What is signal-to-noise ratio? Why it matters for mixing

Learn what signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is as well as how to hear and fix signal-to-noise ratio issues when mixing.

As you embark on the journey of audio production, you will encounter a critical term: the signal-to-noise ratio, often abbreviated as SNR. Often found lurking at the back of gear manuals and plugin documentation, SNR is more than a technicality: it's a pivotal measurement defining the balance between your desired audio signals and their inherent background noise.

This article will explain signal-to-noise ratio, demonstrating its real-world significance in the realm of mixing. Relax, we won’t cloud your head with fuzzy math here. Instead, you’ll learn practical tips for how to understand the signal-to-noise ratio, discover what is a good signal-to-noise-ratio, and how to fix SNR issues when they come your way.

Follow along with

RX 11 Advanced

What is signal-to-noise ratio?

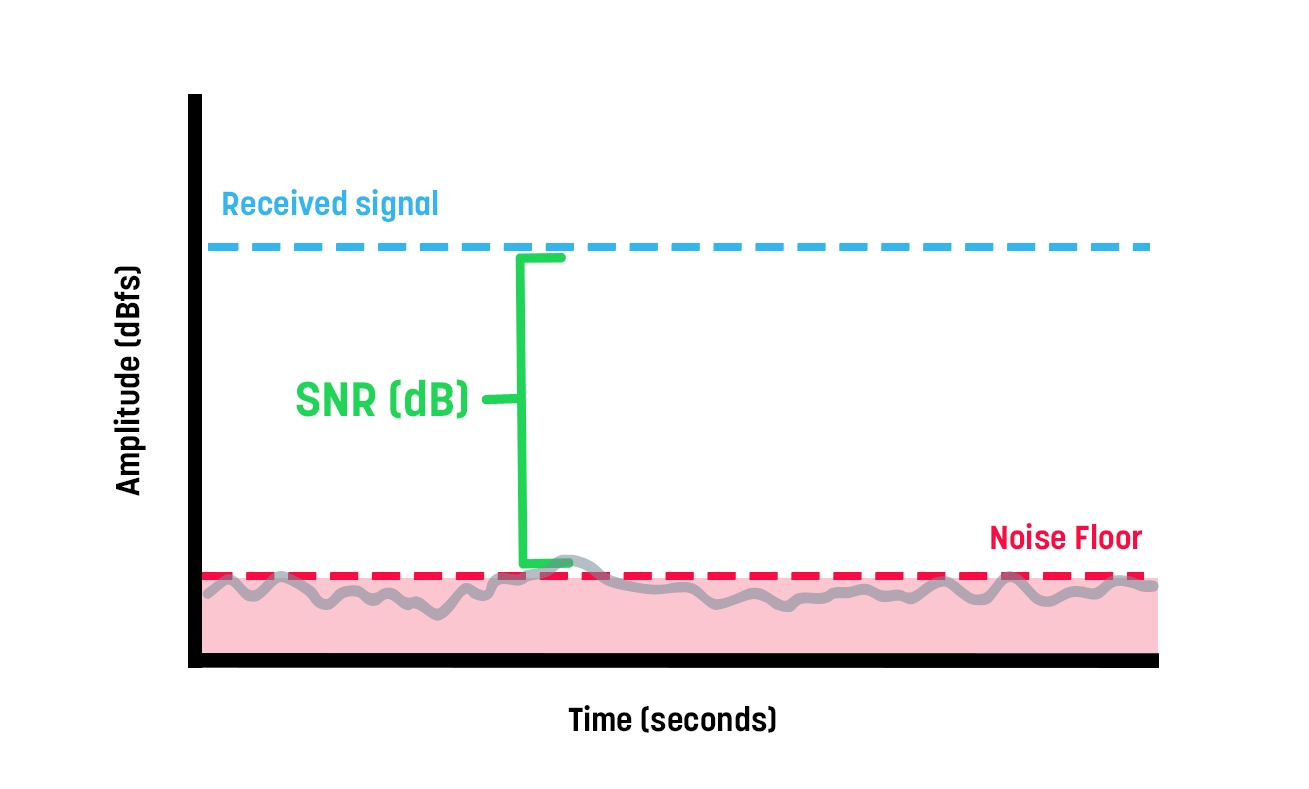

All pieces of analog gear share common characteristics – and a few of them are germane to our purposes here. The first is the noise floor, which doesn’t need much in the way of clarification: any audio signal hovering near the noise floor will be audibly encapsulated by the inherent noise of the hardware’s operation (what we often call its “self noise”).

Another term to grab hold of is “nominal level.” You can think of nominal level as the volume at which a piece of gear is designed to operate (of course, “volume” is a misleading term in its own right, but it’s colloquially understood by most people).

When an audio signal is playing through a piece of analog gear at nominal level, there’s a good amount of wiggle room. You have lots of space to turn it down or up before you hit the noise floor at the quiet end of the spectrum, and all-out distortion at the loud end.

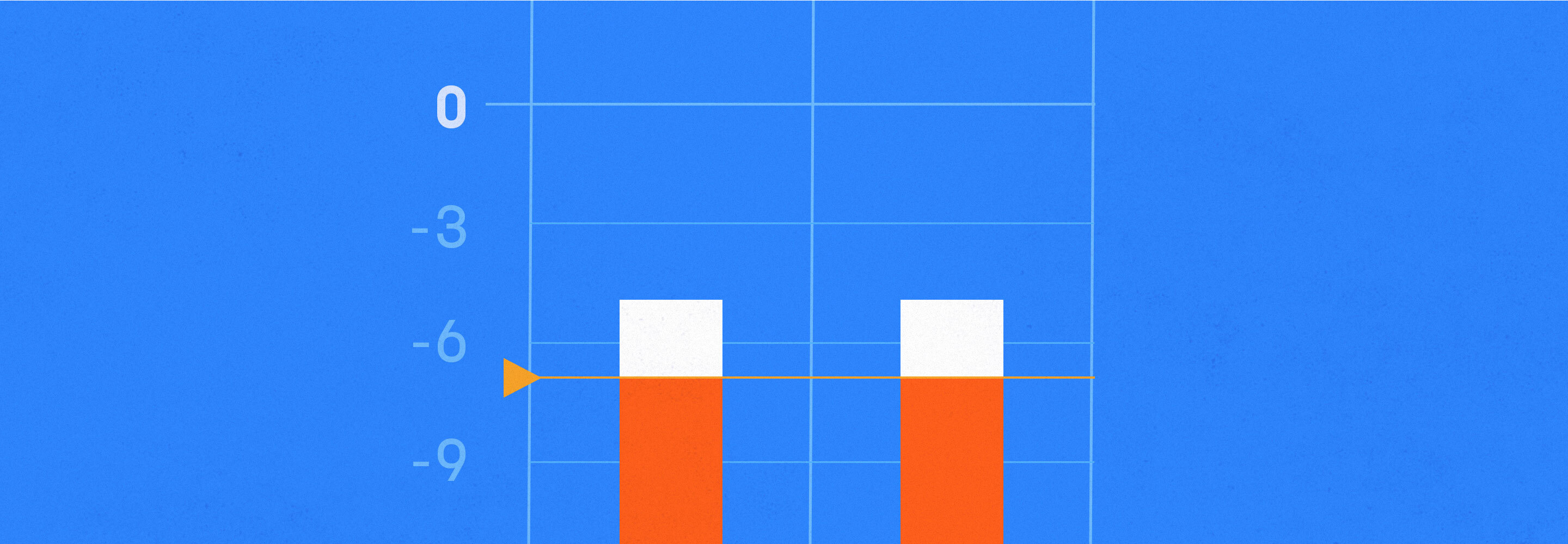

We call the space between a signal’s operating level and its maximum level “headroom” – a concept we’ve covered in other articles. The difference between your nominal level and the floor, on the other hand, is your signal-to-noise ratio.

Signal-to-noise-ratio

That takes care of analog equipment – but what about digital signals?

The answer is a bit complicated, as we get into questions of dithered signals, truncation, and other concepts outside the scope of this article. But you ought to keep this in mind:

We all love analog-modeled plug-ins, right? Sure, a digital compressor is fun to tweak, but who doesn’t like playing with the virtual knobs of an emulation to get a more colorful sound?

Well here’s the thing: plug-ins that model analog gear often emulate the hardware right down to the noise floor, meaning you can inadvertently add noise to your signal by using them. I’ll demonstrate in the following video:

When it comes to SNR and analog emulations, it’s an exponential pipeline. If you take one noisy track, play it alongside another, pipe it through a submix with effects on the bus, and funnel all that into multiple rounds of mix bus and mastering processing, you will be lowering the signal-to-noise ratio a lot.

How do you calculate a signal-to-noise ratio?

Congratulations: if you’re not a math person, you’ve just opened a whole tin of worms with that question. There are a lot of ways to calculate the signal-to-noise ratio of something, all depending on your context. The formulas change whether you’re measuring Watts or Volts, and whether you’re dealing with absolute units or logarithmic ones (such as the dB).

When thinking about how to calculate signal-to-noise ratio, you're always comparing what you would consider a desired audio signal (what we defined as nominal before) to what you’d consider unwanted noise (hiss, hum, crackle) – but the formulas themselves change depending on the circumstances.

Luckily for you, you’re probably not going to be busting out math equations and measurement equipment to check the integrity of your signals. It’s going to circle back to your ears – to hearing a high signal-to-noise ratio, and distinguishing it from a lower one.

In addition, most pieces of analog equipment you’re using already has had their signal-to-noise ratio calculated and listed by the manufacturer.

Why the signal-to-noise ratio matters in mixing

You don’t need to walk around with fancy measurement equipment and a pocket protector to achieve the creative tasks of mixing. No one is saying that here. But you should be cognizant of the signal-to-noise ratio in your mix. Why? Because we, as engineers, use a lot of tricks that bring up the noise, as well as the funk.

Here’s a beautiful guitar part.

Here it is if I raise the level 8 dB.

Whoa – there’s way more noise in there!

Here’s what happens if I try to make it a little brighter with EQ.

That’s even more noise. Now, what if we need to add compression?

That’s a whole lot of noise for just one track. And again, you need to remember that we’re constantly blending disparate tracks into one cohesive whole. When you’re mixing, you’re not only summing the beautiful tones of all your tracks together – you’re also amplifying the background noise.

Do I want a higher or lower SNR?

If you’re trying to get the platonic ideal of a perfect sound, you want a higher signal-to-noise ratio. A higher SNR represents a stronger musical signal compared to the noise-floor – a purer sound with less getting in the way between the music and the reproduction thereof.

If you’re perusing those tech specs on that new interface or and you see an SNR of 40 dB or higher, that’s golden – if you want a clean sound.

But as in all things, music is far more complicated than the platonic ideal. Famous bands like the White Stripes and the Black Keys practically built their whole careers on lower signal-to-noise ratios. And no, that’s not hyperbole: that “down and dirty” “authentic” and “lo-fi” sound attributed to those bands is situated not only in their grooves, but in the noisiness of the recordings themselves.

All things come down to taste. If it fits, it fits. Here’s a real-world example:

Recently, I was mastering a song for Olivia and the Lovers, a Chicago-based Queer Country band. The mix sounded good, but brought from its healthy mixing level to a commercial target, the signal-to-noise ratio was lower than they might want, due to the real-world amps used and the processors employed in the mix.

In this case, however, the band wanted the noise, because it fit with the aesthetics of the song.

How to fix an SNR issue in the mix

Maybe you’re given noisy tracks and the imperative to get a higher signal-to-noise ratio. How do you go about fixing a noisy track?

You have a couple different options. The first is a carefully tuned EQ curve involving a high-cut or high-shelf filter to take the hiss out of the high-end. For instance, here’s a guitar part with EQ used to filter out some high-end amp hiss:

EQ for taking out amp hiss out of electric guitar

However, this approach can be too broad – especially for content that needs its high end preserved. In these cases, RX comes to the rescue with its Spectral De-noise module, and here’s a video showing how.

Here are some basic steps to fix SNR issues:

- Open your audio in iZotope RX and select the Spectral De-noise module

- Make a selection of the longest section of noise you can find in your audio (ideally a few seconds long)

- Click the Learn button to capture a noise profile

- Once the noise profile is learned, adjust the Threshold and Reduction settings to reduce the noise to taste.

- Select the Bypass button to hear the audio before and after the noise is reduced

- Press Render when you are ready to commit the changes

It's best to do this at the beginning of a song. The most likely time SNR issues are going to occur are the softer parts of the song, when noise issues are most audible.

All funk, no noise

Navigating the intricacies of the signal-to-noise ratio is an essential aspect of achieving sonic excellence in your mixes. Whether aiming for pristine clarity or embracing the raw authenticity of a lo-fi aesthetic, understanding SNR empowers you to make intentional choices that align with your creative vision.

As demonstrated, real-world scenarios often dictate the balance between signal purity and background noise. Remember, the ultimate goal is to serve the music.