are offered), hats against overheads, toms against overheads, and room mic and against overheads. We do this to build the most cohesive sound we can, looking for fullness, roundness, and no obvious loss in frequency ranges.

Soon your ears will tell you instantaneously what is right, but if you’re having trouble distinguishing the best sound at first, here’s a tip:

Set up an easy-to-read meter on the output of the session; something like iZotope Insight will do the trick. Solo the elements you’re checking (say kick against overheads) and watch the meter over a period of four bars. Flip the polarity of the element in question (the kick, for argument’s sake), and see which configuration gives you the louder reading; usually, the more in-phase alignment will yield a louder result. It may not yield the better result, but it may indicate which one is technically correct.

But also consider that technically correct might not be the best kind of correct, as Michael Stavrou is quick to point out: sometimes character comes from the lesser of two choices. Still, when you’re just learning, seek out the more in-phase choice; learn the rules before you’re confident enough to break them.

Once polarity is sorted, we can move on to our various methods.

1. The outside-in drum mixing method

In this method, we move from the overheads out to the close mics. This technique works great for big, naturalistic drums recorded in roomy environs—where the leakage between mics sounds great, and gating doesn’t usually enter into the picture. For a rock, jazz, or acoustic sound that lives and breathes, this is the method to try. The one drawback is that you live or die by the quality of your overheads—the rest of your drums will fall behind them. So if you’re working against an overhead sound you don’t like, this technique might not be best. It also might not be suitable for an overly dense mix with electronic percussion—one in need of an up front drum sound.

Overheads: With our goals for the mix firmly in mind, play with the panning of the overhead tracks, using the technique outlined in this article to answer questions such as, do we want a centered snare? Or does that not matter, considering the rest of the arrangement? Maybe mono is the answer?

Only after establishing this picture do I listen for tonal peculiarities. Is there a harshness in the cymbals? Is there low end rumble I won’t need? I can do minimal EQ adjustments here, not to the left or the right mic, but to both together, as I’ve routed their outputs to a stereo aux track.

Indeed, I find it best to treat the overheads as a single, stereo sound. You may hear issues in the right channel not prevalent in the left, and this may call for individual EQ later on, but for the majority of your decisions, try to look at the overheads as a single picture, so you make uniform decisions that don’t throw one mic out of whack with the other.

Next I secure a good level for the overheads, balancing them against other instruments in our mix—the bass, the harmonic instruments, the vocals. Set about getting a cursory balance between these elements, looking for clarity and suitable impact, and then move on.

Room Mics: Up next is the room mic (though sometimes you get two). The room provides our first means of applying dimensions to the overheads, so we bring it up against the overheads until it’s adding something to the sound—not drawing obvious attention away from the overheads, but complementing them.

Now consider what, exactly, are we adding here? Is the room mic detracting in some frequency range? Address this with EQ if you’d like. Do the room mics need a bit of help in adding perspective? If so, we can try compression, often in extreme measures. With a slower release and a low threshold, you can even out every bit of the drums and the room they occupy. It won’t sound natural, nor will transients be the primary concern—a pancake-flat affect is okay if it’s bringing out the space between each hit, giving the rooms that Led Zeppelin feel.

Note that the room mic might not need compression. It depends on the variables of the song, which is why we had you listen to the rough before beginning.

Perhaps the room mic is not providing the depth you like, and is a bit too dry. You have two choices here: you can abandon the use of a room mic as a depth-perceiver and turn it into a timbre agent; or you can sweeten the ambience of the room with modest reverbs and delays.

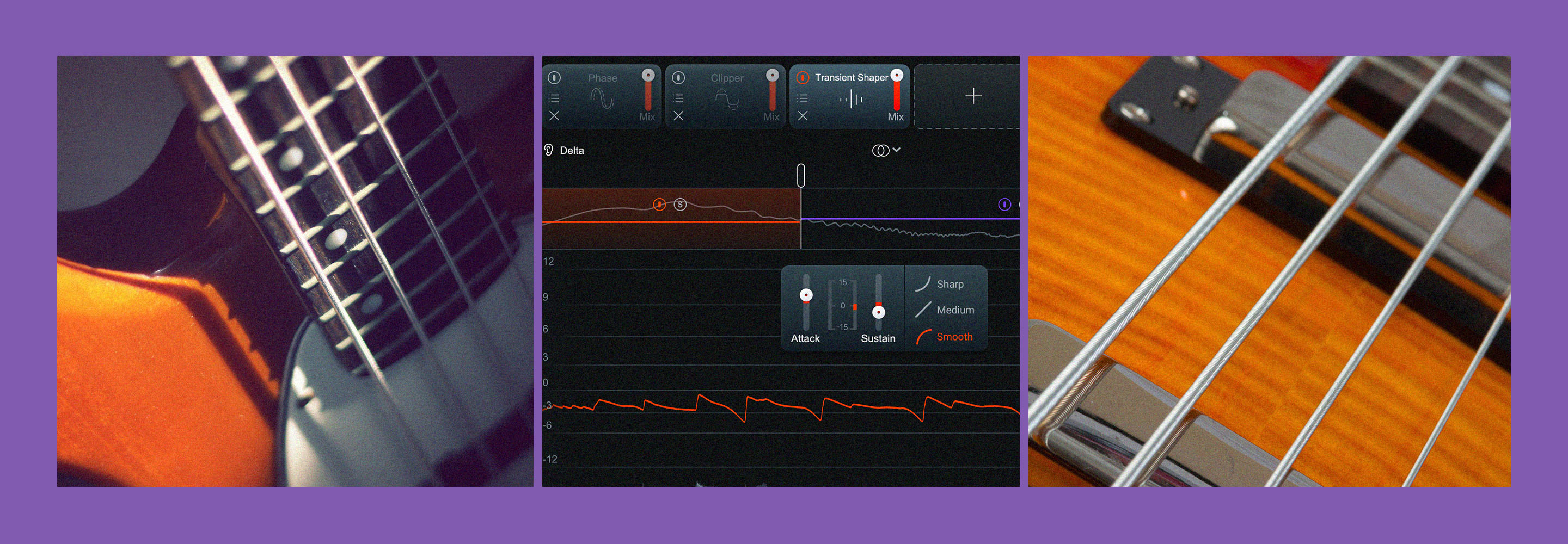

In the former case, the world is your oyster with distortion, EQ, compression, and transient shaping—in short, grab something like Neutron 2 and go hog-wild until you’ve got a cool, signature sound that fits within the context of the mix.

If you’re going the other route, be subtle in your use of reverb. Choose an appropriate plug-in, favor early reflections, and leave the mix relatively dry. With delays, remember that in-time echoes add perception, whereas out-of-time delays add distinction; we want perception, not identification in this case.

You may find, at this point, that the room mics are overwhelming the picture. Go ahead and rebalance them. In fact, rebalance elements against the overheads constantly as you’re building the kit.

Kick and Snare: Keeping the overheads and room mics in, I usually work on the snare now, bringing it up in level. If I notice a strong papery sound that I don’t like—or a ring that needs dulling—I’ll take care of it with minimal EQ.

Next I bring up the under-snare mic, if it exists, already polarity-checked as outlined above (I’ll want it to add crispness without taking away body, and one polarity setting will usually beat the other).

I use the bottom snare for high-end crispness on the hardest snare hits, so I bring it up in volume to a suitable point, high-pass it a little, and make sure that when the snare really hits, we get a crispy sound from the under-mic. Sometimes I’ll gate the chain so it only plays on the hardest hits.

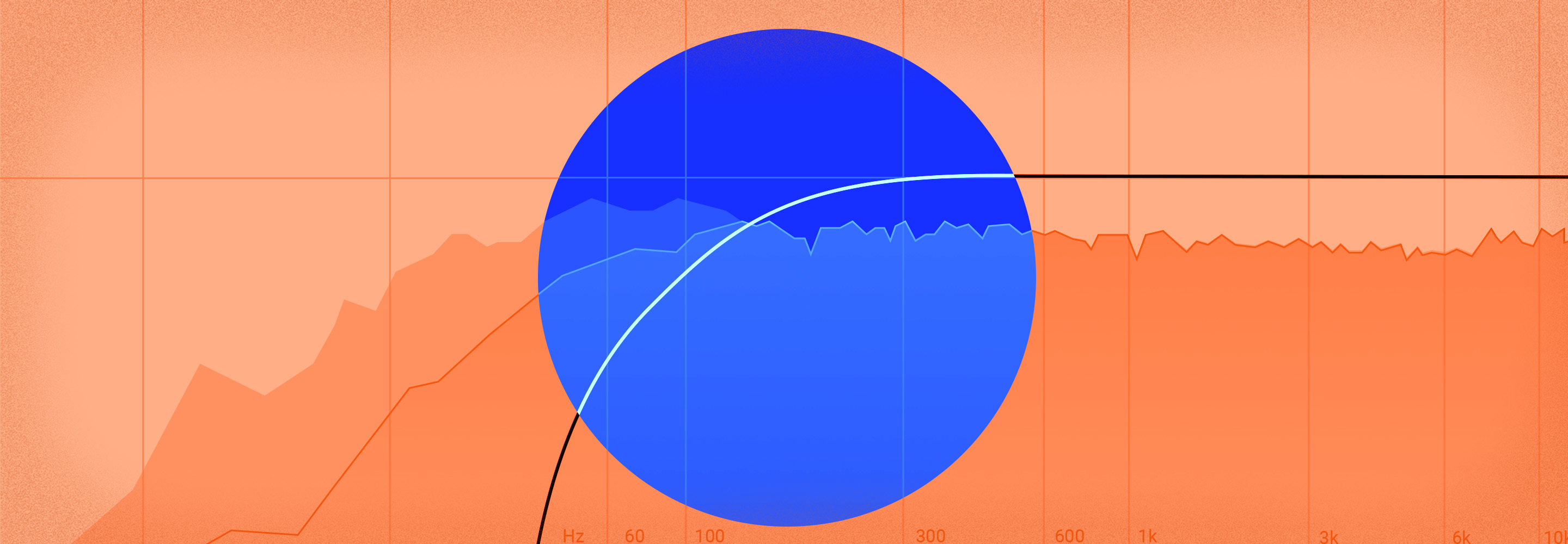

Now I move on to the kick mics. For just a moment, I’ll solo the fullest kick and the bass instrument, looking for overlapping frequencies, and making the decision of who occupies the lowest of the lows. When this question is answered, I notch down the overlapping frequency range either from the kick or the bass (Neutron 2’s Masking Meter can be a good help for), and unsolo everything. If multiple kick mics are offered, I bring them in here and balance them.

We’ve now got kick, snare, overheads, rooms, and bass, all at full volume. Music and vocals probably dwell a little lower.

Presently I make decisions for compression and EQ on the kick and snare, and these vary from song to song. On snare, I like to boost whatever low-midrange frequency I can get away with to give heft without interfering with everything else; on kick, I like to emphasize the click of the kick—the 2–4 kHz region that gives it some snap—and perhaps boost the low end. The use of compression here is entirely up to your tastes and the songs needs.

Hats:

You may have a hi-hat mic. You may not. If you do, pan it to where it lives in the overheads, lest your hat sound blurry and unfocused. Now listen for snare bleed. If there’s too much, the snare might skew from center on strong hits.

You can sidechain the hi-hat to the snare, so it ducks whenever the snare hits, or you can go through the hat track, separate by region, and mute obvious snare hits. The former takes less time, but may result in more tweaking down the line. It will also change the entire groove of the drum kit, which may or may not be desirable.

The latter takes loads of time but allows you to exert a fine amount of control right at the beginning.

Toms:

For the toms, you could choose to use the tips offered in this article (insert macgyver). Do make sure, though, to pan the toms to match the overheads, especially if they’re part of the beat (rather than just fill material).

The great benefit of the outside-in method is how the overheads paint our general picture—so toms will already be in the overhead capture. In this method, you can use the close mics to provide heft, emphasis, and incision for specific moments.

If you find yourself piling heaps of EQ in one area and drastic cuts in another, don’t be alarmed; that can be part of the process. With toms, it’s usually a ton of EQ or barely any at all; some high-pass filtering usually comes into play, but then the rules sort of fly out the window as you struggle to make it feel like the record you want to hear in your head. All of this is to say, don’t judge yourself for how you get to your tom sound—some of the biggest engineers struggle with it.

You can use compression to emphasize transient attack, rather than to even out of dynamics. An exception, though, should be made for an inconsistent player keeping time on the low-tom as one would play the hi-hat or ride. Here you ought to apply compression for dynamic control rather than emphasis. Sometimes sidechaining the low-toms to the snare or kick can help tom patterns feel rhythmically alive, yet consistent.

The one secret bit of sauce I can give you, when it comes to toms, involves reverb, and you can read about it here.

2. The inside-out drum mixing method

This technique is almost the complete reverse of the other process: we build the picture of the drums from the kick out to the room. Why do we do this?

For mixes where the drums need to sound more synthetic—or need to blend with synthetic elements of percussion—the inside-out technique goes a long way. Likewise, the inside out technique works well when you don’t like the sound of your overheads, whether they sound cheap or just not what you want.

In these scenarios, the inside-out method gives you a greater degree of control in how you build the drums, more freedom to carve out the sound you want. Just don’t think it’s going to sound as natural as the other technique; it’ll usually sound more manufactured and closed-off, but this can be a virtue if the song calls for it.

Kick:

In this method, I start with the kick and bass playing off each other, looking for the frequency overlaps and choose a winner for the low end. It’s a bit like the other method at first. But once I’ve made a decision, I work with the kick drum mic(s) to get everything I need, almost from the get go. It’s a much more precise picture, with much more processing applied, and at an earlier point in the mix.

I tend to start with gating. I don’t want extraneous sound from the rest of the kit in here—just the kick, please. I play with attack, release, threshold, and hysteresis to get the kick isolated. If you’re using something like Neutron 2, you can use the the track assistant to get in the ballpark and tweak from there.

After gating comes equalization and compression. Try to work on these two at relatively the same time, because they’ll influence each other. Try to emphasize the good lows, take out the midrange frequency you don’t like, and give the kick some snap to cut through the mix.

Compression can even out an inconsistent player, or give more heft to the transients. If this transient heft is untenable because the player is too inconsistent, use compression to even things out and then emphasize the transients with a transient shaper. All of this can be done with Neutron.

It’s not uncommon to see the following: a boost at 60 Hz, a notch at 500 Hz, and a boost at 2 kHz. It won’t be those numbers every time—and the bass changes everything, of course—but that’s not a bad place to start. Sometimes you also find yourself emphasizing frequencies between 100–200 Hz, but this is only if you want the kick drum to really “knock”, and only if the bass allows for it.

If you have multiple kick mics, start with the one providing most of meaty information and go from there. Always check for polarity issues between the mics and pick the arrangement that gives you the most thump and attack from the kick.

Snare:

Again, with the music in place, bring the snare up and do what you did for the kick: gate, equalize and compress, and then use transient shaping if need be. You won’t be getting the meat of your sound from the overheads. Instead, the close mic is your beacon in the snare-darkness, so you must work judiciously to eliminate unwanted ring, unhelpful papery sounds, and nasty high-end harshness. As with the kick, compress for transient emphasis—or compress for dynamic consistency if the player is all over the place. Perhaps play with the release stage of the transient shaper to bring out more of the lingering tones, though a little attack might help to. When it comes to EQ, emphasize frequencies that bolster the heft of the instrument, as well as its “crack”. I find these often exist between 120–250 Hz, and again at 4–6 kHz. So that’s a good starting point.

Treat the bottom snare mic as you did in the outside-in method.

You may, if you wish, apply reverb to the snare at this stage, if the ambience is meant to be a part of the snare, rather than an accent to help it blend into the room.

Hats:

Here, use compression for evenness if the player is inconsistent, or side chain to the snare if there’s too much bleed. Don’t go crazy on EQ: usually a bit of high-pass filtering and a wide notch to tame anything overly harsh is all you need. Find a level that works with the kick and snare, as well as the harmonic instruments, and move on to your overheads. You can choose to pan the hats with your overheads, but you might not need to: if they’re quiet enough, you can put them in a variety of places; if the snare bleed is too heavy, you can put them up the middle and make it a part of your snare sound.

Overheads:

Pick a section with a few cymbal hits, so you can work on the blend of the overheads and the spot mics here. You can use compression to emphasize attack or minimize sustain (if that’s an issue). Be sure to watch out for pumping, though, because that will sound unnatural, and usually bad.

For EQ, you’ll find yourself taking out nasty harsh frequencies as you did in the outside in method (I find the 4 kHz range can often be a culprit), but also, you may find yourself filtering out low frequencies to make room for the close mics, so that your kick, snare, and hat may dominate this part of the picture.

As your close mics are doing more of the work, you can use the overheads to lesser degrees, which allows you to make more drastic EQ cuts if need be. Many times I’ve gotten around a cheap-sounding overhead capture by relying on this method, putting the overheads just loud enough to hear the crash and ride cymbals. In especially dense mixes, you can get away with this, and no one’s the wiser.

Room:

This technique usually engenders an in-your-face sound to begin with. So the room may function better as a character indicator, distorted and compressed to high heaven, rather than as a perceptive indicator. Both are valid—it just depends on the song. Your moves are similar to what they were in the other technique, except now your balancing the room against the rest of the kit.

Toms:

I save the toms for last again, snaking around to finish them up. The approach on the toms will be similar to the outside-in approach, with one main difference: the close-mics here are your primary source of tone, as you’re relying on your overheads only to fill out the sonic picture. This gives you more opportunity for control, but don’t be surprised if you spend a lot of time filtering out unnecessary low end boom, emphasizing the fundamental, and taking out midrange boxiness while adding snap. If the toms need compression, apply similar compression the whole way round so that they sound congruent. The reverb trick outlined previously has also benefited me in this method.

Now what?

No, you’re not done. Now the real fun begins, no matter the method you started with. With everything in place you can begin to make minute adjustments:

Is there too much midrange from the snare? Let’s get to it. Is there too much harshness coming from the cymbals? Time to mute the rooms and see to see if it’s coming from the overhead mics. Shall we add sample augmentation? If so, now’s the time.

This is where I begin sculpting in earnest, always making sure that what I’m doing is in service of the cohesive instrument that is now the drums—and always making choices in reference to the whole mix. Parallel compression, reverb, all of the bells and whistles can now be applied to further the goal of your drums.

Conclusion

These are but two ways to mix drums. There are many methods, and you’ll find hybrid techniques too. Some engineers work with all the drums in, all the time, and pare down to the sound they want. Others work in frequency pairings—kick with bass, snare with vocal, toms with guitar, and so on. Some form amalgams that work for them, taking what they want from each method.

The point is to know the benefits of a given technique, so that you can drum up the most appropriate sounding mix. Without proper knowledge, you can get yourself caught in the snares, and wind up kicking yourself for not seeing the dangers overhead.

And again, please forgive the puns.