An introduction to limiters (and how to use them)

Learn what a limiters are in audio processing, including when to use them, how to use them, and how to recognize when you’re over-processing.

The limiter plays a vital role in shaping the final loudness and preventing digital clipping in music production. However, achieving a commercially competitive level without negatively impacting the sound quality requires a deeper understanding. In this article, we’ll define what a limiter actually is, along with when to use them, how to use them, and how to train your ears to tell if they’re mangling your original sound source.

Follow along with the intelligent limiter included in

Ozone Advanced

What is a limiter?

A limiter catches the highest peaks of an audio source and applies “brick wall” compression that prevents them from exceeding the digital clipping point of 0 dBFS – or any other threshold you set. Limiters are often used to increase perceived loudness by raising the quietest parts of an audio signal while preventing the peaks from clipping. Limiting is also the final, and perhaps the most easily recognizable, step in mastering a song, allowing you to turn up the master to commercial loudness without unintentionally clipping.

Limiters generally fall into two categories:

Analog-style limiters, which are essentially very aggressive compressors – and may not behave in the ways described above. This is the NEOLD U2A.

Analog style limiter with limiter switch engaged

There are also digital brickwall limiters. These will be the focus of this article and covered in depth. The digital limiter below is the bx_limiter True Peak. iZotope Ozone is another example of a powerful digital limiter.

bx_limiter True Peak is an example of a digital limiter

When to use limiters

The most archetypal use of a limiter is at the very end of your mastering chain, applying no more than 2 dB or so of gain reduction in order to achieve a commercial loudness level.

Of course, rules are meant to be broken, so people use limiters in all sorts of ways these days – especially in the more aggressive genres, such as metal and EDM.

It’s not uncommon to see limiters on kick drums, on grungy metal basses, on snares, and other things that need to feel loud but also be tamed.

Still, the majority of limiter-talk tends to center on mastering and this makes sense: limiters are ubiquitous at the end of a mastering chain.

Think of the limiter as a bouncer, standing just outside the door of a club, keeping harsh digital overs outside of the proceedings, and doing so with the force of a brick wall, which brings us to…

Brickwall limiters

Now let’s talk about why we call them “brickwall limiters,” though the reasoning is fairly self apparent:

These processors catch the highest peaks of an audio source and ensure that nothing gets above the ceiling – or in other words, past the “brick wall.”

These limiters were an integral part of mastering In the CD era to make sure nothing got above 0 dBFS, the absolute limit of 16-bit and 24-bit formats. Above 0 dBFS there is nothing but distortion.

Even today, brickwall limiting is usually the final – and perhaps the most recognizable – step in mastering a song, helping engineers push the material to a commercial loudness without distorting the listener’s playback system.

These limiters have a ceiling control, usually set to between -1.0 and -0.1 dBFS to help avoid intersample peaks, which we’ll cover in a moment.

These limiters operate with infinitely high ratios, and implement a delay in the signal in order to see any peaks coming down the pike so that they can react smoothly to them – otherwise they’d just be clippers. Sometimes you can even tweak how far the limiter peers into the future with a dedicated lookahead parameter in your DAW.

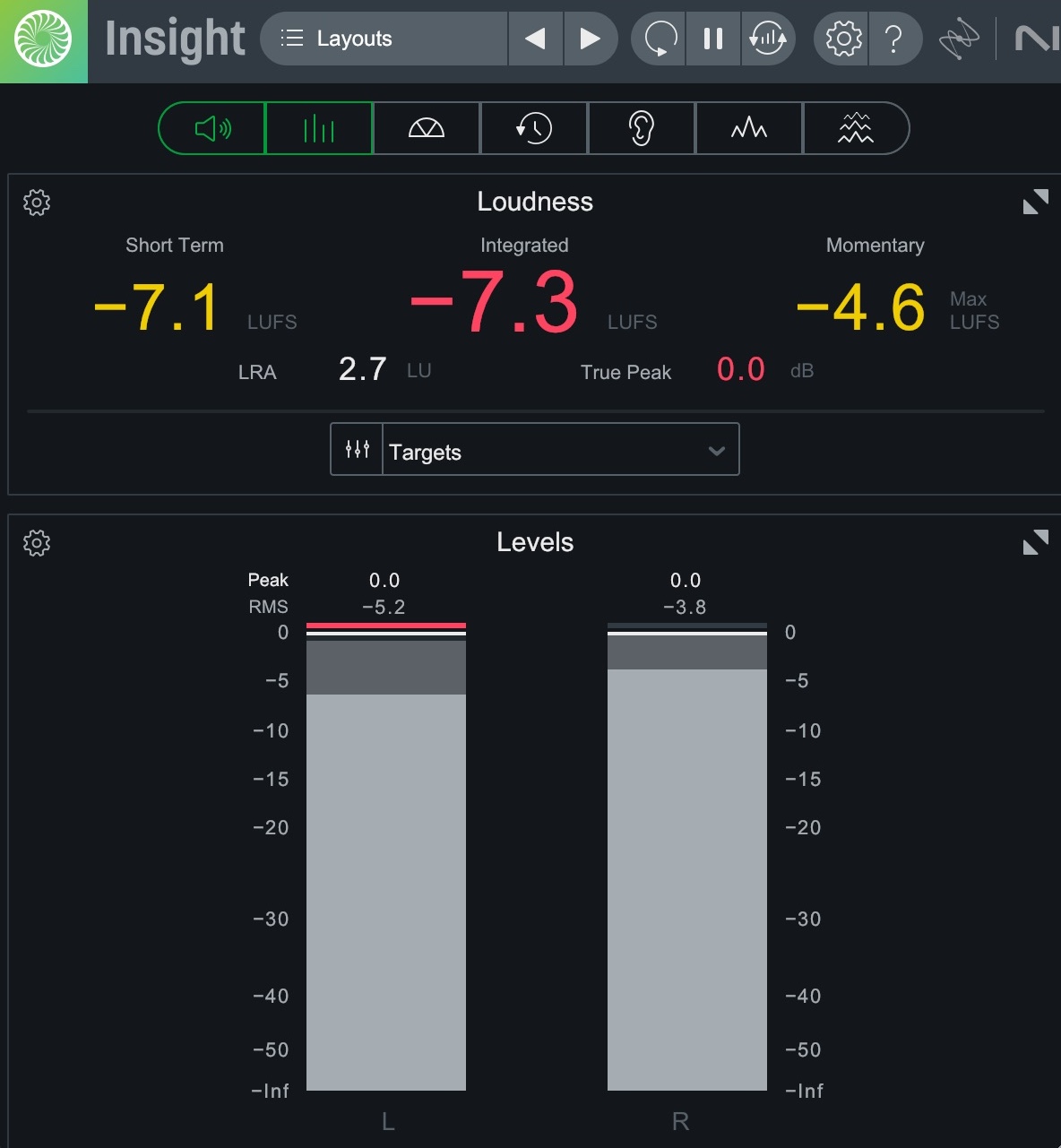

Whichever kind of limiter you have, know that it won’t always protect against clipping. You might need a different meter to keep track of intersample peaks or true peaks, like

Insight 2

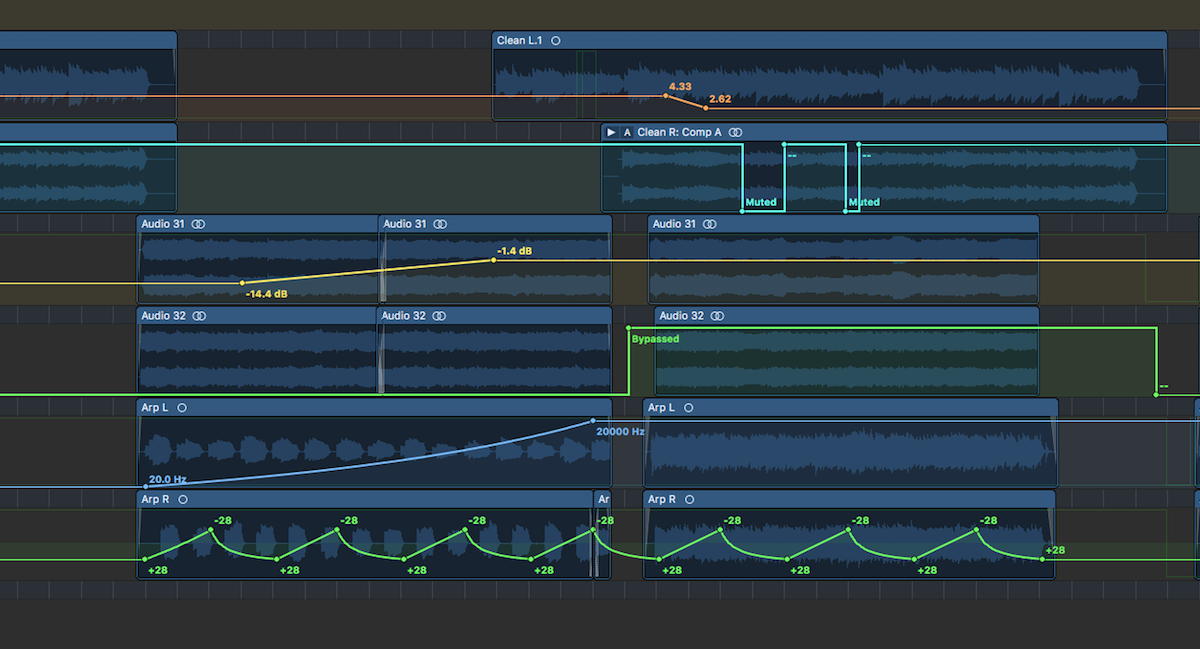

Limited material still hitting 0 dBFS

Intersample Peaks and True Peaks

We all know digital signal comprises many individual samples, roughly analogous to the many different images that make up a movie.

Our limiters ensure none of these samples go over 0 dBFS. But here’s the thing: sometimes the signal can jump over 0 dBFS in between samples. These are called intersample peaks—and limiters that aren’t set to handle them can’t protect against them.

People sometimes mix up the term “intersample peaks” with “true peaks,” but they are not synonymous.

Think of it this way: “True peak” is the be-all-and-end-all measurement of the signal, taking intersample peaks and everything else into account.

So if you want to guard against intersample peaks, you flip your limiter into True Peak mode.

Ozone in True Peak mode

Within the last few years, True Peak technology has come to be expected in any modern limiter. Nearly every viable limiter now offers true peak mode.

There is a controversial point to address we need to talk about:

Yes, many mastering engineers use True Peak limiters – but plenty of engineers dislike the sound of True Peak limiting, claiming these limiters affect the material in an adverse way.

Some would rather lower the output ceiling to ensure nothing got past 0 dBFS than submit a louder master with a True Peak limiter deployed.

Others don’t even care about True Peak distortion at all!

Bob Ludwig mastered many records over the years that peak as high as +3 dBTP, and yet is still considered one of the all-time greatest mastering engineers.

Take lossless versions of your favorite tunes from the last five years and open them in iZotope RX’s standalone application. Click on Waveform Statistics. I can guarantee that many of your favorite tunes easily exceed 0 dBFS.

Personally, I go on a case-by-case basis, depending on the needs of the client and the needs of the song. Over time you do begin to recognize the sound of peak limiting. Let’s see if you can hear it below:

Whether or not you want to use True Peak limiting is up to you or your mastering engineer. Use True Peak whenever you want to make absolutely sure there is no clipping when your audio is run through a D/A converter – or whenever the delivery specs require you to use True Peak limiting. Otherwise it’s completely up to you.

How to set up a limiter

Place the limiter as the last effect on your mastering signal chain and dial in the settings while listening to the loudest part of your track.

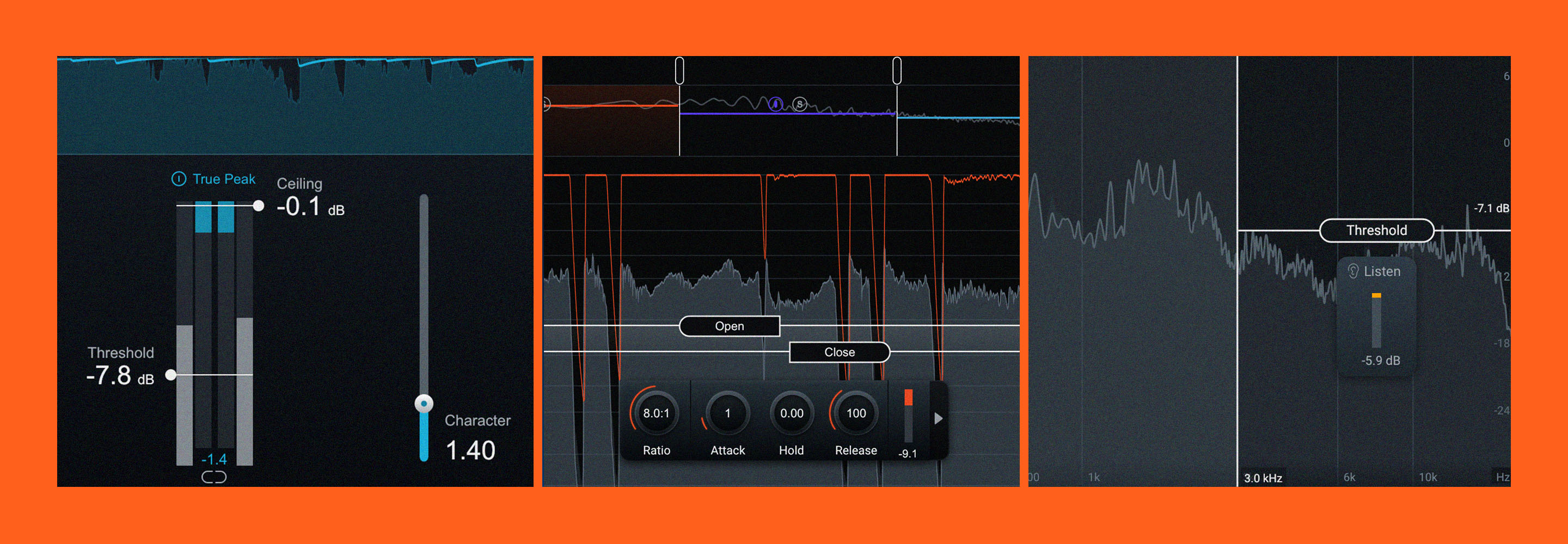

Limiters typically have three main controls: threshold, release, and output ceiling.

Threshold (sometimes called Gain): this control sets the level at which the limiter applies brick wall compression. If it’s a gain control it first allows you to make up any remaining headroom, getting your peaks right up near 0 dBFS. From there, the more you push it, the more limiting you’ll have, and the louder your signal will be. If it’s a threshold control you can first lower it to the tops of your highest peaks, and then the more you lower it, the more limiting you’ll have, and the louder your signal will be.

Gain control in Ozone

Gain control in bx_limiter True Peak

Output (sometimes called Ceiling): this parameter establishes the maximum level the limiter will allow. You often want the peak levels of your track to sit close to 0 dBFS without clipping, so the first thing you want to do is set your output/ceiling level at a level below 0 dBFS.

Engineers typically set this control to anywhere between -1.0 and -0.1 dBFS. Think of this control as the exact placement of the “brick wall.”

Output in Ozone

Release: this control sets the amount of time it takes for the limiter to stop working after the signal level drops below the threshold Some limiters have different release styles – Ozone is a perfect example.

Intelligent release controls in Ozone

Ozone lets you select among numerous different release modes that automatically adjust the limiter's release times to your audio's characteristics. Its IRC (Intelligent Release Control) technology lets you boost the overall level of your mixes without sacrificing dynamics and clarity. It uses an advanced psychoacoustic model to intelligently determine the speed of limiting that can be applied before producing audible distortion.

These modes are worth experimenting with as they each have their own sound. What’s more, you can customize this sound with the Character control.

Other limiters give more traditional release controls.

Release controls in bx_limiter True Peak

Esoteric controls: Some limiters offer transient shaping options, or stereo linking controls. Ozone’s Maximizer offers two stereo linking controls: one that focuses on the transient portion of the signal, and another that centers on sustained material over time. You’ll also note the Transient Emphasis slider, which applies transient preservation before the limiting stage.

The Brainworx flagship bx_limiter True Peak has different options from Ozone, including saturation (the XL control) and tonal parameters.

Whichever you choose, make sure to explore the esoteric controls in your limiter and see what they can do for the sound.

How to hear the difference in 5 easy steps

Here’s a step-by-step guide for tuning your ears to the sonic specificities a limiter imparts on your mix or master. I usually go through some iteration of this process every time I demo a newly-released limiter.

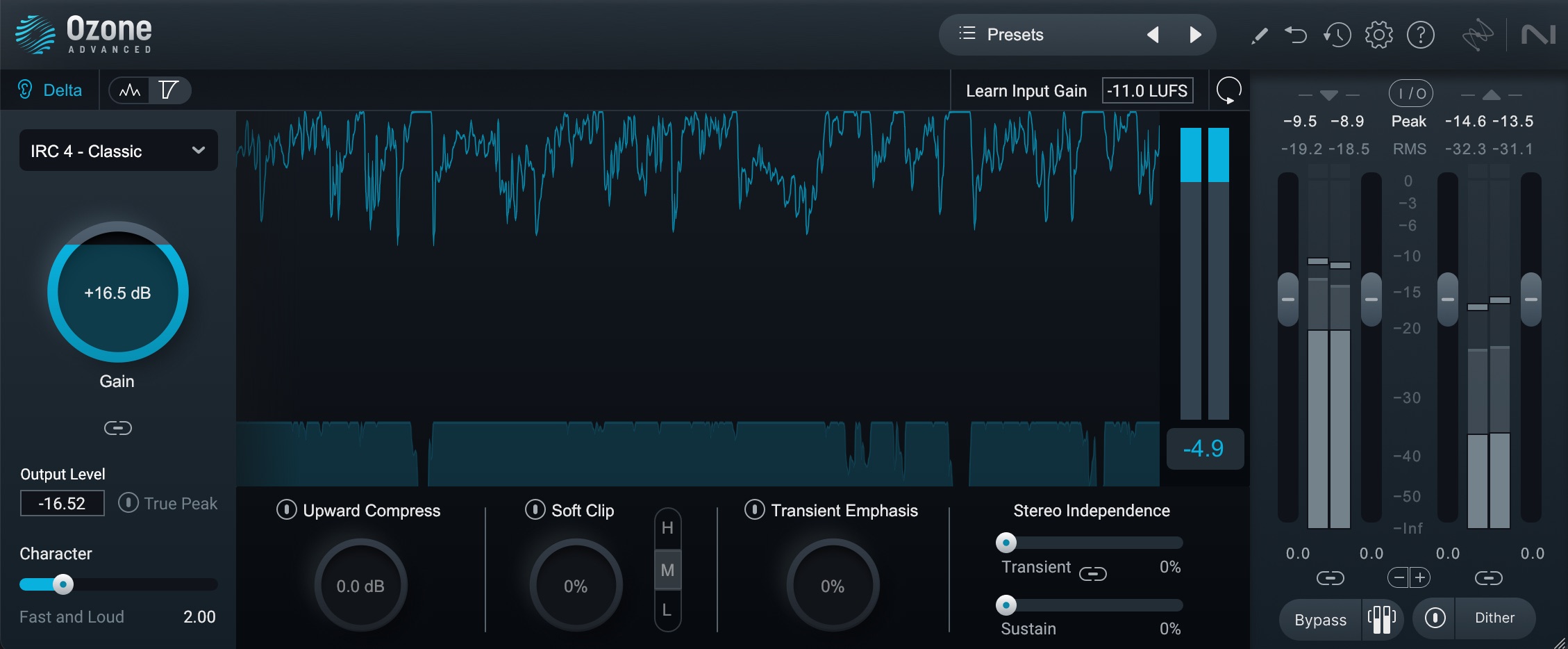

1. Link the limiter’s input and output as you tweak

Many limiters allow you to link the input gain or threshold control with the output ceiling, so that as you push one, the other comes down in level. This way your ears won’t be fooled by a satisfying – yet deceitful – jump in loudness, and you can better judge the moment you’ve gone too far.

Ozone Link Control

Link control in bx_limiter True Peak

Now that the input and output are linked, notice the output goes down in volume as you push the gain. The effect should be no change in loudness to your ear.

This makes it easier to identify distortion and over-limiting:

In this example, by 17 dB of input gain and up to 7 dB of limiting, we can definitely hear some distortion creeping in.

That’s great. We know we can’t push this hard. We’ve gone beyond our sweetspot.

But what if you’re a beginner or you don’t know how to find the sweet spot by ear?

Read on to train your ears to the distortion.

2. A/B between gain-matched bypass and limited signal

Let’s back the limiter down 1 dB and do an A/B comparison with the original signal.

Compare the limited signal with its bypassed variant and listen for the differences in timbre. Does the track feel narrower with the limiter on? Are the transients pillowy, softer, or otherwise altered? Does the groove of the whole piece seem different? Is everything now stagnant and lifeless with the limiter on? Does it feel farther away?

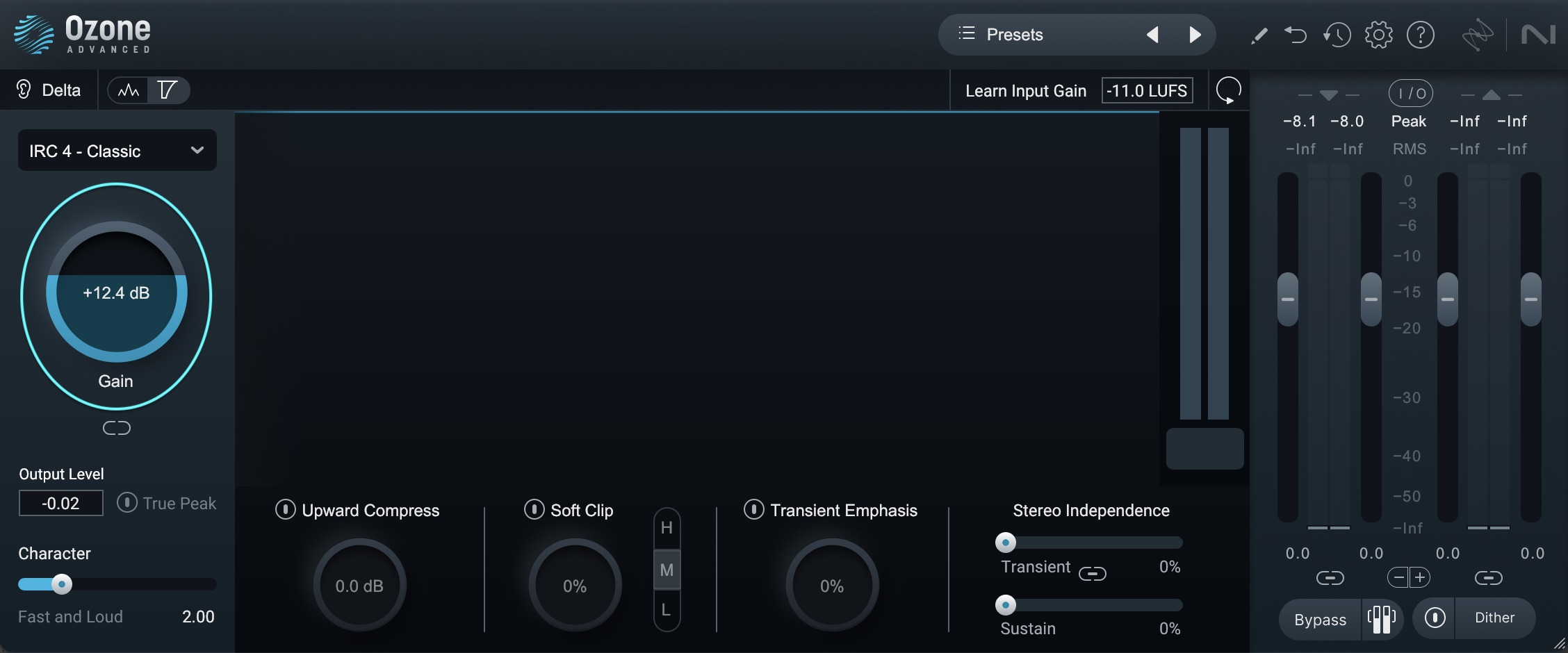

3. Hit the delta button

Ozone Maximizer now comes with a Delta button, which lets you solo the effects of the limiting. It’s very, very useful for teaching yourself to hear limiter distortion.

The Delta button in Ozone allows you to solo the effects of the limiting

Let’s listen to the limited track and compare it with the delta:

What you’re hearing now is the horrid sound of distortion. Granted, some of it gets masked by the main signal – and that’s some of the beauty of Ozone’s IRC modes – but when we move on to the next step, it should really be easier to hear the damage.

4. Go back to the A/B comparison

That’s right: go back to step two and compare the limited mix to its bypassed counterpart. Now that you’ve identified, heard, and internalized what the limiter is taking away, you should be able to hear the differences between the two more clearly.

Start moving parameters around and you’ll find you’re hearing what they’re doing. Less guesswork will go into tweaking the limiter’s time-constants and stereo interdependence options as your ear attunes itself to what the limiter is taking away.

5. Turn off gain link and set the ceiling you desire

Now all you have to do is uncheck the gain link button, and reset the ceiling somewhere sensible. For this mix, I’m going to choose -0.15 dB, and I’m going to click the True Peak button.

This mix hasn’t been crushed too badly, and it’s a respectable -10 Lufs Integrated with a max short-term lufs readout at -8.6 LU. If you want it to be louder than that, you have to employ creative tricks.

Some of these could be accomplished at the mix level, with limiting or clipping on drum bus to shear off the kick and snare, as well as parallel compression to individual submixes to reduce their peaks without adding to their overall loudness. Saturation can also achieve this effect.

Be careful with clipping in mixing though, and make sure you’re doing it for tone rather than straight level control. The flat tops incurred by clipping end up like scars in the waveform, and any phase shift or mixing of signals down the line can undo any peak level benefits, leaving just the scars, or tone – often on the side of the waveform rather than the peak.

At the stereo bus level, your options are a bit more hamstrung, and usually involve compromises to the mix. You could run into a clipper first, before the limiter, or you could run two limiters in series. Again though, proceed with caution if there will be a discreet mastering stage once the mix is finished, for the same reasons outlined above.

Here’s an example of me trying to do that using the two limiters we’ve been working with today, one following the other.

It’s still a compromise, but it’s not the worst one in the world. We’ve also used no other tool besides limiting to get to a competitive -8.2 LUFS integrated with short-term passages in the lower 7s.

It’s your turn to experiment with limiters

Limiters are getting better all the time. Ozone, for instance, employs assistive tech which intelligently sets your limiter, and goes farther by placing a dynamic equalizer before the limiter which helps achieve an even more transparent operation.

As limiters are changing all the time, it’s important to understand their basic functions and how you can use them in mixing and mastering to get the most out of your audio.