The Mixer's Guide to Loudness for Broadcast

We define what the CALM ACT means for mixing audio in post-production contexts like commercials, episodic television, and more. Plus, learn how to meet the regulations.

As re-recording mixers, there is nothing like starting a new mix; the feel of faders under your fingers, the warm glow of the computer monitor on your face, and the wonderful prospect of a creative day ahead of you. Then someone spoils the mood by handing you the delivery requirements.

“Wait, what? Why is this different from the last show, the other network, the other streaming service? We were under the impression there were agreed upon guidelines, a paper called ATSC A85 that documents firm loudness recommendations. It’s practices are even mandated in an act of Congress called the Commercial Advertising Loudness Mitigation (CALM Act).”

So how is it every delivery sheet we get asks for different loudness specifications?

This is what the CALM Act says

The Commercial Advertisement Loudness Mitigation (CALM) Act was passed on September 29, 2010. The bill was proposed in the house of representatives by congresswoman Anna Eshoo from California. Legend has it she was inspired to write the bill after disproportionately loud television commercials interrupted a holiday dinner she was hosting.

Conceived as a solution to the loud commercial problem, the CALM act references something called the Advanced Television Systems Committee (ATSC)’s Recommended Practice A/85. The full document is available at atsc.org, but we’ll attempt to convey the highlights.

As ATSC A85 gets updated, the CALM act is automatically updated to reflect any new recommendations, so in essence the CALM act is bound directly to A/85.

From the FCC website:

“Specifically, the CALM Act directs the Commission to establish rules that require TV stations, cable operators, satellite TV providers or other multichannel video program distributors to apply the ATSC A/85 Recommended Practice to commercial advertisements they transmit to Viewers.”

While the scope of this bill is directly focused on commercials, if you mix episodic television, be it long form or half hour, by association you must mix within the guidelines of this act. The intent is that when watching TV, viewers can go from program to commercial and back to program without any apparent change in loudness, and as you change channels you can go from one to the next with the same experience.

It’s worth mentioning that prior to the creation of this legislation, the number one complaint to the FCC with regards to broadcast television was the unpleasant loudness of commercials. Since the time the act took effect on December 13, 2012, it’s worth noting that the number one complaint to the FCC in regards to broadcast television is... still the loudness of commercials. OK, so apparently the passage of the act didn’t work out exactly as planned.

This begs the question: “Why are we adhering to a regulation that affects how we mix and potentially limits our creative choices for a set of rules that seems to be having limited effect on the overall problem of disproportionately loud commercials? And what does this tell us?”

First, it tells us if you want anything to happen in Washington you should start by interrupting a congressperson during their dinner. We also learned that these rules and regulations are not succeeding exactly the way they were meant to. So we decided to dig in and find out why.

What we found out is that the CALM act could, and indeed should very well do what it was designed to do: The problem is that each network and content provider has interpreted A85 in a different way, resulting in differing criteria for delivery that is directly undermining the effectiveness of this regulation.

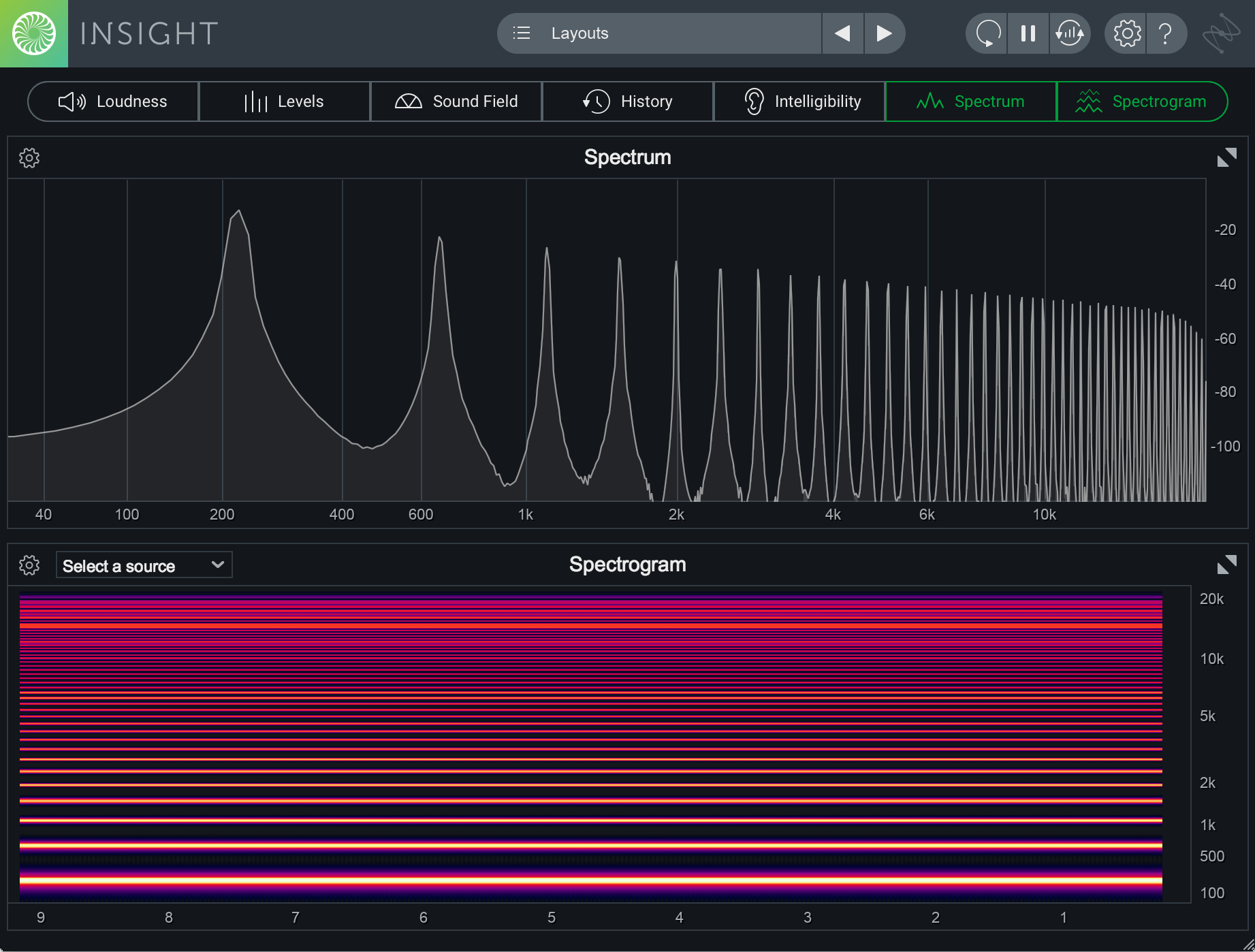

iZotope Insight Measuring Loudness

In practice, this is what happens

Let’s look at the recommendations for commercials (short-form content) vs the TV shows we are mixing and watching (long-form content). The A85 document focuses on commercials in no uncertain terms:

“For short-form content, A/85 recommends that the average loudness of the full mix be measured over the entire length of the item.”

By contrast:

“For long-form content, A/85 recommends identifying and measuring the anchor element during audio mixing and ingest. The anchor element is usually dialog, which the listener would tend to focus on when setting the volume control. The loudness of the anchor element would be reported as the loudness value of the program for a properly mixed program.”

The intended implementation of this spec for programming is to sample a representative portion of the show and measure it to make sure the dialogue is within a specific range of “loudness,” as defined by the BS 1770 LKFS (or LUFS) measurement. It’s not necessary to measure the entire show. It’s not even necessary to measure one representative segment per act, but that would also be a reasonable way to do it.

What it categorically does not require, is the measuring of the entire program, from start to finish, of all content across all channels of the full program mix.

Please read that last sentence again because this is the core of what this discussion is all about.

It’s also not necessary to limit true peak to -6 dBFS, which is what a number of cable content providers have also chosen, but that’s almost another conversation. Lowering true peak to -6 dBFS does further restrict our dynamic range, and can have the effect of making mixes sound louder, harsher, and more squashed. This could also lead to yet another connected issue, that of the inclusion of loudness control devices in the broadcast chain (such as the Evertz Intelligain box) but that is another discussion entirely.

It’s worth noting that people around town colloquially use “dash three” as an interchangeable term for “full program loudness.” This isn’t strictly accurate, since 1770-3 can measure dialogue as the anchor, but the user has to specifically isolate the dialogue in order for this measurement to be taken correctly, whereas in 1770-1, Dolby Media Meter (the most commonly used tool for measuring LKFS) had separate readings for dialogue loudness and full program, or “infinite all” loudness. The reasons for the exclusion of this are technical and have to do with the inclusion of a gate in 1770-2 and -3, and the phrase “don’t gate the gate,” but all of this just goes to further show that we don’t, as a community, fully understand what it is we’re measuring and how.

So, herein lies the breakdown of the process: We are, as mixers, asked to deliver shows to specs based on what appears to be a misunderstanding of the A85 recommendations, and the unintended consequence of this misinterpretation is that a lot of program content is actually made quieter than the commercials, flying in the face of the CALM Act and the intention of A85 to set loudness but maintain dynamic range and quality of mix.

What it looks like

We’ve spoken to some very knowledgeable people about this issue in a lot of detail, and we have it on about as solid authority as you can get that full program mix measurements, when substituted for a dialogue anchor based measurement, will not yield the intended results of A85.

So here is an example of what happens when we run two stylistically different shows through iZotope Insight and look at the LUFS measurements:

First, let’s measure a dialogue driven, single camera comedy show (the CW’s Jane the Virgin), with no big action sequences or music. If we measure the representative dialogue, as per the A85 spec, we will get a figure reliably close to -24 LUFS for any given section of the episode. The overall average of an episode of the show with sections sampled at random is -21.7 LUFS, measured using Dialogue as the anchor (fig.1).

If we then measure the entire episode across the whole mix, we’ll end up with a similar reading of -21.9 LUFS Full Program (fig.2), because the content is consistent and doesn’t have a very wide dynamic range, being a dialogue driven comedy and all.

Figure 1—Loudness Measurements for 'Jane the Virgin,' Isolated Dialogue and Full Program

Figure 2—Loudness Measurements for 'Jane the Virgin,' Isolated Dialogue and Full Program

Going in and out of commercials with this measurement will sound fairly even, because the commercials are measured across their entire length and content, and so the dialogue level of the show will be very close to that of the ads and transitions will be smooth.

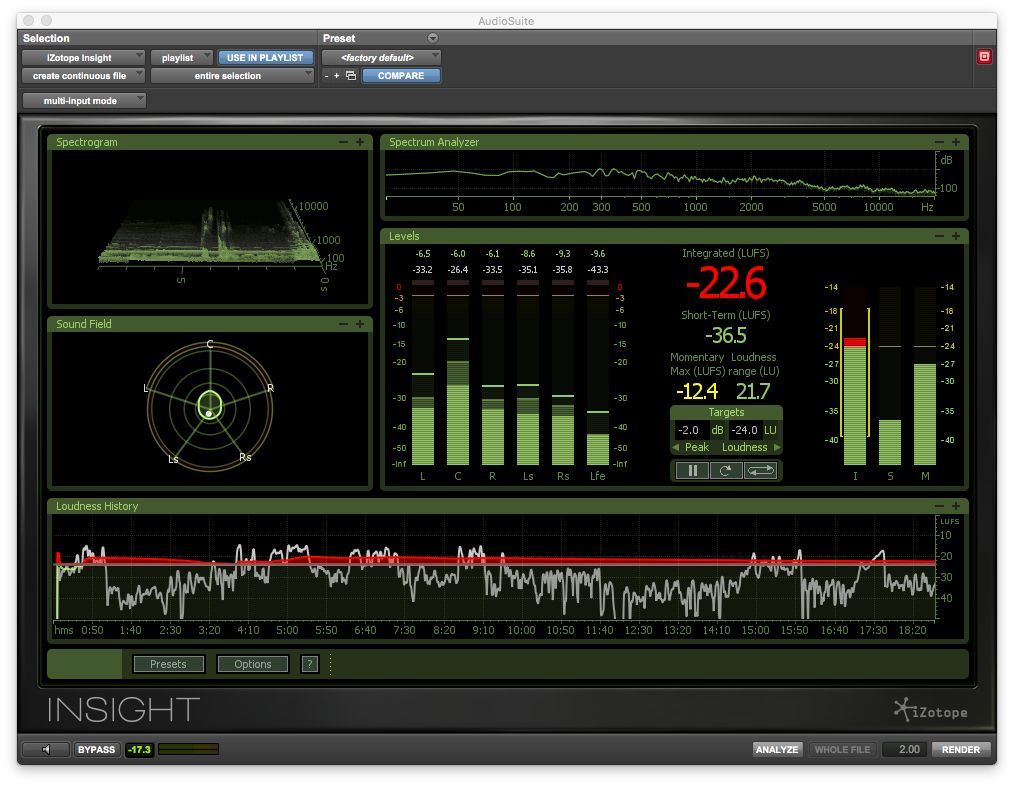

Contrast this, then, with an action packed, dynamic show with explosions and gunfire (National Geographic’s The Long Road Home, a shameless plug for one of our mixes). Episode 7 of that show came in at -22.6 LUFS at 1770-3 (fig.3), when measured full program mix, yielding an isolated dialogue measurement of -28.5LKFS! (Fig.4) So if the dialogue were moved to the correct pocket of -24, the “infinite all” (full program mix) value is actually -18.1, and completely out of spec!

Figure 3—Loudness Measurements for 'The Long Road Home,' Full Program and Isolated Dialogue

Figure 4—Loudness Measurements for 'The Long Road Home,' Full Program and Isolated Dialogue

All of this means that the comparative level of the dialogue between our action packed show vs the comedy and the commercials is much lower, keeping in mind that people will set their volume controls to the storyline’s dialog anchor element, and with good reason. The concept falls apart further when we are asked to deliver -24 LKFS for the whole mix “act by act”—this means that in an instance where an episode starts off with the first couple of acts being dialogue driven and without any action sequences, and then progressing the story into the last couple of acts with intense action, the explosions and gunfire in the crescendo of the story will not seem any louder than the spoken dialogue in the first acts, and then the commercials will come barreling in seemingly twice as loud as the action. Additionally, using an infinite all, full program mix measurement skews the levels between episodes of the same show, so if one were to binge-watch The Long Road Home, they’re going to have to adjust the level between episodes.

As a side note, another development that is bound to affect this issue somewhat is that Dolby is about to cease support for their industry standard loudness tool, Media Meter, which means the industry will be looking to switch to a new standard tool for these measurements. In this case we used iZotope Insight.

Conclusion

To be absolutely clear, long-form programs are supposed to be mixed and measured with a dialog anchor, not a full program measurement. 1770 -1 works well for this because dialog is the focus. 1770-2 and 1770-3 will work, but it’s not necessary to deviate from 1770-1 once dialog is established as the anchor and focus of the measurement. A/85 2013 contains a footnote grandfathering -1 in this application—long-form content is not to be measured full program, or even the entire length of the show, and certainly not act by act.

The end result of this misapplication is that we have content on any given television or cable channel, streaming service provider, or even a box set of DVDs or BluRays that can have an up to 10 dB swing in apparent loudness. So that’s between channels, between services, or even between episodes of the same show on a single service.Given that the stated goal was to unify and normalize the user experience, it seems quite apparent that mistseps have been made.

But it’s not too late—if we can all agree on the best implementation of the standard (and from our discussions here, it truly seems that we can), then we should be able to stop, re-calibrate, listen, and then move forward with a delivery spec across all platforms that allows the shows to be presented in a consistent, dynamic, sonically rewarding fashion that satisfies the creative intent of the filmmakers while simultaneously meeting the legal requirements of the CALM Act and the recommendations laid out in A85.

As crazy as we might be, that doesn’t seem crazy to us, and we encourage the discussion, participation, and engagement of our collective sound community in order to make this a reality.

Please feel free to contact us at King Soundworks with any thoughts on this matter, as we endeavor to arrive at a unified spec. Additionally, we’re striving to put together an event with the ATSC, Dolby, and as many content creators and providers as we can rally in order to discuss the current situation, enlighten stakeholders and strive to achieve the intended outcome as intended.

We can be reached at:

jon@kingsoundworks.com

greg@kingsoundworks.com