Why Do My Mixes Sound Bad? 8 Tips to Douse the Flames

You have only so much time to mix, but no matter what happens, everything sounds bad in your room and in your cans. We’ll cover some ways to get yourself out of this frustrating situation.

This article references previous versions of Ozone. Learn about the latest Ozone and its powerful new features like Master Rebalance, Low End Focus, and improved Tonal Balance Control by clicking here.

I wrote an article a while in which I covered what to do when you find yourself in an inevitable mix rut. It detailed ways to pick yourself up and dust yourself off. Think of this piece as its spiritual sequel, one covering an even more frightening, and sometimes, downright shameful phenomenon: that moment when nothing coming out of your system sounds good.

You know what I’m talking about. You switch on your system, you sit down to mix, and everything sounds god awful. Is it your monitors? Your headphones? Your ears? Is it somehow everything?

It just might be. And furthermore, you might have a deadline. Taking a break isn’t an option.

If this has happened to you, don’t worry—it’s happened to us all. That’s why we’ve compiled a list of ways to overcome this moment. Some of them are practical, some of them are psychological, but all of them will help.

1. Make sure something isn’t actually wrong

First, make sure something isn’t actually amiss with your gear. Many are the times where it hasn’t actually been my ears. With a panoply of hardware pieces and software abounding, it’s easy to see where something might mangle the proceedings in the chain.

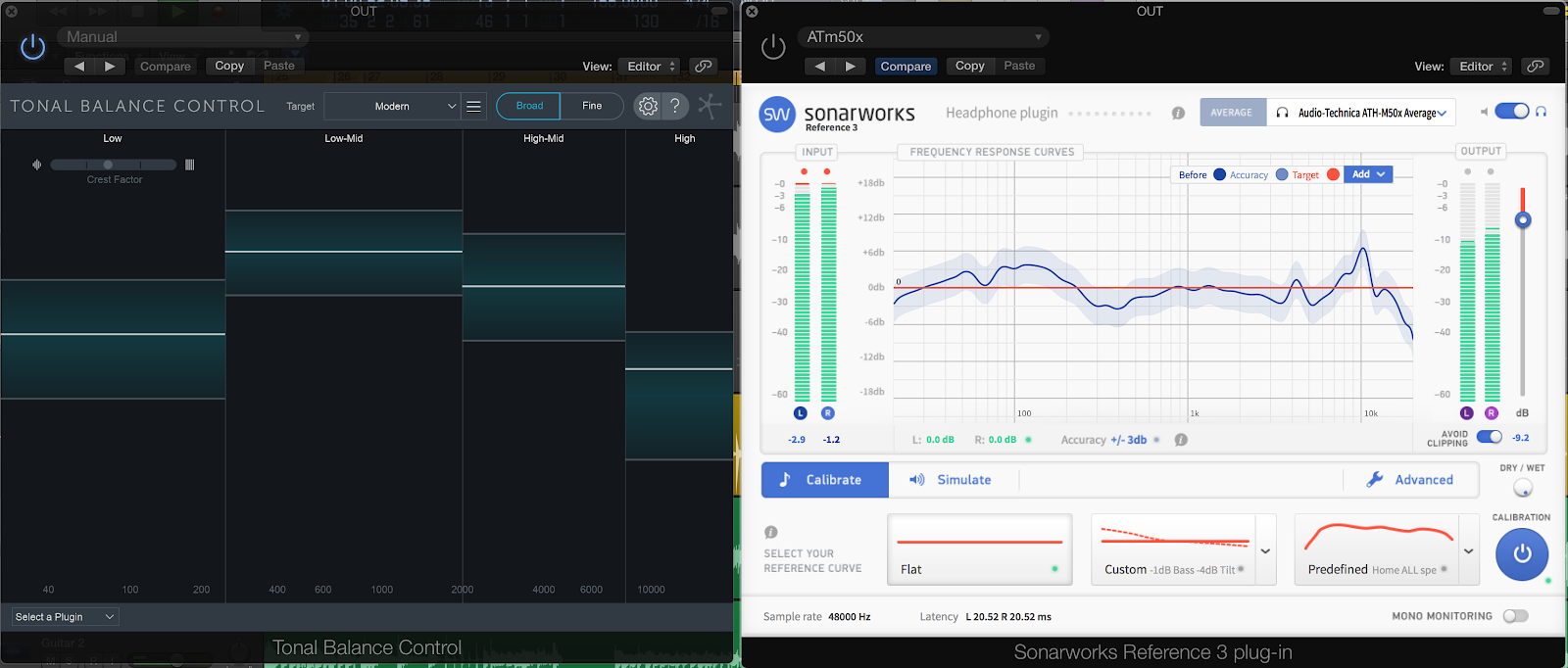

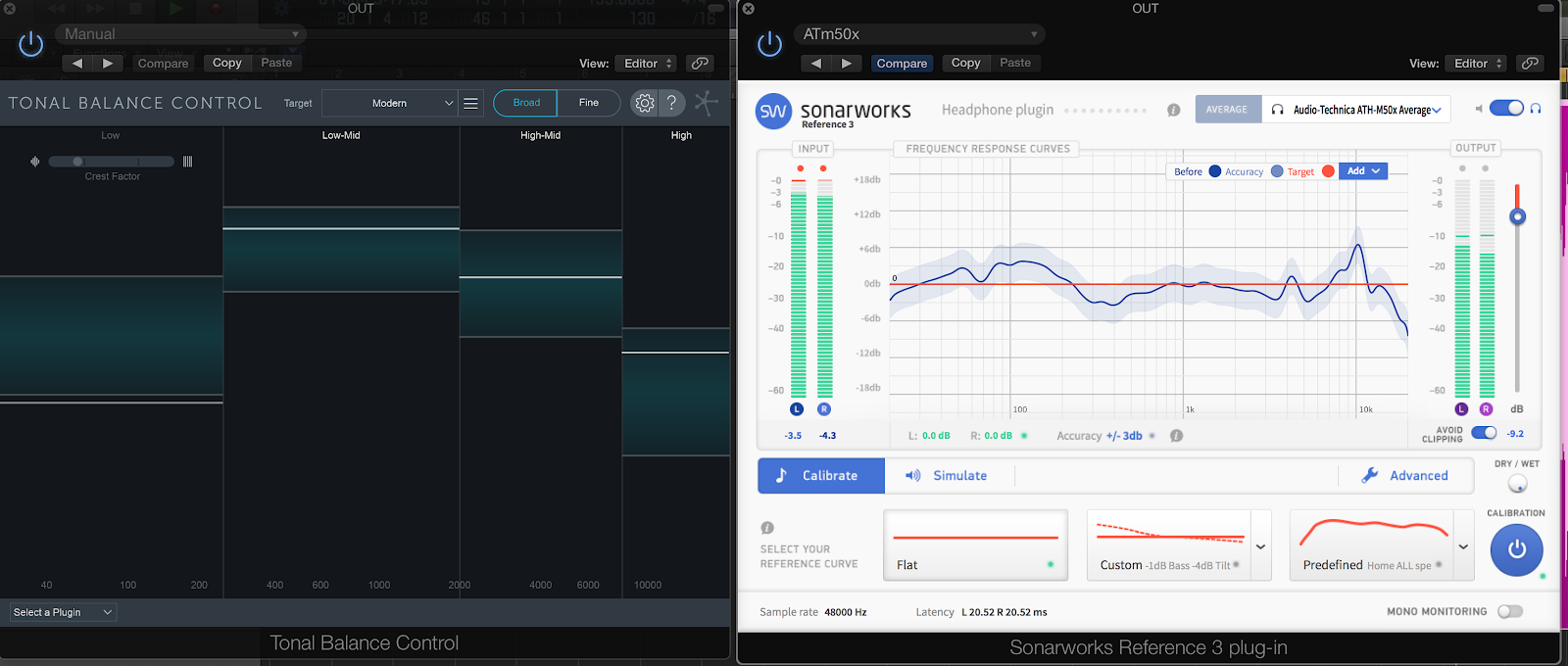

Do you use headphone correction software like Sonarworks? Perhaps you’ve inadvertently switched the frequency profile to an earlier variant of your studio setup. Do you run more than one hardware device and sync from an external clock? Make sure to check your sync source is what you need it to be. Power issues can also have subtle effects on the sonic quality of your rig. In my new home studio, everything felt a bit “off” until I went out and got a Furman power conditioner with noise filtration that protects against RFI, EMI, etc.

I’d wager to say that nine times out of ten if you’re just getting started mixing and something sounds palpably off, something probably is off—and it’s likely an easy fix. Go through a checklist and see.

In the screenshots below, we use Tonal Balance Control to illustrate just how much a plug-in like Sonarworks can affect your mix.

Tonal Balance Control with Sonarworks bypassed

Tonal Balance Control after Sonarworks

2. Make sure nothing has changed in the physical space

This is a corollary to the previous point, and perhaps a bit obvious, but when you’re in the thick of it, an obvious answer can sometimes solve the problem. Ask yourself this basic question: has something changed in your room?

Did you recently change or swap out any furniture? Did you leave a normally closed, quite heavy curtain open, exposing the surface of the window? Did you purchase new room treatment, hang it up, and totally forget about it? (Hey, it can happen!)

The room has a huge effect on what you hear coming out of the speakers, and if things sound off, it’s possible something in the room is significantly out of place. Heck, I once mixed in a room that was so small, and so weirdly shaped, that removing a large stack of cardboard boxes in the corner drastically changed what I was hearing. What did I do, you might ask? I put the cardboard boxes back.

3. Take five deep breaths

Okay Nick, what the heck is this new-agey advice doing in a list of practical tips? Well, chances are high that you’re stressed beyond belief by the situation. You’ve got a deadline, everything sounds off, you’ve done your due diagnostic diligence, but no, it’s your ears.

So this is the situation. And you better accept it now: acceptance is the answer to all of these problems today; remember that this too shall pass.

One way to get yourself to a place of acceptance is to take some time to breathe. Five centering breaths should do the trick. In this time, do not think about anything in particular—especially the mix. Your job, for the next five breaths, is just to breathe. At first it’s surprisingly difficult (there’s mixing to do!), but after the fifth breath, you’ll be in a better position to make a smart choice, instead of a seat-of-the-pants move that ruins your mix. Again, this might look like the least helpful trick in the tutorial. Believe me, it’s the opposite: this is the best thing you can do to bring your balance back.

Once you’re collected, you can move into some concrete tips:

4. Switch to another reliable source of monitoring

Sometimes a change in venue can help, inspiring you because of the innate difference of the sound. Your monitors and normal cans are out, but if you’ve got a second set of headphones you trust—hopefully over-ear, flat response cans with a 20 Hz to 20 kHz range—now is the time to break them out, just to shake up the routine.

Put them on and switch over to your reference tracks. Get yourself acclimated to your new monitoring environment for the time being. Note what sounds different, what sounds the same, and keep this in mind.

Now, switch back and forth between the references and your mix. Try to identify sold, concrete things that’ll get you back in the ballpark. See if you can limit it to five issues and under, and try to set aside problems like automation or granular detail.

Instead, hit the broad strokes. Is there an issue with the snare drum? Is it the level of the vocal? Or is it something global, like the lack of excitement in the upper midrange? Whatever it is, note it down, and try to get to work.

If you find you’re still banging your head against the wall, move on to the next tip.

5. Try mixing in mono for a while

This tip works particularly well if you’ve already handled the level and panning arrangements earlier, and find your ear-affliction cropping up upon returning to the mix after a break.

Try folding the mix into mono and working to make that sound the best you can. Sometimes, it even pays to switch one of the speakers off for the full mono experience, positioning yourself in front of the operating speaker, and making slow, deliberate choices based off your single speaker.

Mix in mono in Ozone 8

Monitoring your mix in mono can reveal issues with phase and frequency masking that wouldn't normally be apparent when separated into stereo L/R. It’s also been postulated that mono listening can help prevent ear fatigue, or that mono listening forces you to really home in on the frequency choices that matter. I’ll leave the explanation to the scientists, and only remind you to keep this tool in the box.

6. Try something crazy—but save a new file

Along the same path as the previous tip, try to shake things up by executing a move you’d never normally do. Never mix in to bus compressors? Now’s the time to give that a go. The reverse is also true: take everything off the master buss and see where that gets you. Do you have a careful approach to EQing, going for small decibel boosts and cuts? Let’s throw that out the window and make some huge, drastic choices.

Many times, fear can put us in this particular rut. In the face of fear, it helps to do something that makes you fearful, something like messing up your mix with broad, intentional strokes you’d never think to try. There is a caveat, however:

Always save this version as a new file. Clearly label it as different from the previous mix, so that you don’t do harm to the original copy. If you realize that certain elements of this new mix work while others don’t, you can import them selectively into your old mix, provided your DAW allows you to do that (Logic Pro X and Pro Tools both should).

7. Invite someone into the space

If even your reference tracks sound off, that’s a big clue that either your system is out of whack or your ears are playing tricks on you. One way to recalibrate your ears can often involve inviting someone into the room for a listen, preferably someone who isn’t an engineer. Just a run of the mill civilian will do.

This is why, sometimes, it pays to have a roommate. Heck, even better if they’re a spouse or a partner—then they might just feel obligated to help you due to the constraints of your relationship (please note: while iZotope can give you tutorials on any number of topics, iZotope cannot provide relationship advice).

Whoever the person is, have them come into the room and sit in your mix position. Sit next to them, nearby, and play some snippets of a reference tune. After a few moments, ask them how it sounds. Don’t ask them if it sounds weird; just ask how it sounds.

Sometimes, a funny thing might happen: you won’t have to ask. Sometimes you’ll find your ears resetting to the room as you watch your friend groove to the music, as though nothing at all is wrong, because nothing in fact is.

Play them a tune you know they’ve heard—play them their favorite tune, if you can. If it does sound weird to them, that may be an indication that something actually is wrong with the environment.

8. If even the references sound bad, make everything sound as bad as the references

This is your penultimate tip, combining psychological mind-games with practical considerations.

If even your references continue to sound horrible to you in this moment, then shift your thinking and try to make your mix sound as bad as the references. Match the harshness hertz for hertz. Make your mix as squashed-sounding as the references.

The thinking behind this one is simple: the references, selected by you/your client in a time of better judgment, are proven to work. They are proven to be what you need them to be. So if you make your work sound like their work, even if you don’t like how it sounds, you’re probably not going down the wrong path.

A great way to make an accurate judgement in this way is to use Tonal Balance Control and create a custom curve from your reference track. You can then visually identify where the harshness or mudiness may be happening and make quick decisions to conform your mix to that reference. In a pinch, you can also use the Match EQ feature in Ozone 8, which applies a target EQ curve to your track that is derived from your reference track.

Match EQ in Ozone

A caveat: only whip out this trick when time is of the essence. You can easily miss the small picture details—or risk making your tune feel lifeless in subservience to another mix—when trying to match in this circumstance. Here, you’re simply going about the proceedings as efficiently as possible because you have to, and this is the best psychological conditioning/practical tip for the moment.

Conclusion: Don’t expect everything to return to normal all at once

Our ninth and last tip is also our conclusion because it’s a good note to end on: during these ill-fitting times when the music doesn’t sound right, it’s so daunting; everything feels off, and we have no idea why.

Along the same physic tip as the breathing-centered one listed above, try to remember that your mojo may not come back to you all at once. It may gradually return, little by little until you don’t even realize that everything sounds okay again.

Just the other day, I experienced this: in the morning I was mastering a project, and I was in the flow. Every choice felt like the right one. But after a lunch break, nothing felt right. So I followed the list. I checked for malfunctions. I sat back and counted my breaths. I tried the cans. I tried sonar works for the first time in a few months, in order to change my monitoring situation a bit.

Next came mixing in mono, and finally, some go-for-broke choices. I can’t tell you when it all returned to normal, but at some point, my faculties returned, and I could go back to the full range monitoring system as per usual and make strong, deliberate choices.

The next day, upon playback in the car, on my earbuds, and within other venues, I was surprised by how much better I felt the second round came out that than the morning’s work.

Perhaps I had had to plateau before reaching new heights; that’s often the case in these matters, both for practicing musicians, and for us. In fact, if you view these frustrating moments as an opportunity to grow, it may actually benefit your abilities, rather than hamper your deadline.

So don’t be afraid when everything sounds terrible; treat it, instead, like the moment before something great happens. It often can be.