What Is the Difference Between Mixing and Mastering?

What’s the difference between mixing and mastering? We look at the differences between the two disciplines, and why they are important to the music you make and listen to.

If you're not a mixing or mastering engineer, you probably have questions about how the two processes differ. The technical talk and knowledge of gear leave even the most experienced musicians feeling confused, so that outside of the engineers themselves, few people really know what happens during these final stages.

And this mystery leads to lots of misinformation—some people consider the two processes one and the same, or discard them as unnecessary if the music composition is good to start.

To pull back the curtain, we’ll look at five key differences between the two phases and offer insight into why they are important to the music you make and listen to.

First, we’ll start with a broad and simple overview of both disciplines. Then we’ll move on to granular differences when it comes to workflow, perspectives and tools.

In this article you’ll learn:

- The difference between mixing and mastering

- What a mixed and a mastered song sound like

- The distinctions between mixing and mastering workflow

- The tools mixing and mastering engineers use

What’s the difference between mixing and mastering?

Mixing is the stage after recording where you blend individual tracks together, while mastering is the the final stage of audio production where you polish the entire mix to prepare for distribution. Mixing is when an engineer carves and balances the separate tracks in a session to sound good when played together. While mastering a song means putting the finishing touches on a track by enhancing the overall sound, creating consistency across the album, and preparing it for distribution.

To put it another way, here’s an analogy in terms of books: The artist is the author. The mixing engineer is the editor, helping the author frame their project in the best light. The mastering engineer is the copyeditor, minding the Ps and Qs. So what do they really do in a musical context? Let’s break down each part separately.

What is mixing?

Let’s start at the beginning. You laid down some rhythm parts, you made some music, and you sang a few choice words: you (or your band) produced an arrangement, and now it’s time to make that arrangement feel like a song, rather than a loose affiliation of parts and tracks.

This is where the mixing engineer comes in. It’s their job to balance all the tracks and do whatever it takes to make them feel like a solid, cohesive song. With tools like EQ, compression, panning, and reverb at their disposal, mix engineers reduce clashes between instruments, tighten grooves, and emphasize important song elements. In some cases, they might even layer drum hits with samples from outside the session or mute redundant instrument parts.

Mix engineers EQ instruments to shine over other instruments, or to fit into the right context. They compress individual tracks to reign them in, or to punch them up. They add all sorts of crazy effects when necessary—reverb, delay, modulation, pitch fx, anything that serves the material.

This transitions us to a mix engineer’s second function: to serve the emotional impact of the song—to bring it to life. You give them three to 200 tracks of material, and they give you a cohesive song.

What is mastering?

A mastering engineer is your last line of defense before your song, single, EP, album, or mixtape hits the world. They are the QC—the quality control—and their job boils down to tasks best delineated in contrast to mix engineers.

A mixing engineer balances ten, twenty, or upwards of a hundred tracks into a single song, one that sounds great in their studio. Mastering engineers predominantly work with a singlestereo track (before sequencing and metadata tagging), and they do everything in their power to make this track shine on every conceivable playback system.

This doesn’t mean simply slapping an EQ, a compressor, and a limiter across a stereo track and making it as loud as possible–though mastering engineers do use these three tools.

Their goal is often translational and relational: they want to make each song fit with every other song in the project. They also aim to make your entire project compete with (and hopefully trounce) similar material by established artists in the genre.

They want to make sure this competitive edge holds on every single playback media under the sun, as best they can–and often, they do their best to make the result timeless, both in terms of sonics (a song that will stand the test of time in tone), and file delivery (giving you everything you need going forward to re-release your project as the media landscape changes).

The tools to accomplish this go beyond EQ, compression, and limiting. In a mastering context, the room they master in is arguably one of the most important tools, helping the mastering engineer catch any potential problems and fix them on the spot.

The speakers, in conjunction with the room, are also vital: a mixing engineer often does just fine with a pair of NS10s. A mastering engineer will likely utilize a full-range, perfectly-tuned monitor configuration in a perfectly-tuned room. This helps them hear and feel every aspect of the music.

For the final QC pass (the Quality Control pass), they might use the best headphones they can afford to catch any artifacts before the song goes to market.

A good deal of mastering these days involves purging problems on an artifact level using tools such as

RX 10 Standard

If you have a series of tunes meant to be heard in a sequence, a mastering engineer also “tops” and “tails” the tunes. This means carefully positioning the start and stop points so the album has the right flow. Whether your material seamlessly segues from one tune to another, or requires specific pacing to get you out of one mood and into another vibe, it falls on the mastering engineer to execute these moves.

“Topping and tailing” is what we call it, and it segues nicely into another aspect of the job: metadata creation. ISRC numbers, UPN codes, song titles, artist information, all of it must be collated and imbued into the file, usually handled by the mastering engineer.

Keep in mind that there are a lot of different delivery systems out there. Streaming platforms may sometimes prefer a high res sample rate and a 24-bit resolution, but CDs require 44.1 kHz/16-bit files, and broadcast media still want 48 kHz/24-bit files. Some aggregators call for premade mp3s, and how these are encoded makes a big difference (RX, again, has a great MP3 encoder that naturally fights distortion).

Your mastering engineer keeps track of all these formats, as well as conventions behind modern day deliveries. Depending on how you’re releasing your project, mastering engineers send out dedicated files for specific formats. Each set of files is quality-controlled to ensure no glitch gets through.

A common misconception: stereo bus processing is not mastering!

It’s not hard to see confusion at the overlap points: Mixing and mastering engineers often deploy stereo bus processing on the song as a whole to get the effects they desire. But this doesn’t mean mastering and mixing are in any way the same.

Now, with generalized definitions out of the way, we can cover what differentiates mixing from mastering in a more granular way.

What does a mixed song vs. a mastered song sound like?

Here’s an example of a song, pre and post master, to illustrate the changes that take place at this final stage. Singer/Songwriter Pete Mancini asked me to master a live album for him, and this tune was one of my favorites on the project.

Now, here’s the master. Note that not much has changed, but you’ll feel an added excitement in the drums, an additional clarity to the vocal, a new separation among the harmonic instruments, and a reinforcing of this live performance’s cohesive groove.

Differences in mixing vs. mastering workflow

While I cannot speak for all mixing and mastering engineers, there are some key differences in workflow between these disciplines, regardless of genre. Because mixers receive multiple tracks, a chunk of their job, at least in the earliest stage, is organizational in nature—labeling and color-coding tracks, ordering them hierarchically in a DAW, and creating instrument groups and submixes.

Once this is done, a mixer will proceed to the more creative tasks of mixing—EQing, compressing, transient shaping, effectuating, and more.

Mastering engineers also need to be organized, but their focus is narrower. A typical mastering workflow goes something like this:

- Critical listening: what does this song need to hit its market and genre targets? Do I actually need to change anything? How should I order my signal path?

- Forensic fixes: are there clicks, pops, and distortions I should take out with RX? Any rough edits I need to massage?

- Levels: Setting final levels for the song based on genre, character, release format, and of course, the song itself (never forget: the song tells you what it wants to do).

- Sonics: Apply broad EQ and compression to improve tonal balance, while A/Bing the master with a gain-matched original version for quality control.

- Flow and reference: Consider how the individual songs on an EP or album work together, or sound against references. Is the character and loudness of each song uniform and consistent?

- Forensic fixes part two: did any of my work create artifacts? Are they best addressed with RX (simple, occasional momentary distortions) or an entire remaster?

- Metadata and export: Applying metadata and preparing export settings based on listening format.

- Final QC: Listen to things and make sure they a) have no errors, and b) sounds good.

The creative changes that happen during the mastering stage are subtler than those at the mixing stage. Most EQ changes are around 1 dB up or down. Compression happens as much for “box tone” as it does for effect—or, for transparency, if dynamics-taming is actually required.

Since changes are made to a stereo file, there will be unexpected consequences that need to be listened for. Has a cut in the low-end somehow added an edge in the presence range?

Put what you're learning to the test

Try

iZotope Music Production Suite Pro: Monthly

Ozone Advanced

Neutron

How much time does it take to mix or master music?

Depending on how a production sounds when it reaches the mixer, a full song mix can take anywhere from a day to a week. This time investment requires mixing engineers to develop a routine that enables focus and avoids ear fatigue. It also requires discipline in the face of external issues, from computer malfunctions to sinus infections.

Mastering, however, traditionally takes much less time. An album can be addressed in half a day. The quickness in time is tied to perspective.

Perspective

It’s important to note that the perspective behind each practice is different. The mixing engineer takes a deep dive into your music, shaping it over the course of days or weeks. This is by design and necessity: you want the engineer to pay close attention to every little thing in every track that contributes to the vibe.

Mastering engineers, however, aim to provide a balanced and objective perspective, so they try not to get lost in the weeds. They work quickly, deftly, subtly, and still manage to catch any/all errors.

Mixing engineers think about things like “how does this kick sample affect that kick sample.” Mastering engineers think about things like, “what frequency range is out of whack here across the board, if any?”

Mixing and mastering tools

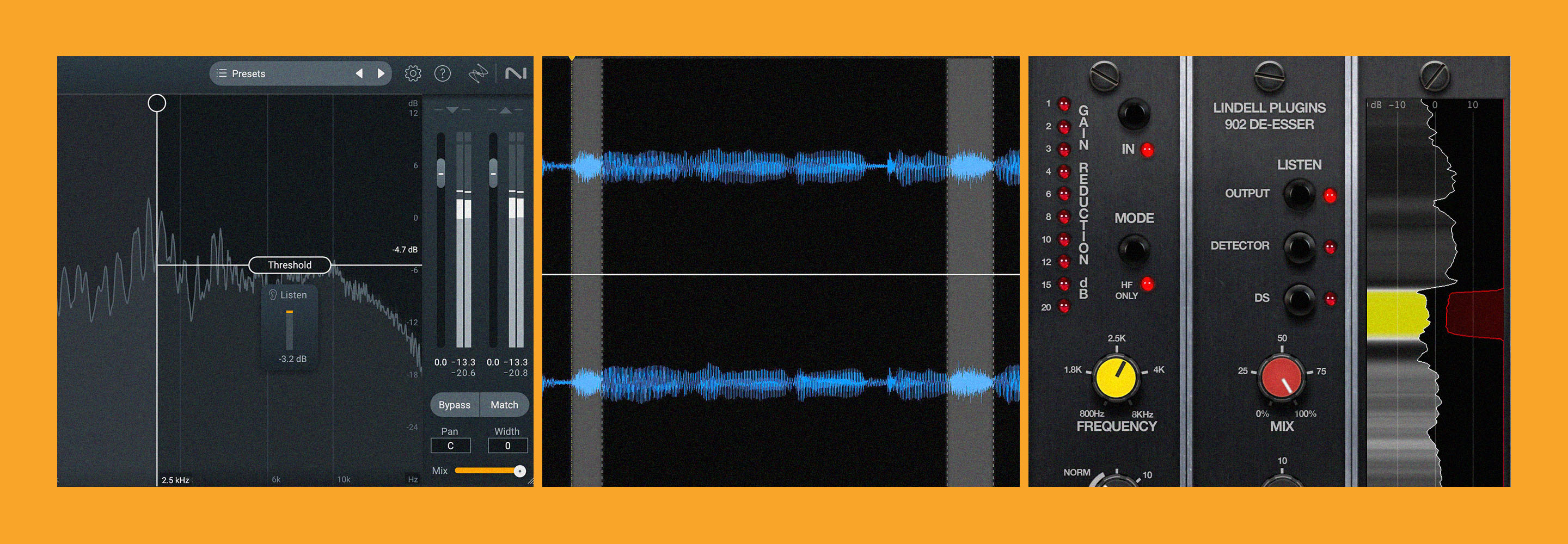

While EQ, compression, and limiting are applied in both mixing and mastering, the degree to which they’re used varies between both processes. Let’s use iZotope tools as an example and explore how they’re used in different stages of post-production.

Both Neutron and Ozone offer EQ modules. Look closely, and you’ll see that one plug-in is tailored for mixing, while the other plug-in is tailored for mastering. By default, Neutron offers a broad gain range for its equalizer: with a mouse, you can boost up to 15 dB in Neutron, and cut down to -30 dB. This is more suitable for mixing.

Not so in Ozone. In Ozone, the gain range is sized with mastering in mind: the mousable range is decreased, made subtler for the practice of mastering—you can only drag up to 6 dB and down to -10 dB. Ozone also offers linear-phase filtering which is arguably more suited to mastering than the mix. You can turn this on by default in the EQ preferences by clicking “Show Extra Curves.”

Linear phase filtering in Ozone

When you make curves, it will look like this:

Adjusting linear phase in Ozone

In the above screenshot, note how the phase response isn’t linear for the low end, but is for the mids and highs. This is a useful feature in Ozone: you can opt to use linear phase on a per-band basis; sometimes, it sounds better if you don’t use linear-phase on the lows, for example.

EQ is but one tool that both engineers use which can differ in application and features. Compressors also differ: Nectar offers an Optical mode, which emulates the subtle harmonic coloration and non-linear attack and release characteristics of classic hardware optical compressors, while Ozone does not. Ozone offers expansion, to breathe life into overly-compressed tracks, typically in a mastering session. Neutron Pro does not.

Another available tool that’s more relevant to mastering than mixing is a limiter, which is used to bring loudness levels to market standards. A song doesn’t have to be the loudest thing around, but it should be within the ballpark of similar music. Mastering engineers often use brickwall limiters to hit these targets without causing too much distortion.

Putting what you’ve learned into practice

For those who are new to the world of audio, mixing and mastering can feel a lot less accessible than production or playing instruments. I hope the points listed in this article have allowed you to achieve a higher understanding of what happens during these important post-production steps, so that perhaps you too will get in on the secret. Whether you’re starting to mix or master, start a free trial of a

iZotope Music Production Suite Pro: Monthly