Ah yes, fake drums. When it comes to programming drums, we’ve got some great tutorials on how to make them feel more human, and how to build a sampler drumkit from scratch. But what about if some seriously fake drums come to you for mixing?

Perhaps they arrive with a directive attached: please make these drums sound as real as possible. What do you do?

In my experience, there’s no panacea. A lot of little moves add up to sampled drums that look and feel real. We’ll cover these moves below so you’ve got a better shot at achieving a more lifelike drum sound in the mix.

1. Avoid heaps of EQ and compression on the drum tracks themselves

Most drum-sampling engines offer well-balanced, well-EQd, and well-compressed samples right out of the gate. Many products advertise a mix-ready sound, having utilized console preamps, outboard EQ, and compression on the way in.

The sound is there. In other words, all that’s missing is the human element. This should fall to the producer. But sometimes your producer has skipped the human element entirely, providing you with lifeless, stuck-to-the-grid stems. Making matters worse, they can also arrive overly-processed from the artist or producer.

As the mixer, you’re in an unenviable position here. You must make these drums—drums not recorded with your song in mind—fit the tune. Yet EQ and compression have been salting and peppering the drums long before they got to you, so more of the same won’t help. If you try to compress and EQ each drum, you may find it sounds worse more often than it sounds better.

What’s an enterprising mixer to do?

2. Re-edit parts to improve the groove

We all want to make the drums sound more real. But they’ll never sound real if they don’t feel reel. A sampled drum in isolation is exactly the same as a human drum hit in isolation: both are samples under the microscope.

No, the programming is where it falls apart. You’ll notice problems when everything is quantized to an inhuman degree, or when the drums sound as though they're played with Vishnu’s many limbs. So see if the parts need editing before they need mixing.

Pay attention to the song. Note the groove of the bass, the feel of the guitar, and every other aspect of the arrangement. Keep a close watch on drum fills. Here drummers proudly display their humanity—many speed up in their fills, relaxing back into the tempo during the next measure.

Edit your sampled drums to fit the instruments at hand, keeping what we’ve just discussed in mind. If you’re presented with more than one drum stem (kick, snare, hi-hat, etc). make sure you group them. Be careful to edit all of them together so that no one region is left behind.

If you’re given any sort of overhead or cymbal track, take great care with your splicing. You cannot edit them in a way that disrupts their natural decay.

Here’s a drum part programmed in Superior Drummer 3, played to a bass part that pulls ahead of the beat. It’s been quantized at 43% before I bounced the track to audio. Note how bad it feels:

Start by editing the parts to feel more musical, and you’ll have an easier time achieving reality thereafter.

Do check with the producer, though, to make sure this is okay—perhaps they want the unreal sound, in which case, you’re not after realistic drums anyway.

3. Selective pitch-shifting can help

If you have drum head sounds that exhibit the machine gun effect (i.e., they sound obviously repeated with every hit) a little pitch-shifting is a good place to start. It can help replicate the sound of individually-slapped skins.

Let’s say we’re looking at a quick kick drum pattern. Here, you could grab the hit of shorter duration and pitch it down ever so slightly. The same philosophy holds true with a snare paradiddle.

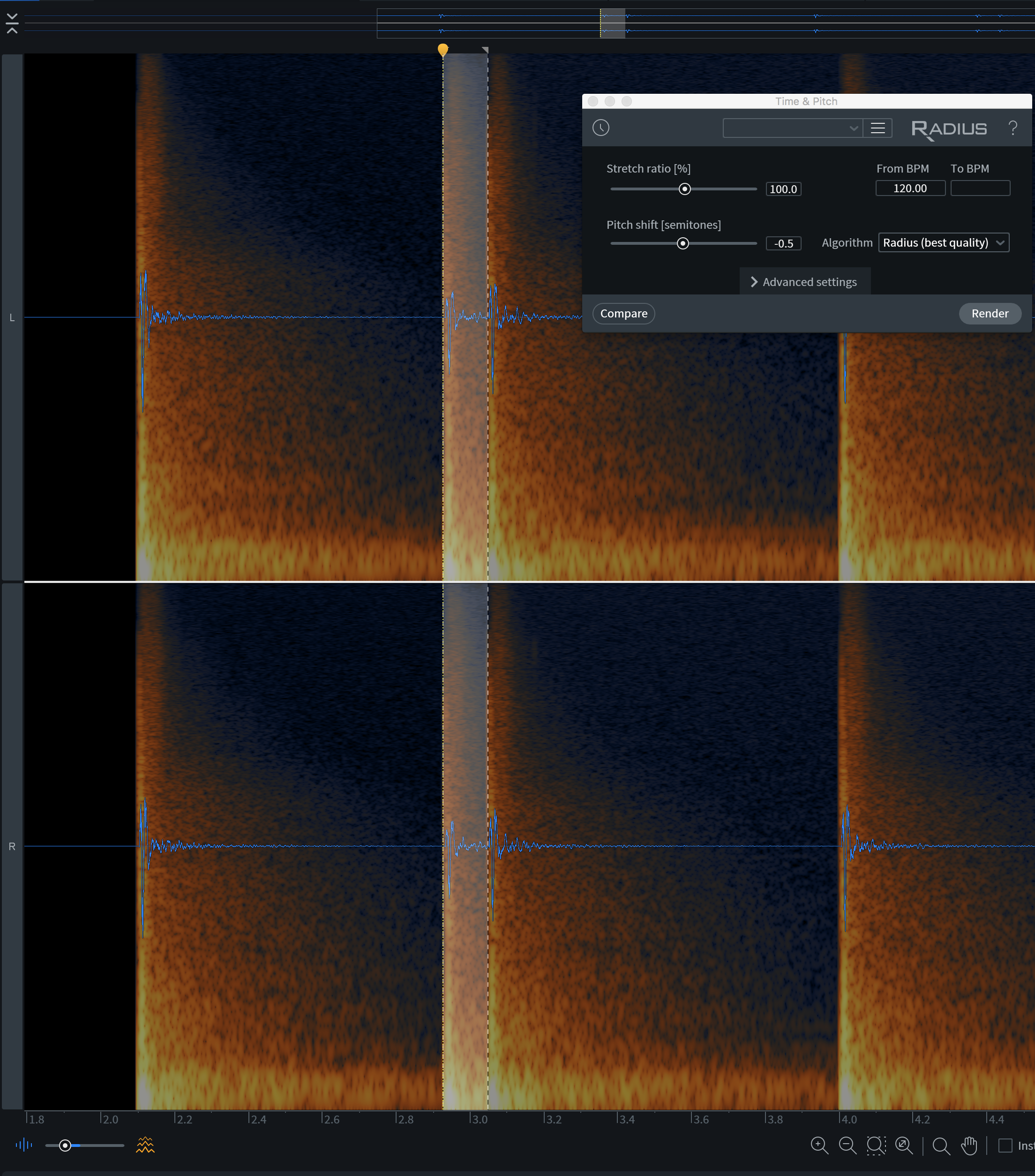

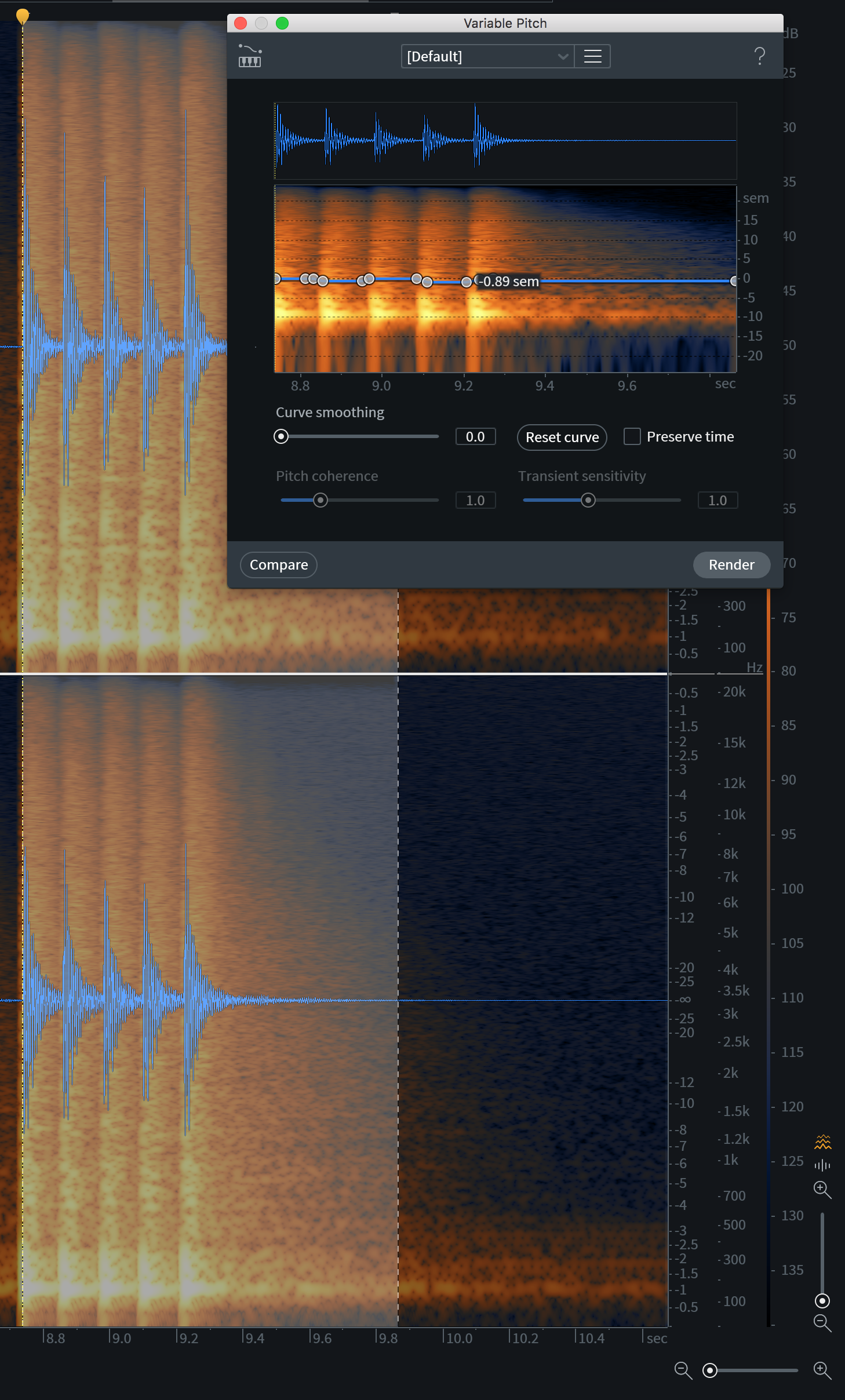

For the pitch process, I often load up RX and use the Time and Pitch module for kicks. I’ll use the Variable Pitch module for snares, for it seems to work better. Both do sound natural if used within reason.

Here’s an example of a drum groove that sounds really fake, programmed with Logic’s internal drums. This is a four-bar loop with quickly-triggered kicks and a paradiddle fill at the end.

If we were given this as dedicated audio files, we can open up the kick in RX and pitch the quick hits down like so:

We do the same for the paradiddle snare at the end:

The result sounds like this:

A mite better, I’d say. And small, incremental betterments are what we’re shooting for in achieving naturalness.

4. Pay special attention to the overheads, if provided

If the producer has given you an overhead track, you must pay heed, for the overhead track of a sample engine differs drastically from the real thing.

Consider that drum bleed can be dialed in on a variable basis, drum by drum. Perhaps the programmer has sent lots of snare bleed to the overheads, but left the kick completely out of the picture. In this scenario, pitch-play with the kick should be fine.

However, you’ll have a devil of a time with the snare, as any pitch modulation applied on the snare track will now “harmonize” with the snare in the overheads. You won’t want to apply the same pitch correction to the overheads, because your hats, cymbals, and ambiances will go down as well, which will sound quite strange and unreal.

The takeaway? An overhead track, if present, dictates the kind of processing you can do on the individual instrument—and you’d do well to remember that.

5. Pay special attention to hats and rides

This is not a repetition of the previous tip. Listen to a sampled ride or a sampled hi-hat, and you may feel they give away the fake. They’re hard to sample correctly—and they’re equally hard to massage. Our method of editing the pitch won’t work. EQ and compression will only seem to force their fakeness through a narrower bottleneck.

So try saturation to see if you can get them to sound a bit more real.

Here’s a beat with a ride cymbal going. The beat has been programmed in Superior Drummer, while the ride is from a Logic kit (just to keep it interesting). It shouldn’t work together at all, and, as we can hear, it doesn’t!

So let’s see what happens if we add some of Neutron’s Exciter in the midrange, just under where that cymbal hits, frequency-wise.

It has more life now; it breathes a bit better. For an extra-fine point on it, we can automate the parameters around the distortion, say the blend parameter. That might sound like this:

Indeed, harmonic distortion can be quite helpful in filling out artificial-sounding drums, so much so the process demands its own tip section.

6. Use Harmonic Distortion to fill out sounds

Let’s take that four-bar drum loop from the third tip—the one we re-pitched—and listen again:

If we apply the same distortion trick described above (a little excitement in Neutron, automated for effect) we can achieve something that feels as though the drummer was adding more stick, or more foot, at various parts of the song.

7. Remember your reverb tricks

Remember this article—the one about using multiple reverbs with your drum kit? These tips work wonders in the case of sampled drums. They help impart the verisimilitude necessary to fool the brain. So drill down the methods and apply them to your sampled drums.

I’ve also found it helpful in certain cases to drive the Warp section of a reverb like R4 to create a drastic, modulated sound. Feed this into distortion and compression, and it can make Logic drums feel a bit more actualized.

Listen to the following drum part:

Now, here are the kicks and snares sent to a bus. You can see the settings of R4’s Warp section in the screenshot below.

Note the position of the ‘Warp’ setting in this R4 preset

Dial that into the mix, and set it against the bass track, and it sounds like this:

It feels a little more real—though not nearly real enough. These are Logic drums, after all. Some sample packs will only get you so far, which brings us to our next tip.

8. Resample if necessary

Your producer might give you a prime directive to “make these drums sound real.” Unfortunately, they gave you the worst-sounding samples on earth. Good thing the producer already crossed the ethical boundary of sample replacement—now the path is clear for you to sample-replace the samples!

If you know you have a better kit on hand ("better" as in, “serves the music better”), use it. This is doubly true if you have fast and easy drum-replacement tech like Drumagog or any other such trigger in your slate of plug-ins.

Here’s the same snippet you heard from the previous section, with kick, snare, and toms sample-augmented, and the atmosphere and distortion techniques employed from earlier tips.

9. Going for Character? Go for the drum bus

If you need to squeeze an overall sonic signature out of these drums—something that fits the music better (a dark sound, a punchy sound, or a compressed sound) go for bus processing, rather than individual hits. Remember, the drums have already come to you equalized and compressed—your job as a mixer was to massage them into reality.

But on the bus level, you can make the broad-stroke choices to liven up or darken the kit, doing so in a manner commensurate with the material. Should you need squashing, expanding, or transient shaping, you can execute such character-based choices on the bus itself, as it’s now a cohered instrument, rather than a collection of samples. Plus, you can do it in parallel in handy processors such as Neutron or Nectar.

Conclusion: Don’t forget the other instruments

Remember, you’re not going for a human drum sound in a vacuum—you’re going for a human drum sound that best matches the rest of the song. Genre and performance are quite important. They might tell you the limits of how far you can go.

For instance, lots of modern metal music relies on the machine-gun quality of kicks and snares, so perhaps you don’t need to stray as far away from the samples as you might think, or else you stray too far from the competition. If you’re mixing something designed to sound more realistic, however, you’ll know things sound fake the moment you put up your massaged kit against the real instruments in the mix.

So, leave the instruments in as much as possible, and mix the drums to best spotlight them. That way they’re occupying their best role, regardless of whether they’re real or fake—they’re serving the song.

Indeed, if you remember that it’s all about serving the song, you’ll have a better shot at achieving realistic drums—even from a sampled kit.