Noise Reduction Tips: When Does Noise Help or Harm a Mix

Noise reduction is a necessary part of making music. We consider the different types of noise in music production and how to make the call to keep or remove them.

From tire screeches to dog barks and public transit beeps, noise is a consistent fixture of the city soundscape. While these sounds tend to blend into the background of daily life, they are hard to ignore when captured by a microphone.

For this reason, noise reduction is a necessary part of making music. In a given session, we clean up hiss and rumble from home recordings, pull out clicks and pops from vocal performances, and dull pinging frequencies that poke out too far in the mix.

But we don’t always need to be so critical of noise. Since the beginning of recording history, it has been used to enhance instruments and even create new categories of music. Furthermore, too much noise reduction can strip a sound of its natural character.

To reflect this, we’ll look at the different types of noise common in audio and how to make the call to keep or remove them. While the tips will be from the perspective of music production, they are also applicable to post for film and TV.

Types of noise

There are many different kinds of noise that can disrupt music. If you can identify the type of noise it is, you will have an easier time picking an appropriate removal tool. Here are five noise categories and the RX modules to remedy them.

Impulse noises are short clicks and pops that vary in frequency and loudness throughout a recording. Mouth noises fall into this category and they are almost always removed due to their distracting quality. Some artists, however, deliberately include intermittent crackle and scratches in their music for a vintage effect or as part of a glitch sequence. RX Repair Assistant makes it easy to detect and eliminate clicks (as well as clipping, noise, and more).

Ambient noises

Ambient noises give us an impression of the space something was recorded in. They tend to be consistent in nature but it’s not uncommon for them to vary along with the music in a recording.

Ambient noise is categorized as tonal noise when it has a fundamental frequency and harmonics. When recording at home, it is common to pick up tonal humming from laptop motors and heaters in the 50–70 Hz range and sometimes higher. The De-hum module in RX identifies the base frequency and harmonics of electrical interference and removes it without pulling away desired parts of the signal.

When ambient noise is more spread throughout the spectrum it is considered broadband noise. Tape hiss, white noise, and other non-harmonic sounds fall into this category, and they are easily removed with the Spectral De-noise module. Follow our step-by-step guide to removing ambient noise with RX.

Intermittent noises

Intermittent noises are temporary sounds like coughs, footsteps, and phones rings that occur at unexpected times and clash with musical parts. Instead of doing an additional take, consider the Spectral Repair module. It allows you to select the intermittent noises in a recording and replace them with information from outside the selection. Learn more about Spectral Repair in the video below:

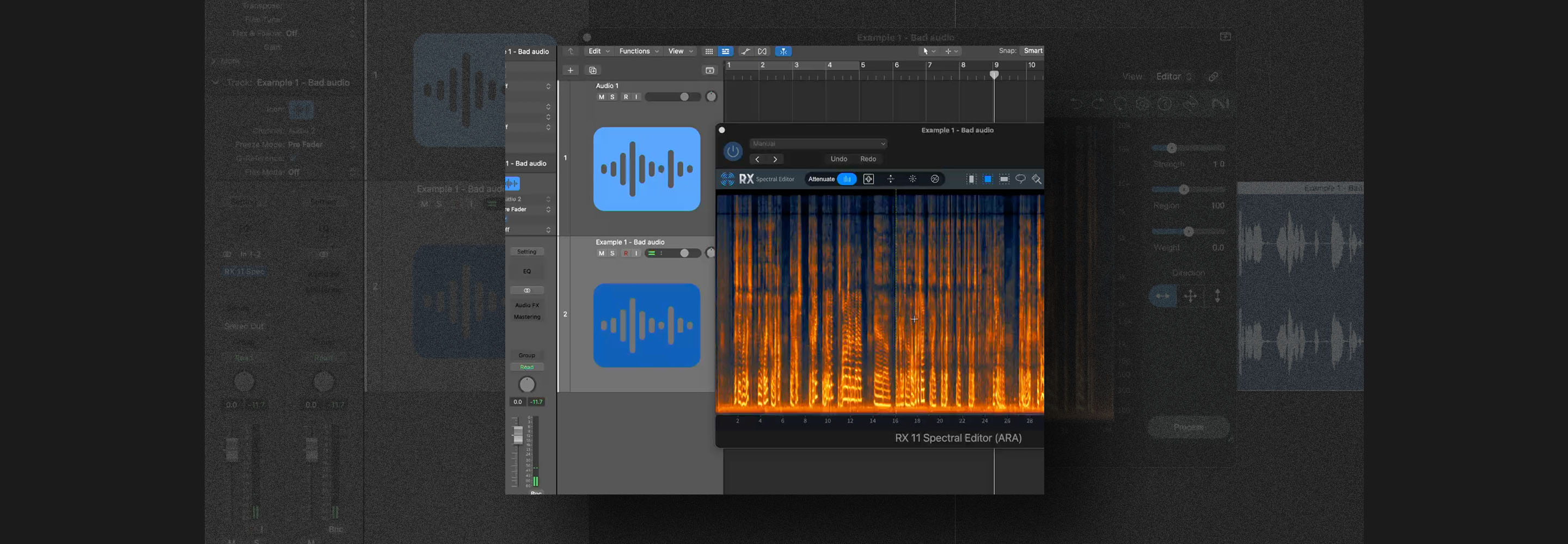

If you have trouble determining what kinds of noise are in a recording, or simply want to save time tracking noises down, we recommend using Repair Assistant in RX 7. It will scan a recording and suggest repairs to benefit audio quality. Watch this feature in action here or learn how to spot audio issues by eye in the RX spectrogram here.

When should you use noise reduction software?

In my experience, it can be quite difficult to produce a song with known noise issues dragging on the entire time. Outside of simply being annoying, certain noises can cause processors to act incorrectly. For example, a click at the tail end of a kick sample might trigger a compressor to reduce gain at the wrong time. Getting some of these issues out of the way early can clear the mind.

It is easy, however, to get caught up in editing tasks once they begin, so you may want to postpone long-winded noise reduction work until after the song is done to avoid wasting creative energy.

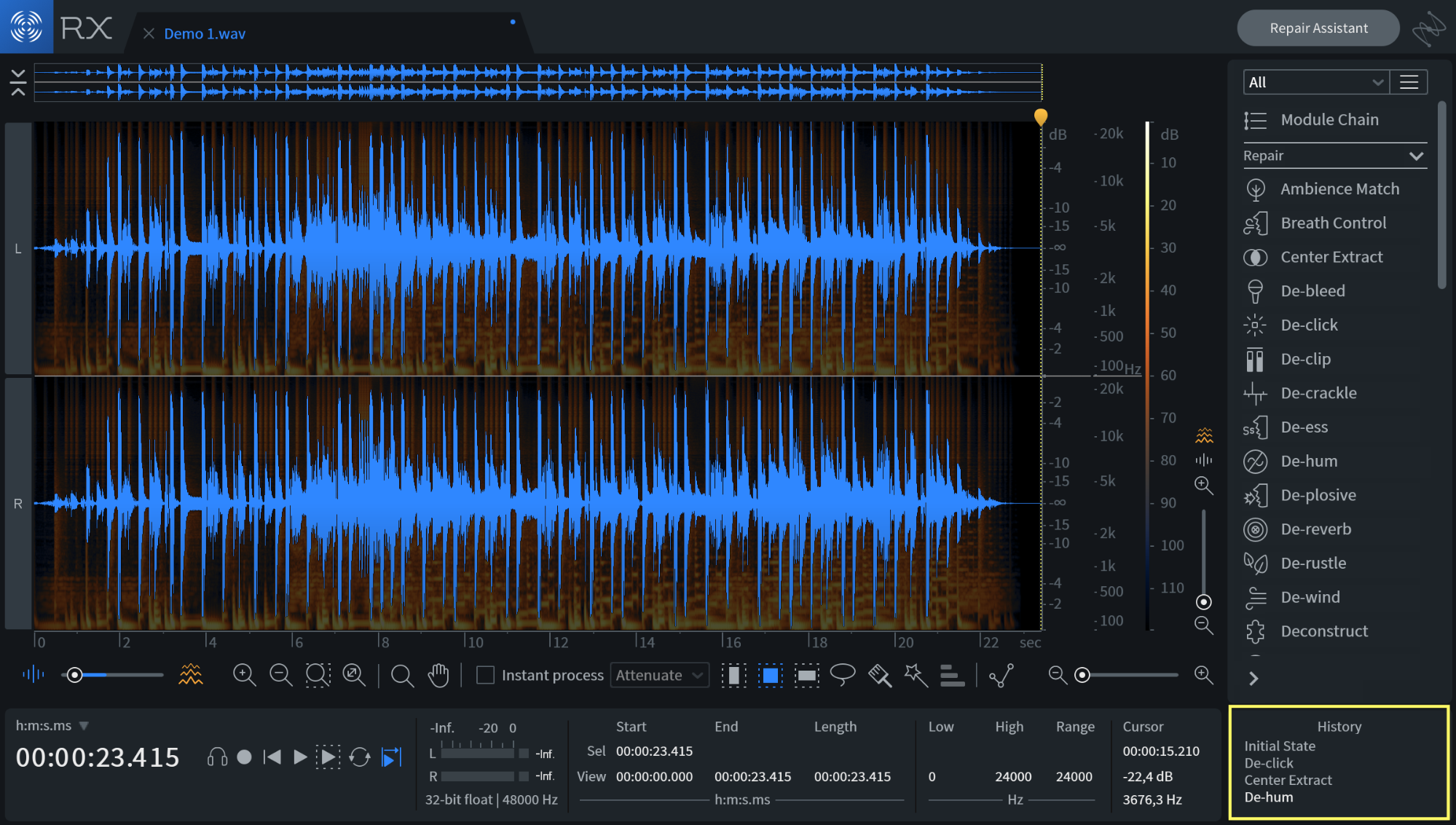

Pro tip: when printing audio in a DAW, the changes you make can’t always be reversed, and you may want to bring back some of the qualities you removed at a later stage in a mix. For this reason, RX 7 allows you to see a timeline of edits carried out in the “History” window and non-destructively revert back to earlier states.

Review audio repair history in RX

When to keep noise in

Does all noise need to be removed, all the time? Depending on the mood you want to establish, birds chirping, warm crackle, and even guitar squeaks can bring an intimate feel to the music that a clinical recording cannot. It is up to you to determine whether keeping noises in is appropriate for the song and if they pull attention away from the main musical parts.

It is possible to overuse noise reduction processing to the point of damaging sound quality or robbing a performance of its original character. Vocal breaths are one particular area of interest here. When you edit a solo vocal performance, breaths seem to stick out and you may be tempted to silence them all with Breath Control. But over an instrumental, a vocal performance without any breathing actually sounds pretty stiff and forced. You will want to turn down very loud breaths and edit out awkward ones, but otherwise, it’s OK to keep them in the mix as long as they don’t distract.

Introducing noise

There are situations where introducing noise into a mix will make it sound better. For a sense of groove and power, many of us producers rely on low-end thump, and while this is certainly not a bad idea, you may find it equally useful to double up MIDI synth lines and percussive elements with white noise to fill out the highs.

Tucking blended ambience into the background of a song is something I do often. Kept at a low level, where you just barely hear the noise, this bit of texture glues together the gaps between drum hits and other instruments. A trick once reserved for underground and lo-fi styles of music, the addition of faux noise is now embraced in pop production, as heard in Ariana Grande’s “thank u, next” and Travis Scott’s “Antidote.”

Placing a bit crusher, harmonic exciter, or full-on distortion plug-in (like Trash 2) on a submix channel or the master output will produce a similar “warming” effect by crisping up mids and highs with additional harmonics.

Staying focused with noise reduction

Noise reduction isn’t supposed to be heard as an effect and is considered an “invisible” process much like comping or vocal tuning. Repairing audio with RX 7 can make you feel like a magician fooling a crowd with impossible tricks, but this should not encourage you to show off and include some kind of aural wink to obvious noise reduction. Leave those kinds of displays to drum programming and melody writing.

Noise reduction tasks are also narrow in scope, involving lots of back and forth between processed and unprocessed sounds. For a big session, be sure to take breaks and reference your changes within the context of other instruments. What sounds noisy and disruptive on its own may very well be hidden behind a drum beat or bassline when once the tracks are brought up.

Conclusion

Depending on who you speak to in the music making process, you will get a very different definition of noise. For certain mixing and mastering engineers, it is a sworn enemy, while a rock guitarist might consider it crucial to their sonic signature.

Not all noise is bad, but there are certain unwanted sounds that can disrupt the music listening experience. In these situations, remember to listen, take your time, and set limits so you don’t overdo it with RX and remove more than what’s necessary.