Mastering Video Game Music: Celeste, Battlewake, and More

Explore how video game composers approach the art of scoring music for video games, then getting it mastered for a soundtrack release in digital or vinyl.

Video game music enhances our immersion in the world of a video game. And for many enthusiasts, this love for video game music extends beyond gaming itself. There has been an exponential growth in the demand for video game soundtracks—from streaming apps to vinyl records, all the way to live concert performances. And what better way for video game music to be heard than by making sure it’s delivered at its optimum quality thanks to solid mastering?

In this article, we hear from video game music composers about how they approach the art of scoring music for video games, and ultimately, how they tackle the challenge of mastering the music as a soundtrack for listeners to enjoy. We also learn how one particular video game track was mastered by walking you through its step-by-step process.

Mastering original video game music: Celeste OST by Lena Raine

Celeste (Original Video Game Soundtrack) composed by Lena Raine

One of 2018’s most highly acclaimed indie games, Celeste (by video game developers Matt Thorson and Noel Berry) is not only known for its unique and challenging gameplay, creative storyline, and character development—many of the awards it has reaped since its inception were thanks to the music written by composer Lena Raine. Lena is most notably known for winning the 2019 ASCAP Video Game Score of the Year for her work on Celeste. And since then, the Celeste soundtrack has gone on to be released in other forms, including a piano collection (with published sheet music) and licensed, jazz-themed lullabies.

Let’s dive into how Lena Raine produced the Celeste soundtrack—from writing and recording to mixing and mastering the music all on her own.

In a nutshell, how do you approach writing music for video games? Do you approach it differently than writing other types of music?

Lena Raine: I think the primary difference for me in writing something for a game—versus writing for anything else—is that for games, it really does depend on what the possibilities are for the audience: the person playing. Scoring a game requires you to provide the necessary materials for the player to get the impression that their actions are what is being scored, that their participation is meaningful in some way to how the score plays out. All the same building blocks of composition are there: good melodic writing, strong chord progressions, fun rhythms...but the actual structure and purpose of the writing ultimately comes down to scoring the experience.

Lena Raine, composer of Celeste’s Original Video Game Soundtrack

For Celeste's soundtrack, what was your strategy for mastering your own productions?

LR: From the start, it was primarily down to budget and experience. Because I am a fairly DIY composer, I don't really have a production crew, regular collaborators, etc. I was hired as a composer whose only experience was mixing and mastering her own music. Having someone else master the music wasn't something that even crossed my mind, since I'd dealt with the entirety of my music production from start to finish the majority of my career.

Ultimately, when I would master the tracks would come down to when I got final approval on something for the game. It was always one level's worth of cues at a time, since that was a good unit to work within in terms of making sure everything sounded good together. I worked in tandem with the developers, scoring each level as it was being designed, and so I would often master as I went, delivering as close to the final stem as I could. Of course, doing this meant that eventually everything felt a bit uneven, and so at the end of the project I went back and did one more final mastering pass on everything to make sure the levels, dynamics, and overall sound felt as uniform as possible across the entire game.

Can you name a particular track that you felt went through a transformation after mastering?

LR: It makes a lot of sense in hindsight, but since I worked on Celeste for a total of a year and a half, my own abilities and skills in mastering improved with each new cue I'd finish. It got to a point where I had to go back to the very first series of cues I'd written and mastered, and actually give them a second pass to bring them in line with my own new standards. Comparing the original mix of something like “First Steps” to its final version felt like such an absolute refresh.

While I don't have the original mix of “First Steps,” you can actually hear part of it in the first trailer we released [see video below]. It's also in a different key, with a different piano, and a far earlier attempt at mastering.

Before mastering: Lena Raine’s “First Steps” (original mix, before mastering):

After mastering: Lena Raine’s “First Steps” (final song, after mastering):

Mastering music from a VR game: Battlewake OST by Jeremy Nathan Tisser

Battlewake VR Game Original Soundtrack composed by Jeremy Nathan Tisser

One small subcategory of video games that’s experiencing rapid growth is VR (virtual reality), all thanks to the competitive virtual reality gaming market led by Playstation VR, HTC Vive, and Oculus VR. And paving the way for original, high-quality virtual reality games is Survios, an LA-based game developer that develops interactive VR games from the ground up. Back in 2017, their VR shooting game called Raw Data received wide acclaim after being the first VR game to break over $1million in sales in a single month. It has also received the coveted Game of the Year distinction at the 2017 AMD VR Awards. After the success of Raw Data comes another unique immersive game called Battlewake—a steampunk pirate-themed combat and PvP (player versus player) VR game that was released September 2019.

For the soundtrack of both VR games, Survios sought out the expertise of film, TV, and video game composer Jeremy Nathan Tisser. Besides Raw Data and Battlewake, his music can be heard on multiple VR games such as Zombies on the Holodeck, Wild Skies, and Tricklab, which garnered him the Best Mobile Game Score award at the 2013 Hollywood Music in Media Awards.

Let’s look into how Jeremy Nathan Tisser approaches music in the immersive world of VR gaming—from experiencing the VR game himself before writing begins, down to his thought process when collaborating with a mastering engineer for the game’s soundtrack release.

How do you approach writing music for VR games? Do you approach it differently than writing for other visual media, like film, TV, or non-VR video games?

Jeremy Nathan Tisser: I do indeed! Virtual reality is more about immersion, and the feeling one gets when being entirely thrust into a new world. It's awe-inspiring, not to mention completely mind-blowing! One thing I've noticed is that people tend not to notice the music in VR as much as they do in traditional gaming, but this has nothing to do with the quality of the work. It's simply because people are so taken aback and overwhelmed with emotion when they put the head-mounted display (HMD) on that the visuals tend to drown out the music. When I begin working on a VR game, the first thing I do is put on the HMD and experience the world I'll be scoring. It's that overwhelming feeling that I get that inspires my creativity and musical choices. I draw on that feeling to write the music, in the hopes that the music will then not only contribute, but completely enhance, that initial feeling when the consumer plays the game.

Jeremy Nathan Tisser, composer of Battlewake’s Original Video Game Soundtrack

When it's time for the soundtrack release, how do you go about folding down your music from immersive sound to stereo?

JNT: For my work in VR, I don't really get to write immersive music, but that is on purpose. Music is internalized. It's something we feel. We use it to get pumped for the gym, or keep us going on long runs or bicycle rides. We listen to music to pass the time. It's meant to make us feel things. In VR games, immersive sound is saved for things that belong in "the world" around you. If the music is immersive as well, it will feel like it's coming from the outside world, whereas I want the music to be internalized in the player, amping up their own intensity or heart-rate just the same as if they put headphones on to go work out. That being said, depending on the project, I would love to set up an Atmos system at my studio and write something crazy and intense utilizing ambisonics and full immersion.

Can you name a particular track that you felt went through a transformation due to mastering? How was it collaborating with a mastering engineer for your soundtrack release?

JNT: Chas Ferry was our mastering engineer on this one. He is Notefornote Music's main mastering engineer, as well as Varese Sarabande's. For me, track three on the upcoming soundtrack for Battlewake, titled "Into the Maelstrom," is the track that made my jaw drop the most. The track is sort of like a gypsy-punk band meets Pirates of the Caribbean orchestra type of thing. Now, I'm a really solid drum programmer, and I had a great mixing engineer on this track (Michael Bouska), but Chas did something to the track to make that kick drum pop after the fact. Chas took about two weeks or so and really honed in on the details of the soundtrack. I actually didn't have any notes for him because everything sounded just how I had envisioned it.

Below you can listen to "War at Urth's End," one of the tracks from the upcoming Battlewake OST release, before and after mastering:

Video game music on vinyl: Children of Termina by Rozen

Children of Termina album by Rozen, a Legend of Zelda “Majora’s Mask” tribute

As the demand for video game soundtracks continues to grow, so does the market for video game music on vinyl records. Video game vinyl releases are not only sought after for nostalgia. More importantly, the vinyl format is the driving force behind many creative interpretations of video game classics—from the music all the way to the elaborate vinyl packaging—as we’ll see from the featured artist below.

Daniel Jimenez, more popularly known as the artist Rozen, has a cult following for his unique take on many video game classics. Having released four video game albums to date on vinyl through renowned video game music label Materia Collective, his tribute albums for Legend of Zelda remain the most popular. Rozen’s latest album Children of Termina—a tribute to Legend of Zelda’s “Majora’s Mask”—has been awarded 2018 Best Album - Fan Arranged by VGMO’s Annual Game Music Awards. The album also debuted at the Billboard Top 10 under the Classical Albums category, a feat that’s not commonly achieved in the video game genre.

Let’s dive in and explore Rozen’s thought process as he creates his video game tribute albums, starting with conceptualizing the orchestration based on the original game music, all the way to collaborating with a mastering engineer for his music’s digital and vinyl album release.

Describe your thought process when arranging and orchestrating classic video game music for your tribute albums.

Rozen: I usually like to say this to people whenever they ask me, “Why do you arrange video game music?" It's because most of this video game music that I enjoyed growing up was from the 90's—Nintendo 64, mainly. Take the Legend of Zelda series, for example. While it's very nostalgic to listen to the original pieces, they're just not as enjoyable outside a video game setting.

So that's my goal when I'm trying to arrange these pieces, especially for Children of Termina, because I know I'm a fan first, then a producer second. I even try to find moments where I can throw in easter eggs and hide classic melodies that listeners can discover on their own as they listen to the album.

Not all Easter eggs have been found yet, which is very exciting because every now and then I’d still get messages from fans whenever they find a new discovery.

When writing/producing Children of Termina, did you have any concerns about how it would translate to vinyl? Having released multiple LPs, you're most definitely aware of the quirks of the vinyl format.

R: Back when I released my first album, Sins of Hyrule, I used to be concerned with how my music would translate on vinyl because I've heard other music in this format—soundtracks especially—and many of them sounded very muddy and not as enjoyable. You would hear a lot of oscillation and modulation, especially from the high string pads.

I did remember that being a concern, so I tried to use that in my favor. I approached my first album by making it sound a little bit more vintage. That’s also why I used synths with the strings in all my orchestrations—synths with the brass, synths with the percussion—so at least this whole album would sound "vinyl" and "vintage" to begin with.

But here's the thing: the vinyl lacquer masters were cut so well that it translated my music exceptionally well on the vinyl format. It sounds so transparent. If anything, it just adds a little bit of that warmth but it doesn't really change the experience, which is the most important part to me. So it’s not an issue anymore.

I also enjoy thoughtfully planning the concept of my album, and not just musically. A lot of people make fun of me for this, but even before I start writing the first note, I already know the album title. I already have the album art in mind. I already have a track list. It drives the music and it also serves as my inspiration.

Even for my vinyl releases, I would divide the album into big sections and acts from the get-go so I don't have to compromise my music for the vinyl release. So I would suggest for every artist out there who knows that they're pressing into vinyl to consider this from the conception of the album. It really helps.

Rozen, composer of Children of Termina (Legend of Zelda’s “Majora’s Mark” tribute album)

A mastering walkthrough: “The World That Ends in Three Days” by Rozen

Admittedly, the world of video game music is so vast and diverse that a mastering example of one song alone won’t be enough to fully grasp the depth of this genre. But it only takes one step to get you moving towards the goal of mastering video game music. From here on, the possibilities are endless, as long as you’re not afraid to experiment. One thing to keep in mind, however, is that critical listening and restraint will always be your friend throughout this mastering journey, as we’ll see in the example below.

Step 1: Listen to the music

Before establishing a plan of attack, always begin the mastering session by listening to the music in an accurate listening environment, giving it your full, undivided attention. Listen to this premaster audio clip of Rozen’s “The World That Ends in Three Days”:

Take the time to discern its unique characteristics and nuances. For this song, Rozen expertly crafted a lush production that featured a rhythmic, pulsating string section, a soaring vocal line, and powerful percussion. I wanted to make sure we didn’t lose this depth and energy in the production as it passed through the mastering stage. With this in mind, I then proceeded with my first mastering adjustment for this session.

Step 2: Apply the necessary amount of gain and EQ

For this particular song, I focused on the overall tonal balance, readjusting the EQ so that we feel more of the warmth and articulation in the bottom end. I found that this EQ adjustment also complemented the music by bringing the driving energy of the percussion ever-so-slightly more to the forefront.

Using Ozone 9’s EQ, I applied a 1.3 dB boost around 130 Hz with a wide Band Shelf filter shape, supporting it with a 1 dB Analog Low Shelf boost around 30 Hz. This might seem minimal, but in the mastering world this is quite a substantial low end boost, which I found adequately complements the tonal balance of the music overall.

Ozone 9 EQ

To optimize the gain-staging on my chain, I added gain using our studio’s analog tube line amp prior to re-entering the digital domain of our mastering DAW. You can also boost the levels of your mastering chain using plug-ins such as the Ozone 9 Maximizer.

Step 3: Pay attention to the dynamics and other particular nuances in the music

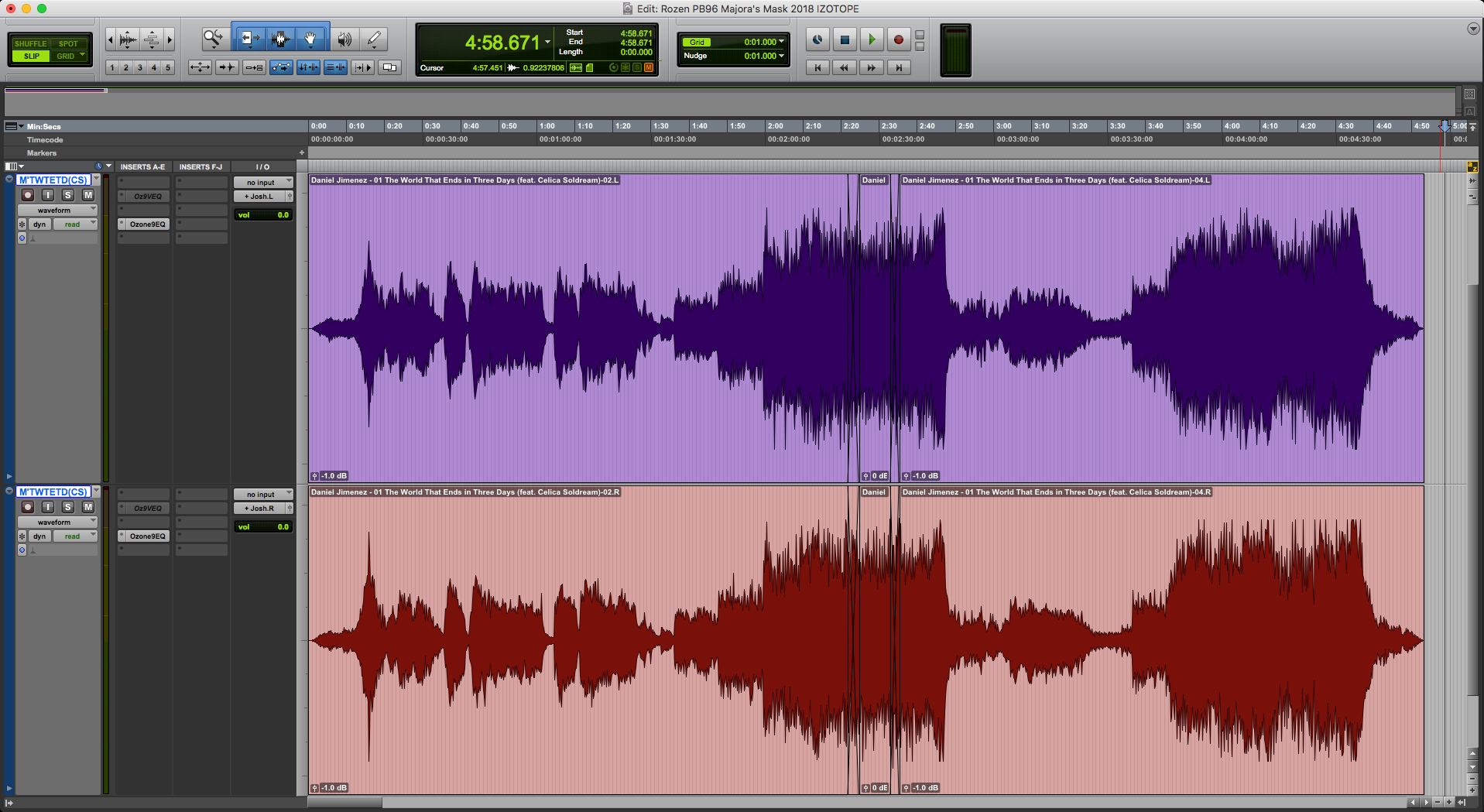

For this session, I wanted to make sure the song’s natural build-up is not compromised in the mastering stage, so I avoided applying any compression in the chain. As Jonathan Wyner mentioned in his “Are You Listening?” episode on Compression, not every song needs it. Instead, I opted for a more transparent option—clip gain. Gain ride works equally well if done thoughtfully. This allows for a smoother dynamic build-up without compromising the depth and individual transients in the mix.

Our track in Logic

Step 4: Fine-tune your limiting settings

For the limiting stage, I took advantage of the Ozone 9 Maximizer’s versatile settings to ensure that the wide dynamic range and transients in the original mix translate as transparently as possible after mastering. I opted for the IRC III Mode with the style set to pumping. This takes advantage of the mode’s aggressive limiting algorithm along with the Pumping style’s slower release speed, which complements this music particularly well.

Ozone 9 Maximizer

Listen to an audio clip of the original and final master of “The World That Ends in Three Days” below:

Conclusion

If you’re entering the wide world of video game music, learn from the masters (pun intended) and explore the endless possibilities that come with this unique medium. Take your time getting to know the game you’re working with, consciously listen to the music you’re mastering, apply your settings while keeping the nuances of your music in mind, and fine-tune for a master that translates.