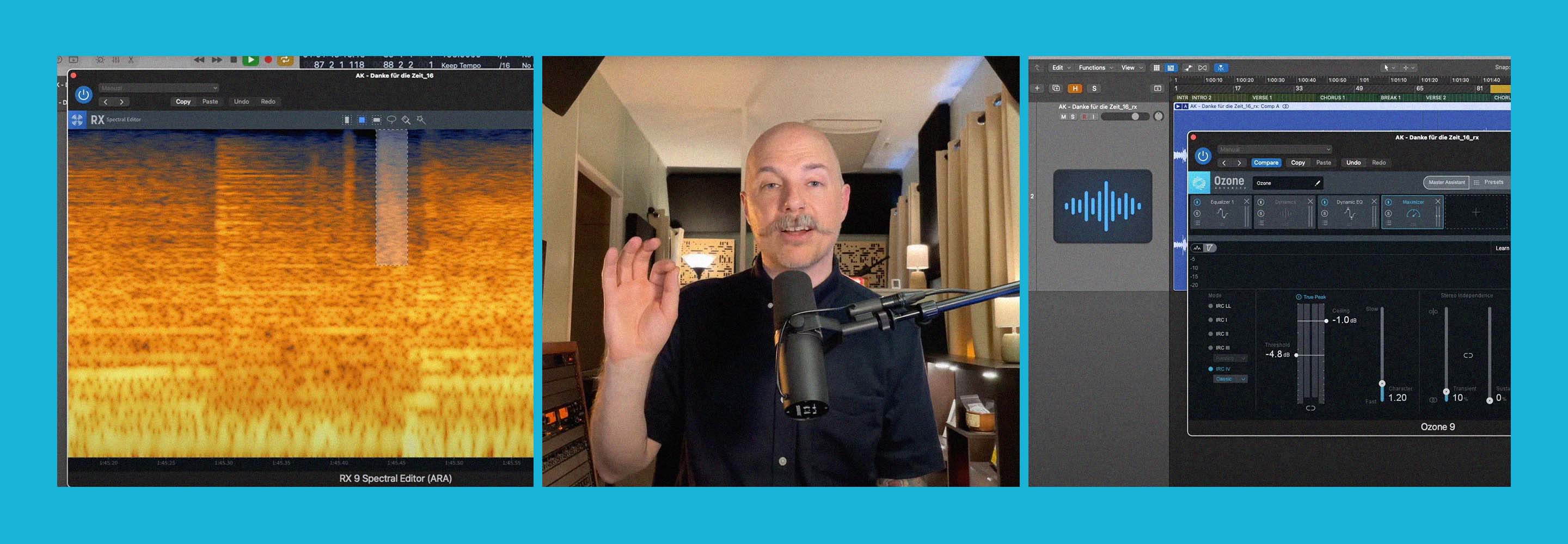

Mastering for Vinyl: Conversations with the Pros

Read interviews about modern music and mastering for vinyl from the perspective of various industry pros (a mastering engineer, producer, label owner, and an artist).

This article references previous versions of Ozone. Learn about the latest Ozone and its powerful new features like Master Rebalance, Low End Focus, and improved Tonal Balance Control by clicking here.

Since the resurgence of vinyl in the mid-2000s, sales have shown no signs of slowing down. But with vinyl’s return comes a new set of challenges for the aging medium—new genres with increasingly complex production styles, the major paradigm shift from analog to digital production, and evolving audio mastering standards (just to name a few). How does the old medium fare in a brave new world? Has mastering for vinyl evolved since its recent resurgence?

Part 1 of the article explored the unique characteristics of the vinyl format. We discussed the decades-long strategies used by cutting facilities and mastering engineers to ensure the best representation of modern music on vinyl.

In Part 2, we dive deeper into the thriving world of vinyl through the various perspectives of today’s vinyl-centric industry pros (a producer, a mastering engineer, record label owner, and an artist). Through each conversation, our goal is to understand the current trends, standards and innovations of the vinyl industry through the unique lens of each individual.

Ben Kane is the owner and chief engineer of Electric Garden in Brooklyn, NY. Most known for his GRAMMY-winning work as the engineer of D’Angelo’s Black Messiah, Ben’s recent work on PJ Morton’s Gumbo Unplugged album garnered him his third GRAMMY win (Best Traditional R&B Performance). Other notable artists under his belt include Emily King, Chris Dave, and CeCe Winans, to name a few.

Ben Kane at Electric Garden (Brooklyn, NY). Photo by Shotti.

Thank you for sharing your insights with us, Ben! As many are well aware, you’re a producer, engineer, and mixer who’s known for caring about your artists’ release on the vinyl format. You also work closely with a trusted vinyl cutting engineer in Brooklyn (Alex DeTurk of DeTurk Mastering).

Thanks! I enjoy listening to the vinyl format. I like having something tactile while digesting the music in album form. You get to appreciate music as a larger piece of art (an album) rather than as singles or individual songs. That’s definitely something important to me from the perspective of the art of record-making.

I agree with the experience of listening to the music from beginning to end. There’s a sort of ritualistic element that elevates the vinyl experience.

There’s something about that ritual. The fact that it’s analog and you’re listening to something that’s literally being played without any digital processing or algorithm. Maybe it’s one of those situations that’s more psychological, but I think it definitely adds to the spiritual connection to the music.

I find it really satisfying to listen to a record while I read the lyrics and see who played and worked on it. And what you’re saying with the ritual, it’s harder now in streaming to dedicate time, especially when we’re listening on these devices that are also tied into all the distractions of life—texts, emails, everything that’s constantly distracting us. Having music set aside from that allows us the space to appreciate it on a pure level. Even if you’re listening to it in the background, it’s nice to have it be disconnected from our phones.

I know you’ve been a long-time vinyl enthusiast. But for the general audience, what do you think is the reason for vinyl’s comeback even with today’s technological advancements?

There’s a certain element of nostalgia. And I think it came back for all of the reasons we’ve discussed—it’s special and there’s definitely an audiophile element to it. And as a listener, you might be using a streaming service and suddenly stumble upon a great-sounding record. Having that physical ownership of a vinyl record ensures that you get to fully appreciate music you’ve discovered. You own music that you really care about and it becomes part of your life forever.

And because of its analog technology, it’s something that you can put on a shelf and listen to a hundred years later. They’ve even sent a phonograph record into space.

I agree that vinyl complements today’s streaming culture. Even with premium streaming services, many of the music you’ve downloaded can just disappear from your library. The only way to really own music is by buying a physical copy.

Everything is so fleeting and ephemeral nowadays, so it’s nice when people want to buy something you’ve created and own it for the long term, not just stream it until they find the next artist comes on.

Speaking of music you’ve created, what made you decide to jump into the world of vinyl?

I’m usually not the one driving that decision for the artists. But I do work with artists whose fan base is more inclined to buy vinyl because of their appreciation for analog sound which is the aesthetic we sometimes go for. The artists and I tend to share a mutual appreciation for the format as well. So it’s kind of an obvious choice for them to put out a vinyl release for their fan base.

Can you tell me more about Electric Garden and its strong analog ethos?

You can work in our studio 100% analog. You can record multitrack to 2” tape. We have an analog console, Studer 827 tape machine, analog outboard equipment and effects for processing, and ½” 2-track for printing your mixes. You can—and some do—work entirely in analog at the studio. It’s also set up for hybrid with Pro Tools and mixing in analog, for instance. Any combination that you want.

The Electric Garden control room (Brooklyn, NY). Photo by Frank Oudeman.

I’ve noticed that there are many fewer problems with reproducing my mixes on vinyl when it’s a project that’s completely analog (recorded analog and mixed analog). Because the transient response of the tape is a lot more similar to what you get with vinyl as opposed to mixes that have lived in the digital realm.

Specifically with today’s modern music, what are some challenges you’ve dealt with when it came to releasing music on vinyl?

Sibilance can sometimes be an issue, but Alex DeTurk does a good job of handling the sibilance on his end. There’s a de-esser on the chain of his Neumann lathe with a lookahead that sounds really natural.

There were a few instances, however, where we had to attack the sibilance a little more aggressively. On the record I did for Chris Dave and the Drumhedz, there were a couple moments in the album that were intentionally harsh and sibilant and made it difficult for proper playback on vinyl. So that had to go through a harder amount of de-essing than usual.

Additionally, there were occasional moments in the album where I played with low-end phase, being weird and creative with the mix. Naturally, this doesn’t translate as well on vinyl, especially when you’re trying to do weird, wide bass effects that are meant to trick your ears. There’s not a great way of recreating that on vinyl due to the physical restraints of the medium.

Were there instances where you had to compromise a certain level of artistry for those cases? How did you adapt?

The reason why I’m so comfortable working with Alex is because at this point, I know that he can translate what we’ve done in the digital master onto vinyl as faithfully as possible.

Working within the limitations of the vinyl format, there are decisions that need to be made. But almost never will my decision be to alter the spirit of the original mixes. For instance, by turning down the bass to get more volume. I think it’s important to maintain the spirit of the original production as much as possible. And I do trust Alex to take us there.

When I attend a vinyl cutting session, I’m often there as a spectator and as a student learning and asking questions about what’s going on. Anything that he’s doing as far as having to make the bass less wide or de-essing something, he only does out of necessity. If you’re willing to give a person of that expertise the time to address specific concerns on your record, it’s a lot more possible to maintain that original quality of your music on vinyl.

Records not sounding true to the original are mostly due to not hiring a highly skilled engineer to cut your lacquers and instead leaving that decision to the vinyl pressing plants. There may be people with a good level of expertise at the plant. But as a listener, I can definitely tell the difference. Either there’s not enough time or effort spent or there’s a lack of similar expertise.

People don’t realize that there’s a step worth paying money for that is integral to having a good vinyl record in the end. And that’s hiring a highly skilled engineer to cut your vinyl master.

I agree. When it comes to vinyl production, it can be easy to cut corners financially and have the audio quality be sacrificed first.

I’ll say, as a mixing engineer, I am often involved in the process of ensuring that we have a good quality vinyl record. Even a lot of label records don’t realize how important these things are to getting a good quality record. People who purchase vinyl care about listening. A lot of them are audiophiles or people who want the experience of listening to what the artist and producers intend to create sonically. So compromising the audio quality is the worst place to cut corners. Because the listeners do care.

One thing that was clear to me—the art of engineering and mixing is definitely a skilled craft that people learn through apprenticeship and through being taught by an expert in the craft. I especially feel that the art of cutting lacquers and mastering for vinyl is a similar thing, but more precise and detailed. With mixing, the results are more open to interpretation—if I mess something up, it’s probably not going to actually destroy the product, it will just change it. As opposed to cutting vinyl, if you haven’t learned the skill, it will completely destroy the product and make it unplayable.

Ben Kane with Electric Garden’s extensive inventory of outboard gear (Brooklyn, NY). Photo by Shotti.

Were there any unexpected experiences and realizations as more albums you’ve produced/engineered got released on vinyl?

Particularly with Emily King’s previous album The Switch, I dealt with an independent release so I took on a greater role in the album’s vinyl production, making sure to get feedback from the customers who bought it. Occasionally, I would hear that there was something wrong with their vinyl skipping and that there was a defect. I talked about this with the plant and the reality is, for about a thousand vinyl records, around 20–50 of them will probably have some level of defect. Even with the plant running at their best, there could be some defect on a few discs a decent percent of the time.

And nowadays, it’s more common to do small batch runs which could introduce more concerns versus a larger vinyl order. A typical vinyl order today would be for around a thousand or a few thousand records with the exception being bigger artists. D’Angelo’s Black Messiah sold 50,000 vinyl records right off the bat, but that’s an exceptional example as far as how much vinyl is sold today. However, 30 years ago, even 50,000 would be considered a small run.

Back in the 1970s when vinyl was in its heyday, warming up the machine wasn’t much of a concern because you would have one similar album on the press running for much longer. Fast forward to today, smaller vinyl orders have become the norm. I sometimes work with artists that have about a thousand records run at a time, and that’s a pretty short amount of time for the machine to be running, potentially leading to a higher margin for error/defect.

There’s another interesting thing that I’ve learned in the audiophile community. If you dig very far into Discogs and look for an album with a worldwide appeal and was pressed multiple times, you’ll discover people having countless debates over which version is the best version. For example, with a Led Zeppelin album, you would hear opinions about how the presses out of Germany would be the loudest. Maybe the Japanese pressing would have the most bass whereas a different press would have the quietest noise floor.

Back in the day, the only way people heard music was on vinyl. There was nothing to cross-reference what you’re listening to besides the lacquer reference discs cut by the cutting engineer. So you wouldn’t know right away how the music was gonna translate for commercial consumption until it’s pressed to vinyl. That would be one of the factors as to why records like the Led Zeppelin album would have so much variety through the years. With today’s modern music, we know for the most part how the artists, producers and engineers intended for the music to sound. And when their music gets released on vinyl, they’re happy that it got out relatively close to what they wanted sonically in the original masters.

Speaking of listening to how music translates to vinyl, what’s your thought process when it comes to evaluating and approving test pressings?

Test pressings are an area where it seems there is a lot of unnecessary confusion among artists and labels. It’s really a period of time where someone intimately familiar with the final master should listen for a few very specific things across all of the five or so test records provided.

You’re really looking for unintended errors in the plating or pressing process. The actual test presses are made in the worst sounding period of the press where the machines are warming up, so they generally have a higher noise floor and more incidental pops than usual. If you hear a pop or a whirring that is persistent across every test pressing, there is a problem that could be corrected.

Since vinyl is often the side-release, labels often don’t have a strong system in place for this important quality-control step and independent artists often aren’t aware what to listen for or don’t have a dependable record player for testing.

Would you say that vinyl can effectively capture modern music in your standpoint?

There’s a huge variety of music out there, but yes, vinyl can absolutely sound great paired with a lot of today’s modern music.

However, modern music does push some aspects of the limitations of vinyl as far as loudness, sibilance, and low end are concerned. When you take that into account, vinyl may not be the best medium for all of today’s modern music. And in which case, when going to vinyl, it’s either for the ritual of listening to vinyl because they like the experience of it, or just as a novelty. Not because it’s a particularly great representation of the sonics of the music. And that’s fine too.

On the flip-side of the coin, a lot of the streaming formats are doing a horrible job of representing music that’s being made today. People send me Soundcloud links that are streamed at 128 Kbps MP3 (which we all can agree is an insufficient format for listening even 20 years ago) and don’t seem bothered. Vinyl definitely is VASTLY superior to some of the things that people today think is acceptable.

Do you think vinyl is here to stay in the long run?

On one hand, I think vinyl is absolutely here to stay because it is virtually indestructible. Even if we lost all our technology from the apocalypse and we find a vinyl record in the rubble from something similar to Pompeii or the Egyptian ruins, someone could probably find a means to play it. Any technologically advanced society could quickly figure out how to listen back to the audio from a vinyl record. Which is why we sent a vinyl record to space.

I think that’s a better way to answer that question. Honestly, I don’t know if it will remain a commercially viable product 50 years ahead into the future. Who knows about the trends of that time. But I’d rather not give that answer, I liked my first answer better.

The Mastering Engineer: Eric Boulanger of The Bakery (Los Angeles, CA)

Eric Boulanger is the owner and chief mastering engineer of The Bakery, located on the Sony Pictures Lot in Culver City, CA. His current audio mastering portfolio runs the entire gamut of genres from rock (Weezer, Green Day) and traditional pop vocal (Barbra Streisand, The Carpenters) to movie soundtracks (La La Land, Bladerunner 2049). Most recently, he swept the major awards at the 2018 Latin Grammys for his work on Luis Miguel’s ¡México Por Siempre! (Album of the Year) and Orquesta Filarmónica de Bogotá (Best Engineered Album).

Eric Boulanger cutting a lacquer master at The Bakery (Culver City, CA). Photo by Jei Romanes and Gaile Deoso.

Hi Eric! Can you give us a brief background on The Bakery and how you got into vinyl?

The Bakery is a mastering studio located on the Sony Pictures Lot in Culver City, CA. We opened in 2015 and that was following my time with The Mastering Lab and mentoring under Doug Sax. That’s where I got my start with vinyl, back in 2009 when Doug decided to bring back vinyl and build a vinyl studio at the Mastering Lab.

My hands were full from building the room, figuring out how the heck to cut vinyl, learning the cutting lathe, reverse-engineering the lathe, putting everything together and then going from there.

You were really thrown into the deep end!

What's funny is that I’ve never purchased a vinyl record at that point in my life. By the time that I was at the age to be buying my own music, vinyl was gone. Only CDs were sold. So in the beginning, I had zero experience with vinyl and my first task was to build the cutting lathe. It was a little backward.

So vinyl wasn’t a natural inclination for you at the start?

Well, I enjoyed it especially at the time because it was an insane challenge, mainly because of my inexperience back then. And the fact that The Mastering Lab’s lathes were so highly custom—unlike any other lathe you’d come across.

Think of the tube amps and suspension that were all custom. The funny part about that old system—the reason it was so custom was because back in those days, when Doug would’ve been buying all these systems, there was only one distributor for everything in the country (Gotham Audio). People with accounts who bought lathes could also buy spare parts—which were cheaper than buying the whole system (the distributor would take a huge cut when people bought the whole cutting system). So, instead of buying a whole system, Doug got together with friends to acquire “spare parts” without the distributor catching on to him.

However, there were always certain spare parts that you weren’t allowed to buy because then you couldn’t put together a whole system. So guess which parts those were at the Mastering Lab? The amps, the protection panel, the suspension...these all had to be custom-made.

Having worked on vinyl records for a decade, what do you think is the reason for its comeback?

I believe it’s come back because the allure of instant gratification and convenience is over. We’ve figured it out. It’s there, it’s not going anywhere. So there’s nothing intriguing about being able to do that anymore.

Now, kids who haven’t even had the experience of going to a store to buy music suddenly have this experience where you have speakers in a living room and you can invite friends over. Put the record down and listen to the whole thing. You can get into a band, read the artwork and play it for your friends and start a little library that looks cool in your room.

That’s an experience you can’t get any other way. And the technical specifications of vinyl force you to do that. You can’t go jogging with it, you can’t drive with it in your car. We’re not selling the format. We’re selling the experience.

What are some challenges you face the most often when mastering for vinyl?

The single greatest challenge is what everyone faces. The lead time at the plant. At best, it could be something like three months before you could ever hear a test pressing. That obviously puts pressure on the record label, pressure then on the artist, and ultimately, pressure on us. There is very little wiggle room for the vinyl cutter if anything goes wrong. Of course, the reason behind the long lead time is that there are so few pressing plants on the planet, unlike during vinyl’s heyday.

For example, when you have to recut a master, you might only find out three months later as opposed to the next day. It’s really aggravating and that’s why we partnered with NiPro so we can send as much metal as we can over there. They do QC on the metal which gets the metal stamper done quicker and more reliably. If there are any egregious errors, it would be caught then and it won’t slow anything down. So even though it might take three months before we get a test pressing, we already know from the QC that we’re at least in the ballpark of what ends up becoming the stamper.

Eric Boulanger with Wilbur at The Bakery (Culver City, CA). Photo by Jei Romanes and Gaile Deoso.

What are you thoughts on vinyl being an imprecise format by nature?

The aim with anything we do in mastering is that no matter the format, the goal should be that everything sounds the same. Of course, physics dictates otherwise. But, since we have to deal with that reality, that’s what makes us engineers. It’s being able to manipulate what you’re doing, how you’re doing it, and be able to get the best results out of it.

And specifically for vinyl being the “finicky” format, that imprecise nature is actually helpful in the production side of things because people get less neurotic in a way. With digital masters, people might nitpick every single little slight sound. For example, someone hears a chair move in the middle of a performance and you’re there RX-ing it out.

With vinyl, there’s so much that can go wrong even in between pressings. No two records are ever made the same that ultimately, no-one ends up obsessing over the smallest details. And so I think that makes getting a performance in the production a little bit better.

Doug Sax also mentioned how the limitations of vinyl are also part of its charm. People tend to say that vinyl is less fatiguing but I think it’s also due to its limitations.

You get a break after ~20 minutes, that’s number one. Everything about vinyl also defines what we consider an album even in digital and streaming land. The concept of a 10-12 track album, the 3 ½ minute song—all of these details somehow rose from the limitations of vinyl back when these genres were being born.

In your opinion, is vinyl able to represent modern music?

Certain genres like EDM with those intense, phasey low end synths and harsh highs would’ve never been invented in the vinyl days because you just couldn’t get anything to play those types of music. There are certainly genres that were born in the digital age because it’s the only thing that can actually create those sounds.

So now, fast forward to 2019 where we do have these projects wanting to be released on vinyl. Well, they ain’t gonna sound the same. But will it “represent” the original track? Sure. It will get the idea across, but that’s a clear instance where vinyl is definitely not gonna be the better sounding format.

But The Bakery does have tricks up its sleeve.

That’s where engineering comes in. You’ve got to put the square peg in a round hole. And us mastering engineers figure out how to do that.

The half speed cutting system really helps deal with the demands of modern music.

There’s no question that it helps. And the best part about the half speed design is we use so much less power to cut. It’ll add years of life to our cutterhead. There’s less strain everywhere, it can produce a better sounding record and the system’s happier every single day.

One of the best examples of half speed cutting in modern music is N.E.R.D.’s No One Ever Really Dies. That one was not quiet. That and the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra’s 1812 Overture, which were both actually done around the same time.

That’s with Paul Blakemore and Producer Bob Woods, right?

Correct. When Bob Woods got the test pressings back from that, it was one of the most honored calls of my life. He called to ask me what the hell I did. No pun intended, but he was…blown away.

Eric Boulanger and his violin at The Bakery (Culver City, CA). Photo by Jei Romanes and Gaile Deoso.

Do you think vinyl is here to stay?

Honestly, no. The way I see it is, the industry and people are going to figure out how to enjoy the same experience as we do with vinyl in a more technological means. And I think when that becomes common place, vinyl is gonna go again. Because then you won’t have all of the limitations we’ve just discussed. We don’t need to be pressing records. It will take a lot less time and money.

The Label Owner: Sebastian Wolff of Materia Collective (Seattle, WA)

Materia Collective is a Seattle-based record label that specializes in video game music. Since officially launching in 2017, Materia has helped multiple video game composers and independent video game developers produce soundtracks, license cover albums and manage their copyrights. They’ve since released multiple Billboard chart-topping records (Project Destati and Rozen) and is a consistent best-seller on Bandcamp.

Sebastian Wolff of Materia Collective

Hi, Sebastian! Tell me a bit about Materia Collective and how it came about?

Materia’s goal has always been to bridge creators and fans.

Our video game community grew out of a small cover song project in 2015: An 87-track love letter to FINAL FANTASY VII and Nobuo Uematsu’s rousing soundtrack, with contributions of nearly 200 artists. After the praise and feedback from fans, we continued our journey in producing additional tribute albums and soundtracks.

Materia now boasts a plethora of digital releases, vinyl, CDs, and sheet music books. We empower creators within game audio community, elevate their work, and nurture an ever-growing soundtrack audience.

What do you think is the reason for vinyl’s comeback in the game audio community?

It’s fascinating, right?

And it makes sense. Physical memorabilia is meaningful, and important to anyone celebrating nostalgia on a personal level. Particularly within the vgm/game music communities, vinyl sits in the sweet spot: It is unique, tangible, gorgeous, high quality, often limited, and it rewards fans with more replay value than most other game merchandise.

The polarization of consumer models is the other consideration: An era of digital disposability is upon us: digital media is streamed, viewed, accessed; not purchased. That shift has accentuated the significance of individually-owned physical media. The fans who share our loves agree, and I hope we can continue rewarding their passions!

Materia Collective vinyl records

What made Materia decide to jump into the world of vinyl? Was vinyl ever a natural direction for your label, or did the demand from the video game music community come out of left field?

It was a natural progression—on an accelerated timeline. The demand has been there for years, long before we produced our first vinyl, and we are joining an established industry that has paved the way.

Materia gravitated towards vinyl, in part due to endless requests on social media, and in part due to our love for pretty premium things.

Options for deluxe releases on digital storefronts taper off with perhaps a digital booklet and MFiT, but with vinyl, the options are endless. Endless! PANTONE inks and shiny foils, embossing touches, unique papers and box assembles; bottomless options to push more art into the forefront and highlight typography. Hexagonal die-cut vinyl, strings, Alien blood-filled discs; holograms and glitter; vinyl that glows in the dark, vinyl on ice, vinyl on chocolate, vinyl on x-rays…it’s hard not to appreciate the medium and the—at times—excessive personality that can be imbued into the presentation alongside the music.

It’s wonderful to capture the richness of games’ respective universes, and instill a piece of those worlds into vinyl. A Gesamtkunstwerk, if you will.

Legend of Zelda, Pokemon, and NieR: Automata soundtrack cover albums on vinyl

What challenges have you encountered most often when releasing music on this format?

I love creative ceilings. Thankfully, the manufacturing world is in no short supply—largely all memoirs of the past, discarded and forgotten in a digital industry, but resurfacing alongside the growing appreciation for the medium.

One of the biggest challenges—and most rewarding parts—is finding creative solutions to physical restrictions, primarily those imposed by physics. Color is the biggest limitation; there are only so many colors and transparency combinations you can have in a hand-poured record without sacrificing audio quality. Matching vinyl colors to print colors is often impossible, certain colors cannot be combined into a working disc, the list goes on. Manufacturers often hesitate to experiment in this regard, so it can be tough creating a unique and high quality product.

Were there any unexpected realizations when you jumped in to the world of vinyl as a young record label with a niche audience?

The biggest realization was the necessity of experts—and the amount of human touch for all the nuanced steps along the process of good craftsmanship.

The other unexpected response has been the reaction of the community: By and large, other labels are friends and partners, which is not always the case in the music business worlds. The shared attitudes towards the passions of a fan-centric community is its own reward, and we are honored to be part of a growing creator community that celebrates alongside fans.

Overall, it has been a wonderful and rewarding journey so far, and I can’t wait to share our next adventure.

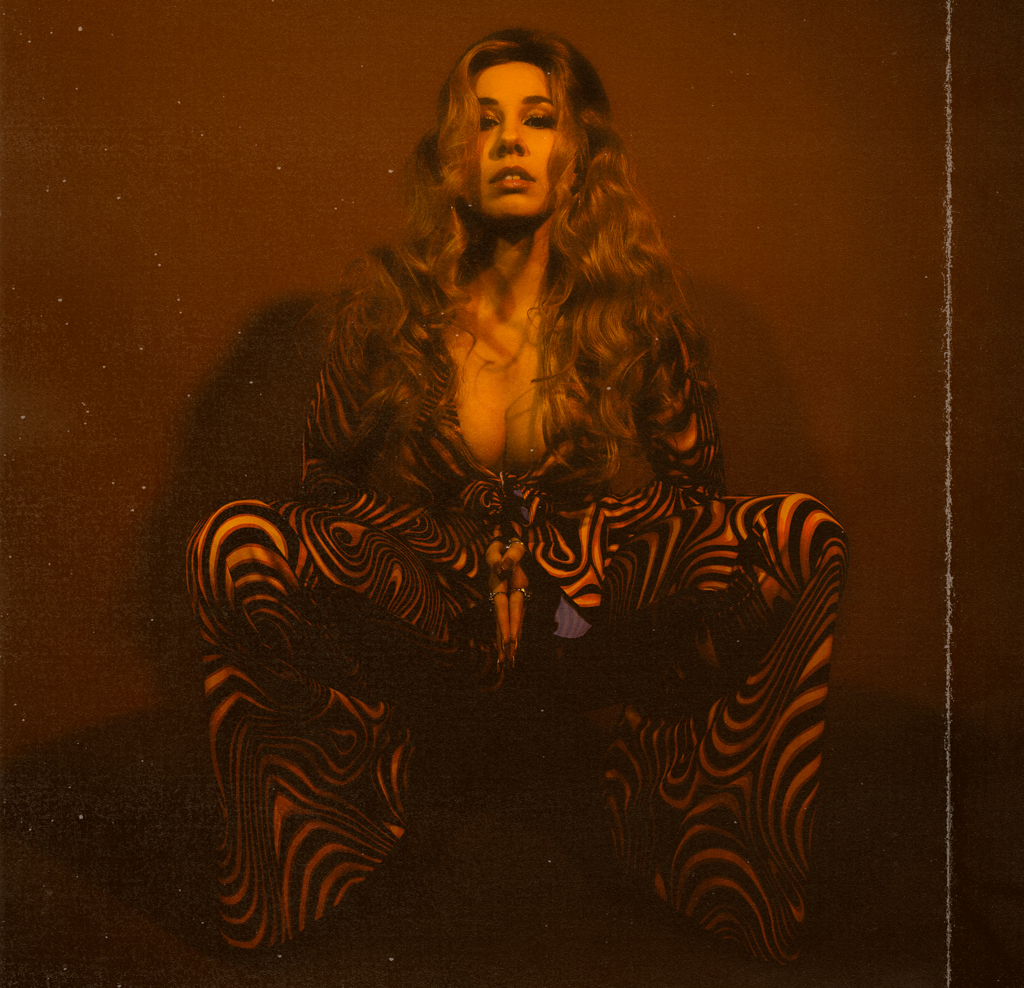

The Artist: Haley Reinhart (Los Angeles, CA)

Many might know Haley Reinhart from her viral hit with Postmodern Jukebox—a vintage take on the Radiohead original “Creep” which has amassed over 60 million views on Youtube and counting. For others, Haley has left a lasting impact from her first rise to prominence on Season 10’s American Idol. Her 4th studio album entitled Lo-Fi Soul presents 13 tracks of original music featuring collaborations with multiple award-winning producers such as Rob Kleiner and Tony Esterly. Debuting at the Top of iTunes’ Alternative chart, Lo-Fi Soul is Haley’s first self-released album on the vinyl format.

Haley Reinhart’s Lo-Fi Soul album art. Photo by Dana Trippe.

Thanks so much for doing this, Haley! The timing of this article is perfect with the release of your album appropriately titled Lo-Fi Soul. Does the title have any personal meaning to you?

I really wanted to put a spin on what it means to be an old soul. Growing up, I’ve always been called that ever since I was an infant. At a young age, I would get up on stage with my parents’ band and I’d meet people who would say the same thing. I still hear it to this day. It’s something that’s been very intriguing to me and this album has given me an opportunity to do a lot of soul-searching and self-discovery.

As for “lo-fi,” I really love analog. I love the low fidelity graininess and rawness of the older generation of music. It represents me in the sense of being very vulnerable, real and raw.

The album perfectly encapsulates that. And to be collaborating with over six producers in this album, kudos to each of them for nailing the raw lo-fi vibe while still being true to your original sound.

I’m really grateful to be in a place in my career where I can get my message and sound across. You feel like you’ve paid your dues enough at this point to communicate exactly what you want and what you don’t want. I’ve grown to have great relationships with each producer over the years. The more you collaborate with them, the more comfortable you become. That’s why I feel like this album represents some of my truest work yet. This is my fourth album and I feel like I’ve finally gotten to a place where I’m being fully heard. Nobody’s telling me what to sing or what to write, which is a great thing.

You’re the boss this time.

I do feel it. It’s tough being anyone in the music industry, let alone be a younger woman. I’m sure you can completely relate to it, doing what you do. You kind of have to play the game for awhile and then you get to a point where you’re already writing 99% of the lyrics, melody and what have you. But now, you have to ask for the credit that you deserve.

Did you have a vinyl release in mind when you were conceptualizing the album?

Yeah, definitely. I’ve always wanted my records out on vinyl. My last album What’s That Sound? was released on vinyl through Concord Records because it was an homage to music from the late 1960s. But before that, I never got to do vinyl for two previous albums which were all originals. It’s always something I pushed for but I didn’t always get in return. So being able to do it on your own, you realize that it’s not just a dream anymore and that it’s doable.

How long have you been a vinyl record enthusiast?

I grew up in a cozy little home with my parents in Chicago—lined with wood panellings, tall loudspeakers installed on both ends of the house, and we had a record player, of course. My dad owns a brilliant eclectic vinyl collection so we’d be listening to vinyl 24/7. Through the holidays, he’d put on everything from Dean Martin and The Carpenters to Led Zeppelin and Carly Simon, along with the occasional Christmas tunes. We’d listen to The Beatles for days. So in a way, I was actually born into that sound.

Last Christmas, I didn’t ask my dad for anything except for some vinyl records he was willing to part with. I’ve had some cool experience with those vinyls he’s sent since then—like getting his Crosby, Stills and Nash record signed by Steven Stills, and The Doors record signed as well by Robby Krieger who was one of my dad’s icons because he was a shredder.

So you’re dad is living his best life right now!

I wish they were here in LA all the time, but I’ve gotten both my parents to sing and play on stage at the Troubadour. My dad got to play with Robby Krieger and we did “Light My Fire.” So in a way, I’m trying to simultaneously make my parents’ dreams come true. They deserve it.

Props to your parents for instilling their love for music through you. You can tell that your parents played an influential part in that “old school soul” sound. Speaking of old school, what do you think is the reason for vinyl’s huge comeback?

In general, when I think of music back then, I think of good music that has integrity and the potential for longevity. And for today’s listeners, I think that they’ve been away from it for a good decent amount of time. People are ready, and are anxiously in need of having something tangible like vinyl records again.

And you can’t deny the warm sound. You can’t really put a stamp on what music is and qualify one sound as being okay for everyone, but I do think people are ready again to go back in time and live the simpler way of just being able to hold music in their hands—to be able to touch a record and hear something that sounds super warm on their loudspeakers.

I agree. Music isn’t meant to be complicated. You just drop the needle on the turntable and appreciate the music for what it is.

Right. But after what you showed me about the vinyl cutting process—seeing you cut a 45—I realized how complex the art of mastering for vinyl is. Many people take it for granted. Many of us wouldn’t even know how vinyls are made or how it could work in the first place. It just puts it even more into perspective how lucky we are to be able to utilize that sound.

Being at the final stages of getting your vinyl release out for mass distribution, has there been any unexpected challenges along the way?

Narrowing down the song list so the album fits on a 12” LP was really hard. At this point, I don’t know how people are going to react to what they really like on vinyl so it was hard for me to take off 2 songs from the vinyl release. I’m happy to have worked with you because I know that between you and Furnace, I know that you all care for the utmost quality of the sound and you don’t want to compromise that. At the end of the day, I have to make these decisions. The quality of the record is our top priority.

Another unexpected challenge was the actual packaging itself, you’d have to remap the liner notes because there’s obviously not as many panels compared to a CD. It was a challenge having to take all the “thank you’s“ from different photo panels and putting them into one. We’ve figured it out, but it was definitely something that I forgot about in the beginning.

Self-releasing on vinyl for the first time is always daunting, but you now have all this experience under your belt which will prepare you for the next album release down the road. It’s empowering to have control over these moving parts yourself.

You’re absolutely right. I have my moments where I feel completely overwhelmed. I’m at the finish line now so I’m taking a deep breath and calming myself down, telling myself, “Hey, you’re learning all these new things at a vast rate. It’s only gonna help better prepare you for the next time around.”

And it’s been rewarding, beyond anything that I’ve ever done in the past. So I already feel the pride. The vinyl release is not out yet but I’m starting to relax a little bit more. The work is done, I can sit back and be happy that I did it. And now I just know I can do it. Anybody could if they really wanted to.

You’ve often said you’re not as well-versed with technology but despite that, you were able to stay immaculately organized through the whole process. Props to you on that.

Thank you! There’s a lot of things that can slip through the cracks, even with labels (you know how it goes). I blame my Virgo nature here, for better or for worse. I had to get so much lined up—from the lyrics and the panelling down to getting every individual songwriter and producer’s publishing information listed on every track. I even had to track down some songs I wrote 7 years ago. So I really appreciate you for saying that because I tried to make it as straightforward for people to process as possible.

Haley Reinhart’s Lo-Fi Soul photo shoot. Photo by Dana Trippe.

As an artist, what advice would you give for other independent artists who are considering releasing their own music on vinyl?

I would say, when releasing music on vinyl, remember that it has to be totally authentic and original to you—something you know you’ll be proud of for years to come. Because a part of having a piece of vinyl is knowing that it’s something that has the potential to live on for generations. You want to be able to look back and know that you made music that you would be proud of and never regret. So the artist needs to be unabashedly themselves—not compromise themselves too much for the millions of other cooks in the kitchen.

Though we can all agree on its physical longevity, do you think vinyl is also here to stay as a commercially viable product?

Definitely. Just an interesting side note—I recently flew to Vienna, Austria for a direct-to-vinyl performance of my song “Don’t Know How to Love You” with a 40-piece orchestra, shot at the historic Südbahnhotel (built in 1902). This was for an upcoming feature documentary shot entirely in 35mm film entitled An Impossible Project. Directed by Jens Meurer, the documentary tells the story and rebirth of Polaroid and the analog film.

Part of this documentary also involved a filmed discussion amongst 20 “digital superheroes” about the importance of analog versus digital. Being the only musician/artist on that table, I knew I had to speak up and hold my own as an artist. I spoke up several times supporting analog and vinyl. As much as I know that digital has its benefits, I also think the validity of analog will always remain relevant. And I think the same goes for vinyl. It’s like any true polar opposites that you could think of—the existence of one complements the other and brings balance to life in general. So I do believe vinyl/analog is just as important in the digital age.