Headroom: How to Set Your Levels in Mixing and Mastering

Learn what headroom is, why it's important in both mixing and mastering, and how it ties in to the related concept of crest factor.

The concept of headroom is one of those foundational elements of any audio engineering discipline that gets glossed over all too often. If the term “headroom” is new to you, welcome. I’m glad you’ve found your way here first! If you’ve heard a few different explanations and are feeling rather confused, wondering why people keep telling you things like, “leave 6 dB of headroom for mastering,” welcome to you as well. We’re going to get this all sorted out.

If you feel like you’re a headroom pro, I’ll encourage you to stick around, too. You may see things from a new perspective, or find useful ways of explaining headroom to your less experienced friends and colleagues.

In this piece you'll learn:

- What headroom is and how it relates to crest factor

- How to utilize headroom during mixing

- The role of headroom in mastering

Follow along in your DAW

Experiment with headroom in mixing and mastering by using

Insight Pro

RX 10 Standard

iZotope Music Production Suite Pro: Monthly

What is headroom?

Headroom is defined as the available level above the nominal level before clipping. In order to fully understand this definition, we need to make sure we have two other terms under our belt as well: clipping and nominal level.

Clipping is essentially the level at which an audio system runs out of steam. If you try to increase the level of your audio past this point, rather than an increase in output level you simply end up with distortion. In a fixed point digital audio system this is 0 dBFS—decibels full scale. In professional analog equipment this is often about +24 dBu—although I’ve seen hardware with clipping points anywhere between +18 and +28 dBu.

Nominal level is perhaps a bit more esoteric, especially if you’re accustomed to dealing with digital audio. In analog audio equipment, however, the nominal level is defined as the average signal level at which the device is designed to operate. For professional devices this is almost always +4 dBu. In a purely digital environment this concept doesn’t make much sense, but if we think about an audio interface—where digital meets analog and vice versa—we can start to bring some definition to it. Most professional audio interfaces are designed such that +4 dBu on the analog side ends up being somewhere between -20 and -14 dBFS on the digital side.

And this brings us to our headroom definition: Headroom is simply defined as the available level above the nominal level before clipping. That’s it! So, for example, if a system has a nominal level of -20 dBFS—or +4 dBu—and a clipping point of 0 dBFS—or +24 dBu—it can be said to have 20 dB of headroom since the clipping point is 20 dB above the nominal level.

Next, we’ll look at how the concept of headroom fits into mixing and mastering, how it relates to crest factor—which is not the same as headroom—and what some of the common language around headroom really means.

Bonus: Learn more about the impact of audio technology from experts across the audio and music worlds on the Headroom podcast series with iZotope Education Director, Jonathan Wyner.

Headroom and levels in mixing

While the definition of headroom is fairly straightforward, it may not be readily apparent how it connects with phrases like, “make sure to leave some headroom.” What something like this ultimately means is, “don’t use all of the available headroom of the system,” or “make sure your highest peaks aren’t right up at the clipping point.” But why is this important, and what’s the best way to do this practically during a mix?

Let’s start by looking at why leaving some headroom is important during mixing. First of all, if you’re working on a mix and setting things up so that your peak levels are very near the clipping point—0 dBFS—early on, you can paint yourself into a corner fairly easily. Whether you want to make some level tweaks, or find that a certain section of the song just naturally gets a bit louder, you can easily get into unwanted distortion territory. Fixing this may be as easy as pulling down the master fader, or all the individual faders, but if you’ve already gotten into level automation or bus compression this can quickly turn into a pain. Better to set your levels from the outset so that you can make use of the ample headroom.

My favorite way to do this is by using the K-System metering approach, specifically, the K-20 setting. You can set

Insight Pro

Once this is set up, I like to start adjusting rough levels for a mix by setting the bass, and kick drum so that their average levels—the brighter, slower moving part of the meter—are a few dB below the 0 mark, where the meter transitions from green to yellow. From there, I forget about the numbers and use my ears to adjust everything to taste. If you build a well balanced mix, you’ll likely find that at the loudest points in the mix the average levels get up to maybe the +4 or +5 mark on the K-20 meter, just poking into the red, but that your peak levels are still well below the +20 mark—or 0 dBFS clipping point.

Using K-20 metering in Insight Pro

Once you start effectively utilizing headroom during mixing it frees you to play around with the crest factor of your mix without having to worry about clipping. As a quick reminder, crest factor is just the difference in decibels between the average and peak levels of a signal.

Thus, if your average levels stay around that 0 mark on the K-20 meter, your peak levels might be anywhere between +10 and +15 and that would all be perfectly fine, because you’d still have at least 5 dB of headroom. Further, if your peak levels are much higher than that, it may be a good indication that you should reexamine your mix balances.

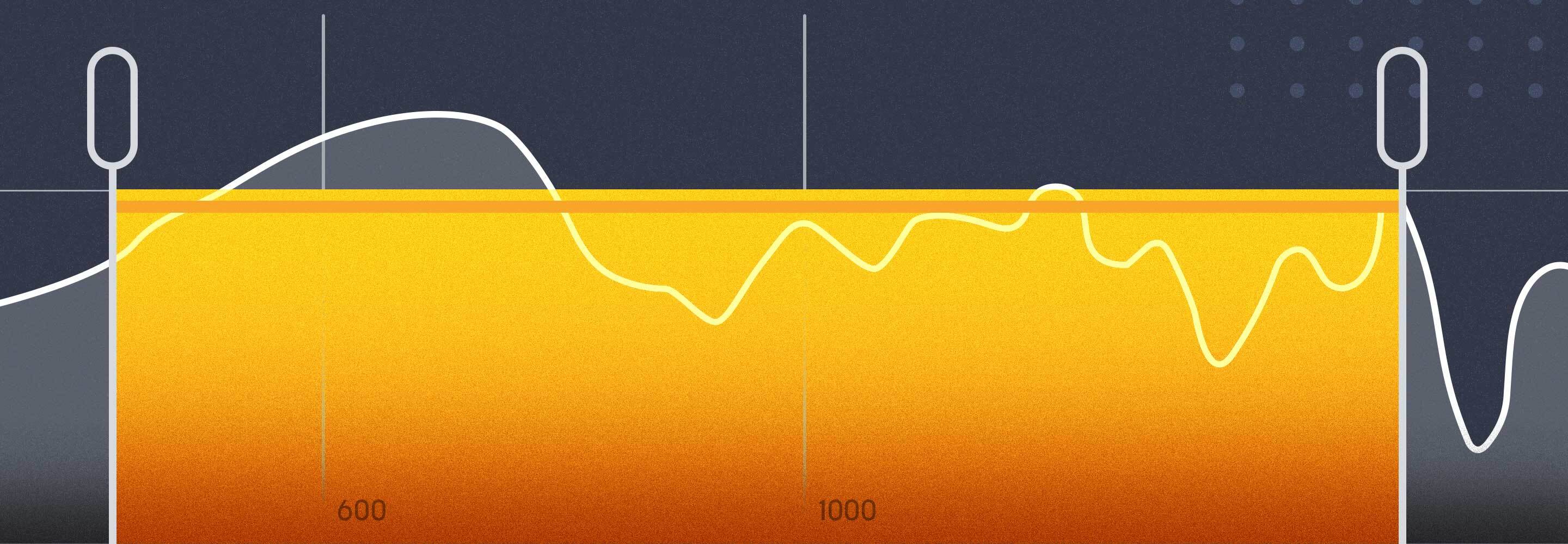

For example, here are two versions of a mix of Dubfire’s “Swerve,” which utilize the available headroom in different ways. First, a version with a crest factor of about 12 dB.

The drums are relatively forward and snappy in the mix, while the bass takes a bit of a backseat. By way of contrast, the second version has a crest factor of about 10 dB. The drums sit back in the mix more, with a bit more sustain and less attack on the kick in particular, and the bass has come forward to drive the mix in a different way.

These are both perfectly valid, conveying the energy of the track in different ways, and in neither case was there any concern of clipping, as you can see below.

Thus, effectively using the headroom of a system ultimately gives you more creative options in your mixing toolbox!

Headroom and levels in mastering

Before we wrap things up, let’s talk a little bit about the role of headroom in mastering. Perhaps the first thing to say is that as long as a mix is not clipped or overly compressed and limited purely for the sake of loudness, it’s completely reasonable to adjust the gain of the mix to create any additional headroom you might need. But why would you need extra headroom? And once you’re done mastering, should you be leaving any headroom?

First, any processing that’s done in mastering is very likely to change the peak levels, and not always in the ways you might think. For example, high-pass filters are notorious for increasing peak levels due to their phase shift, but just about any EQ move has the potential to increase peak levels. Compression, too, could cause increased peak levels if it’s used to enhance transients and make-up gain is used. Since we don’t want anything to be clipped prematurely, it pays to have a little headroom left when we start mastering.

What about when we’re done mastering though? Here the answer is a definitive, “it depends.” To be certain, through the use of gain and limiting we will typically reduce the headroom to under 1–2 dB, but exactly how far we take that will be informed by a few factors. First, if we anticipate that the master will be used anywhere a lossy codec—like MP3, AAC, Ogg Vorbis, etc.—will be involved, it’s a good idea to set your limiter ceiling to leave about 1 dB of headroom.

That said, more and more streaming services are offering lossless and even hi-res streams. If you plan to avoid lossy streams, or simply view any clipping that occurs as a result of lossy encoding as acceptable collateral damage, then it’s perfectly alright to push your ceiling up and leave just 0.3 dB of headroom or so. If you have True Peak limiting engaged in

Ozone Advanced

However, please note that none of this implies anything about average levels, or loudness in mastering. For that, I’ll refer you to this excellent Are You Listening episode.

Start utilizing headroom in mixing and mastering

To recap, the concept of headroom is truly foundational in any audio engineering discipline. In the simplest terms, it points to the difference, in decibels, between the nominal level and the clipping point of an audio system. This helps inform us of how much room we have to play with above the average level of our mix for things like transient peaks and loud passages. It also helps us to properly set up mix levels while leaving room for creative freedom during the mixing process.

However, headroom is not the same thing as crest factor, although the two are related. In fact, if your average level is equal to the nominal level of the system, crest factor describes how much of your headroom you’ve used, and thus implies how much is left. They are distinct terms though, and should not be used interchangeably.

I hope this has helped clear up just what headroom is, what it’s not, and why it’s important to be cognizant of during both mixing and mastering. If these concepts are new to you, I believe you’ll find them useful and empowering, and if it’s old hat, I commend you for sticking around to the end. Hopefully you still got something good out of it. Good luck, and happy headroom excursions!