6 Tips for Recording Interviews in the Field

Recording interviews in the field for radio and podcasts is a great way to hone your craft and earn money. Here are six tips to help.

Recently, I stepped away from my mixing duties to report a piece for WHYY, an NPR station based out of Philadelphia. The gig got me out of the studio, recording interviews in a variety of locations, and dusting off a bag of in-the-field tricks that might be of some benefit to you.

If this sort of work intrigues you—interviewing people in the field for radio and podcasts and the like—read on. We’ll cover the right tools for the job and some good techniques for getting a quality sound.

What is a tape sync?

If you listen to talk radio like NPR, podcasts from outlets like Gimlet, and similar fare, you’ve heard the results of a tape sync: It sounds like two people sitting down in the same room for an interview. This is but an illusion: the interviews have been recorded in different locations, only to be spliced together later to sound like a congenial tete-a-tete. Often the host sits in a studio, recording their end of the interview as they hold a phone to their ear. At the same time, the guest sits elsewhere (their house, a library, or some other location), talking to the host over the phone.

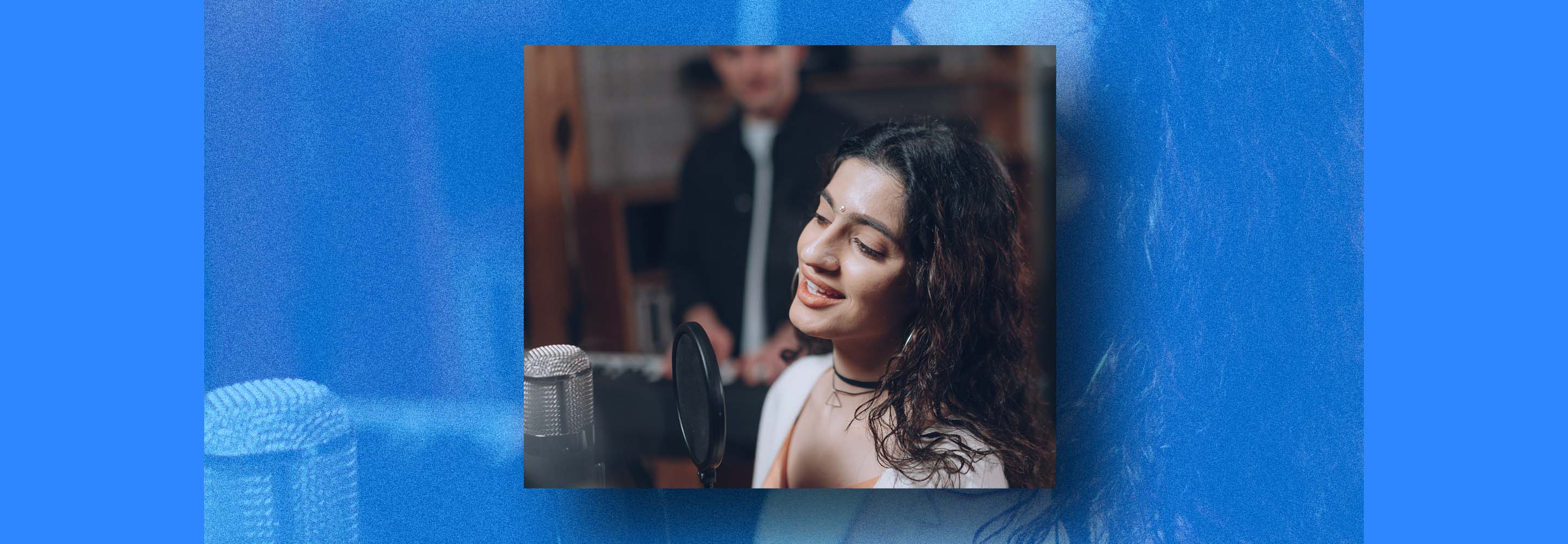

Here’s where you come in: you, the recording engineer, have traveled to the guest’s locale. You capture the audio on their end. You hold a shotgun mic to their face, or you ensure they talk correctly into a mic situated on a desktop stand, all while monitoring the levels, angling the mic for the best sound, and interjecting if things get too noisy.

This is a tape sync (also called a phone sync, a double ender, a simul-rec, and some other hyphenates that sound equally confusing). Let’s cover what you’ll need to do one.

1. Tools needed for a tape sync

If you’re the owner of a Spire Studio, you already have a tool that can be used, in a pinch, for tape-syncs. It can come in handy while you’re first getting your feet wet in the game. Later on, when you’ve chosen to purchase a dedicated recorder for this sort of work, the Spire can be your backup recorder in times of limited battery life or unexpected malfunctions. A real engineer knows that the difference between an amateur and a pro often lies in the backups!

Whether you’re recording your own interviews or diving into the tape-sync world, you should have the following on hand:

- A good, rugged microphone (often a shotgun mic)

- A backup microphone (even a Shure SM57b can work for backup)

- A tabletop mic stand if you’re setting the mic up, or a pistol grip if you’re not.

- A windscreen or “furry” for each mic, location dependent.

- XLR cables (main and backup)

- A primary recorder

- A backup recorder

- An SD card with plenty of memory for the recorder

- Extra batteries

- A laptop, if your gig is same day delivery

- A backpack with plenty of padding for all your gear

- Good closed back headphones

As I pack an item into my backpack, I put a little check mark on the note-card. I check off each item again as I repack for the trip back home. This ensures I don’t lose anything, and is a great habit to form for any recording session.

As to the microphone, often a shotgun is employed—many people I know carry a Rode NTG2. People like shotguns for their directionality and form-factor: you can get in close and mitigate sound coming from off-axis places. Still, given the right location, some people prefer other microphones. Lots of NYC engineers use an EV RE20 or a Shure SM7b. These are pretty common mics and a lot of engineers already have them. Perhaps you do, and thus already have a great capsule for the tape sync.

The recorder and the backup recorder combo are most important, should something go absolutely wrong. You don’t want to be in a position where the whole interview falls apart because of your gear.

You probably brought your Spire to accomplish some songwriting on the go with good results. But here’s the thing: The Spire has microphone preamps by Grace Designs—remarkably clean, quite clear, and perfect for the human voice. It also sports a respectable battery life and a convenient form factor. Wav file recording at broadcast-standard 48 kHz? Check.

Indeed, with a Spire Studio, I was able to get a tape sync that sounded like this:

Sounds like we’re in the same room on two different mics? Sure! But we weren’t in the same house. So, if you have a Spire, all of these factors make the unit great for testing the waters on a friend’s podcast or a student project.

Spire Studio is great as a primary or backup recorder, no matter where you are.

2. Get as much information from the producer as possible

Here’s how the job might go down: you see an advert for a tape-sync at 2:00 p.m. tomorrow in your area, and you apply for the job, citing your equipment and providing a CV or a reel (more on this later). The ad will tell you how much the job pays, whether it covers expenses, how long the interview lasts, and where the interview will take place.

If you’re selected, the producer will provide you with further details—the address, whether the interview is inside or outside, when you should start recording, and any special circumstances surrounding the guest. They’ll also tell you how they want the file recorded and delivered (sound format and file-transfer method), and how quickly they want it delivered.

Don’t forget to show up a little early to deal with any issues present at the location (fridge or AC noise, external traffic, et cetera). You can’t be late under any circumstances, or you will end up costing the studio a lot more money than your budget calls for.

3. Record the best possible vocal sound with proper mic placement

If you know how to record vocals in the studio, it’s not too hard to record vocals outside the studio. The basic rules apply: get the mic in closer and it will sound rich and full. A mic with a cardioid polar pattern will work better in a location you can’t anticipate. The directionality of the cardioid polar pattern will help you beat back unwanted sounds from the room (to some degree). The pattern will also help you use the proximity effect to greater, erm, effect.

Move the capsule a little farther away from the mouth and you may mitigate some p-pops. Move the mic slightly off axis and you may avoid some sibilance without too much sonic tradeoff.

Gain the preamp on your recorder incorrectly, and it might overload or distort. What you want is a good sound, loud enough to beat the noise floor if you’re recording 16-bit audio, but not too loud that it might clip. If you’re recording in 24-bit and the recorder has a decent noise floor, you don’t have to worry about filling the meters.

4. Be aware of your recording environment

Keep a keen ear on the environment too. If you’re hearing a weird response from the vocals due to a glass surface behind the speaker, or some other room anomaly, try to fix this as best you can by moving to the other side of the guest so they face a different direction. While you’re setting up, you’ll have your headphones on, plugged into the record, listening to the room—this will give you an idea of what you’re up against.

Of course, you’re going to need the subject to say something as you’re setting up, to get a feel for their voice and your mic. “Sing at your loudest please” isn’t going to work here. I tend to ask people their name and the last thing they found interesting. That way, people are a little more animated in their responses, so you can get a better idea of their levels.

Most if not all tape syncs occur outside a studio environment, so you might hear sounds coming from other rooms, sirens coming from the outside world, or a whole host of other unpleasant noises. There’s nothing wrong with interjecting during the interview and saying “hold for siren on our end,” followed by, “repeat the question please!” This is appreciated by all involved.

5. Capture room or ambient tone

Room tone is important; it lets the editor stitch the interview together in a way that sounds more natural. It’s not uncommon for an hour-long interview to be edited down significantly, and one way to make the cuts work is to use room-tone as a noise bed.

At the end of the interview, record one full minute of silence. Just say “I need a moment of silence for room tone”, and hold the mic up exactly where you had it before. It’s as simple of that, and the editors will thank you when removing background noise, an easy task with RX.

6. Label and organize your audio without editing

To make the editor’s life even easier, you can label the audio files before sending. Put the name of the show, the name of the interviewee, and the date. Denote the room tone file as "room tone" so you don’t scare the editor if they open that first!

You can ask the producer about the naming conventions they prefer during the initial phone calls. They may tell you the engineer will have the info, or even not to worry about it. Still, it pays to be organized—and it looks good too.

If you’re at all quality conscious, you’ll feel a desire to edit your audio—maybe even RX it for noise control. Don’t do this. The audio needs to sync perfectly, and you may be making more trouble for the show with your edits. Also, the mixer will probably have their own noise-reduction tools—more often than not it’s RX. Let them handle it, as they have a better idea of the atmosphere needed for the finalized mix.

If you’re aware of some glaring, unavoidable issues, you can always drop the team a note saying what they are and where they occur.

So how do you get an interview or tape sync gig?

I found my way into this sort of work by accident, and I think unless you go to school for this sort of thing, you might have to wait for your own accident as well. However, I can give you these words of encouragement from experience: the community is open and kind enough to provide you with such a lead if you go looking for one.

Ask around: see if someone might need an interview recorded remotely. All you need is one or two solid examples for your reel. This, combined with a good gear list, can get your foot in the door.