Designing a Sonic Universe with Echoic Audio: Part 3

In part two of our series, Gus Nisbet of Echoic Audio shares how to use sound design as a musical element, why small details matter, and the power of ‘less is more.’

Gus Nisbet is a guest contributor from Echoic Audio, an award-winning music and sound design studio working across advertisements, film, and art. Based in Bristol, UK, Echoic’s engineers are specialists in music production and sound design, whose clients include Nike, Adidas, Dyson, ITV, Mercedes and Jaguar.

For the third installment in our series on how to design a sonic universe, we’re focusing on the relationship between sound design and music composition. Often, these two are produced separately and then mixed during the final stages of production. And this works fine. But the world of professional audio rarely settles for fine—it’s a competitive industry where the most successful and talented producers succeed by turning ‘fine’ audio into ‘fantastic’ audio.

Focus on detail, not complexity

One of the keys to creating fantastic audio is focusing on the details, the nitty-gritty. This doesn’t mean producing layer upon layer of complex music and sound design separately, this means ensuring every small decision is calculated—it must have an important, defined role within the sonic universe. The outcome? The sound design and music score will work together seamlessly.

We recently produced the soundtrack for a short film by the immensely talented Clemens Wirth. Wirth has an interesting niche, he carves scenes of our planet by hand in miniature. It’s a painstaking process where every grain of sand, every rock, every blade of grass is created individually and shot on camera; the attention to detail is second to none. To do this justice, our attention to detail when composing the audiotrack had to be second to none too.

Play Mini Landscapes by Clemens Wirth on Vimeo

The starting point

To complement the film’s hand-crafted, fragile construction, we knew we needed a score that was both powerful and uplifting but also had a delicate, organic feel. This led us to design a sonic palette where many sounds are heard only once and every musical element has a warm, intimate texture.

We started with lush, ethereal pads that would act as the foundation for the audio, bringing to life the slow, evolving shots Wirth had created. Inspired by ambient masters like Eno and Harold Budd, these formed a bed of warm textures that evolve, shift, and collide throughout.

At work on Clemens Wirth’s recent film

To produce these, we took recordings from various synths, pads, and pianos and loaded them into the software Paul Stretch, drastically warping them into ethereal sonic beds. From this, the score and the sound design had a textural starting point from which to develop. As mentioned in our last piece, a strong musical foundation is essential when producing professional audio.

Let sound design be musical

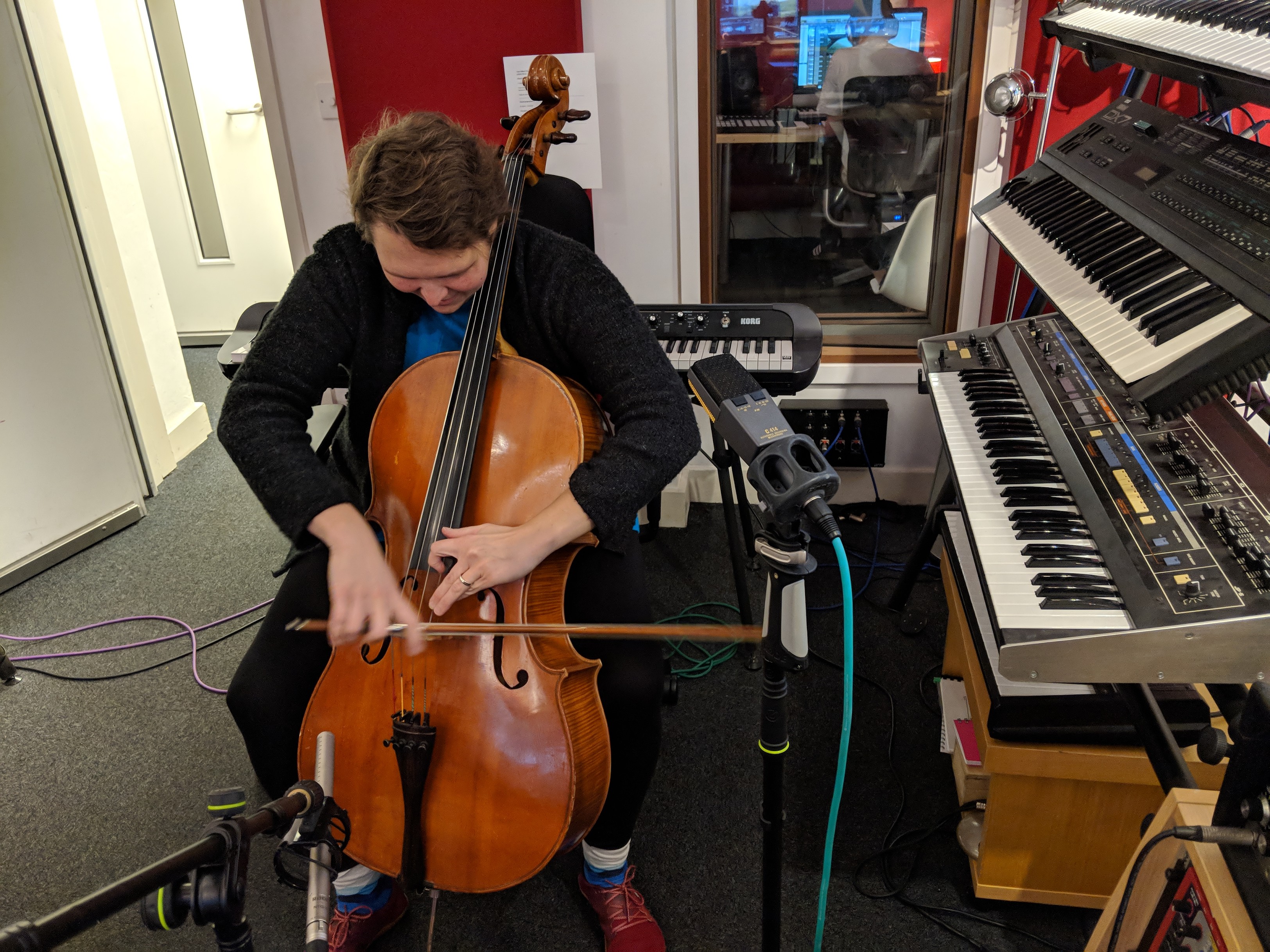

Using this foundation, we introduced sounds that had a musical element but were structured to work as builds, transitions, and effects, complementing the specific scene on screen. We used reversed cello recordings from Lucy Goldbridge, sub-bass and icy pads during the towering glacier shots, and scratchy, tremolo strings during desert scenes. These one-off sounds all helped contribute to the authenticity and intimacy Wirth was striving for.

By playing with these musical textures in a fashion more akin to designing sound effects, the distinction was less obvious, creating a much more immersive, detailed track. This approach is fundamental to immersive audio; being able to find unique ways that the effects and score can dance together without the constraint of fitting into purely ‘FX’ or ‘music’.

Lucy Goldbridge in the studio

To add to the evolving intimacy and warmth of the piece, we recorded the piano part live. Sample libraries and synths can be great for this, but the human element is sometimes lacking. As mentioned in our first piece, imperfections and artifacts are often crucial when creating authentic audio.

As we progress through this short, beautiful journey of our planet, we come across different environments with different weather patterns. The sound design further helped bring these to life, adding bass and texture, developing from the pads underneath and boosting the less pronounced frequencies in the score.

Neutron 3 in Echoic Audio’s sound design workflow

Less is more

Taking the warm, human element even further, we collaborated with a dulcimer player, Joshua Messick. Inspired by the likes of Dead Can Dance, he played an emotive, arpeggiating pattern. We wanted to use it within the main body, but the long, sweeping camera shots were better complemented by evolving pads with the piano over the top, so we didn’t include it here. Sometimes less is more. Yet, it worked really well in the ‘making of’ section at the end, and added extra energy to this final part. You have to experiment to get the best out of the idea—the initial plan isn’t always the end result!

Attention to detail in music and sound design is crucial, especially when producing audio for something as intimate and delicate as abstract short films. This doesn’t mean your audio needs to be complex—less really is often more. What it does mean, though, is that everything should be clearly defined, with a meaningful presence, whilst also enhancing the piece as a whole. Well-organized, detailed sounds often combine to create a cohesive soundtrack that is greater than the sum of its parts.