How the Sound Designers of It Created Fear with Sound

The sound designers from It spoke with iZotope about how they built a sense of fear through the creative use of sound.

Image source: It official website

Paul Hackner is an award-winning sound designer and mixer, originally from South Africa, whose feature projects include the Drive, Sinister, and The Revenant. Kris Fenske hails from Manitoba and has worked on films including The Hunger Games, and Django Unchained. Hackner and Fenske shared some revealing insight on how they creatively used sound to build a sense of fear and support the conceptual structure of the film.

"In the horror genre, sounds do not have to be anchored in the documented reality…Pennywise became part of the wind and fire and echoes featured in the nightmares of each child.” —Paul Hackner

Let’s talk about the vocal processing with regard to Pennywise. I assume the extreme highs and lows started with Bill Skarsgård’s performance, but did you make a conscious effort to emphasize it in the mix? It definitely serves as a sort of metaphor for him being simultaneously evil and playful. And it’s also just really creepy and gross. The lows in his vocal timbre morph into monstrous growls. What other processing led to that final vocal sound?

Paul Hackner: The challenge of the villain in It always boiled down to the question: How do you make a clown scary? Andy Muschietti put everybody on task to unearth the ancient artifacts that made it become Pennywise. For the introduction to Pennywise in the sewer with Georgie, the clown had to be playful and alluring, yet slowly reveal his maniacal and monstrous side.

Throughout the editing period we experimented with bells, popcorn popping, and children's voices embedded in his lines. For his screams and charges, at first all we had were on-set recordings.

The sound of Pennywise’s voice truly began with the actor's performance. Bill Skarsgård experimented with modulating Pennywise’s voice—morphing childlike wonder with animalistic terror. He is one of the most fascinating voice actors I have worked with. As he stepped up to mic on the ADR stage, Skarsgård actually dropped his lip, and his face became Pennywise. On mic he explored the full frequency range of his throat and voice including Tuvan-like throat tones.

Our director had a very clear idea of an aggressive and rich sound for Pennywise rushing towards camera. Often Andy would perform his own versions, which were amazing, by the way, and then like in a rock band, Skarsgård would riff off of that.

In the end, the clown’s screams were multiple takes of Skarsgård’s recordings melded with various scary design elements. With the help of RX, we even used elements of the original on-set recordings which had the magic of the original performance.

Kris Fenske: Pennywise’s vocals were one of my initial tasks—coming up with various ideas to present to the director. I tried to think of the act of screaming as something brash, offensive, certainly high in frequency and volume. So there was just a multitude of various things tried out. From animal sounds like horses and crows, to very synthesized electronic sounds, and using actual screams.

I think the strangest approach was trying to really fit into the idea of “a clown” and actually experimenting with horns and other circus sounds. That might have been too much on the clown nose, but it was fun to try.

You make creative use of score, sounds, and songs as three sort of buckets that each scene falls into. For the first half of the film, each one almost exclusively has its own role: the “score scenes” are emotional/dramatic, the “sound scenes” are scary/intense, and the “song scenes” all involve some kind of childhood/loss of innocence (bullying, growing up, etc.) This sets the foundation nicely for the second half of the film which operates in a more conventionally-scored manner. Was this a conscious decision or something that happens naturally?

PH: The very essence of It was a coming-of-age story. Emotional scenes were driven by the majestic score from Benjamin Wallfisch as well as the cues discovered by music supervisor Dana Sano and her team. There were ebbs and flows that called for sound design elements. The kids of Derry live in this ‘80s small-town landscape strangely absent of adults. We had to ask ourselves, “what does summer sound like?”

I became enamored with recordings of distant children playing in real world environments. I extracted fragments of voices and laughs from every recording I could get my hands on. This could only be achieved with the help of iZotope tools that allowed me to extract the fundamental sounds from noisy recordings. There were other small-town summer break motifs, such as trains, insects, dogs, and wind that needed to be isolated (and often mangled) to create a hyper-real environment.

The most emotional ensemble scenes were almost completely driven by music. Growing up in the 80s, my friends and I put enormous attention into making mix tapes. Whether it was the amazing scene of the kids swimming in the quarry or mopping up Beverly's bathroom, the pop music cues playing at full volume transported you into the filmmaker’s mixtape for the Loser’s Club and Derry.

One of my favorite moments is when Beverly arrives at the quarry and she is revealed in slow motion. Victor Ennis, our supervising sound editor, had the simple but brilliant suggestion to put a bird very present in the mix. It had the effect of the birds singing for a princess in a classic Disney film.

As for the second half of the movie, the members of the Loser’s Club slowly become superheroes in their own lives. Sound design had to shift focus to create scale and heaviness and emphasize the mythological power of It and the heroic realizations of the kids. Every time we saw Pennywise or the other incarnations of It, we needed to believe he was big and scary. That meant changing the pitch and depth of his voice as well as creating power and energy in his movements. In order to fight Pennywise, the kids had to wield weapons that seemed deadly and sharp to the monster.

KF: I think any good director and sound team tries to create a film that is constantly interesting. Music and sound design can be competitors, or friends. When they work together and move back and forth at different levels of importance, I think it creates the best type of soundtrack. I think the horror genre really benefits from dynamics. Understanding when to have restraint, and knowing when to go big.

There are several uses of repetition in sound to create tension (e.g., the pages turning in the library, the dripping faucet, the measuring tape being pushed down the bathroom drain, the projector slides turning, etc.). Why do repeated, rhythmic sounds create tension in horror movies? How do you emphasize that with sound design/editing?

KF: It’s not necessarily rhythm itself, but how the pitch, tempo, or volume might be subtly increasing. It’s subliminal tension that the audience might not even realize. It’s a standard sound trick, but really effective.

PH: The real horror of Derry is the complacency of the adults during the horrific events the children endure. Bullying, abuse, and family trauma go unnoticed. The horror genre throws away the rules about what is music and what is sound design.

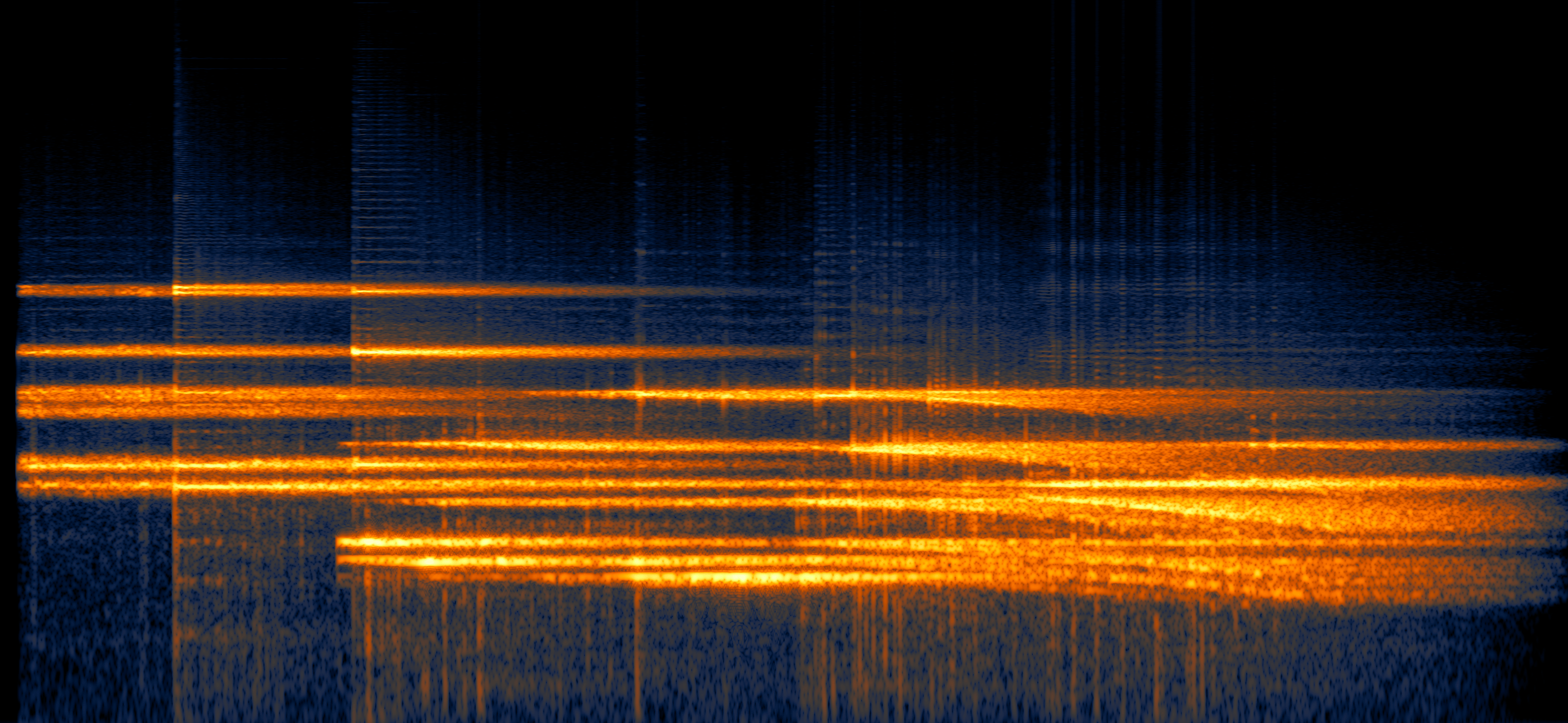

Horror is basically expressed using the soundscape pioneered by Musique Concrete in the early 20th Century. Composers created noise and performed with magnetic tape to manipulate sound recordings—reversing and pitch shifting. In the horror genre, sounds do not have to be anchored in the documented reality. The filmmaker can use a composition of fragmented noises to pierce the character’s sense of memory, fear and pain. It’s fun because it always becomes a magical interplay between the sound effects and score.

Image source: It official website

There were a couple clever moments in It where you use instruments to blur the line between fantasy and reality: the piano in the opening scene is actually the mother playing in the house. And when the flute-holding woman in the painting comes to life, we hear flutes—any other examples of using sound to trick the viewer into being unsure of what’s real?

PH: The monster, It, has a way to permeate Derry like a bacteria. It actually lives in the bowels of the town. Televisions lull the adults into a trance-like submission. Pennywise’s blurred reality was present in every instance of TV audio. He also became part of the wind and fire and echoes featured in the nightmares of each Loser.

Since these uses of sound and music are so effective, it serves to make the silent moments all the more effective. How do you determine which scenes “deserve” total silence? Technically speaking, how are you able to control dynamics to make them work this way?

PH: Andy was very clear about every aspect of the soundscape, especially when it came to dynamics. During the final mix there were many moments when Andy essentially conducted the peaks and valleys of the sound design and score. It was in these moments when perceived silence, created by small transients such as water drips, foot creaks, or actual silence, were revealed, resulting in a dynamic mix. Sometimes it was pure gut instinct like charming a snake.

KF: I think the director is really the one who ultimately decides how any scene is played. We’re just sonically there to support that vision. Of course, having a lot of horror movie experience, I’m always happy to suggest what I think might be something interesting that makes the film hopefully scarier. I’m a really big fan of ambiences and creating an odd sense of environment before something happens. There’s something about backgrounds which seems to be less suggestive, and can really make you feel something without maybe even understanding it.

Image source: It official website

Any remaining thoughts on how the creative use of sound and music in It contributed to scaring the hell out of everybody?

PH: I think from the top down, the horror of Derry was discovered by Andy Muschietti’s team. Supervising Sound Editor Victor Ennis dispatched myself along with sound editors Bernard Weiser, Kris Fenske and Jamie Hardt on various missions to bring terror alive. We continued trying new ideas until something worked.

The best example of this collaboration was the scene with Beverly in the bloody bathroom. That scene was an evolution of design explorations by all of us with the human voice, subterranean sounds, pipe stress, liquid, and explosions. Once I stitched together all of these ideas, our re-recording mixers Chris Jenkins and Michael Keller reimagined the sound design using the immersive capabilities of 7.1 surround as well as Atmos and IMAX. The scene started out as a surround sound funhouse and evolved into bloody disgusting terror.

KF: Hopefully it was accomplished! I take my horror seriously, so I really try to put my best foot forward when it comes to this genre. I love recording new elements, the editing is really fun. I know colleagues who really get squeamish and have absolutely no desire to work in horror. I’ve been privileged to work with so many of my horror movie heroes over the years and I have to say, they’re some of the nicest people I’ve ever worked with. Who would’ve thunk?

Anyway…Happy Halloween!