A guide to fundamental frequency and harmonics in music

Understanding the relationship between fundamental and harmonic frequencies is crucial in audio engineering. Learn their definitions and relationships within.

If you’ve ever heard someone talking about harmonics in music or audio, or perhaps heard them allude to “the fundamental,” and been left scratching your head, this article’s for you. Understanding not only fundamental frequencies and the harmonic series but also how they relate to each other is a key part of becoming a well-rounded audio engineer.

It’s knowledge that will help you understand everything from making better EQ decisions and figuring out why your bass isn’t translating on smaller speakers, to avoiding frequency masking and getting a clearer high-end without harshness. If those sound like things you’re interested in, let’s dive in and discover more about fundamental frequencies, harmonics, and their interrelationship.

Follow along with

RX 11 Advanced

What are fundamental frequencies?

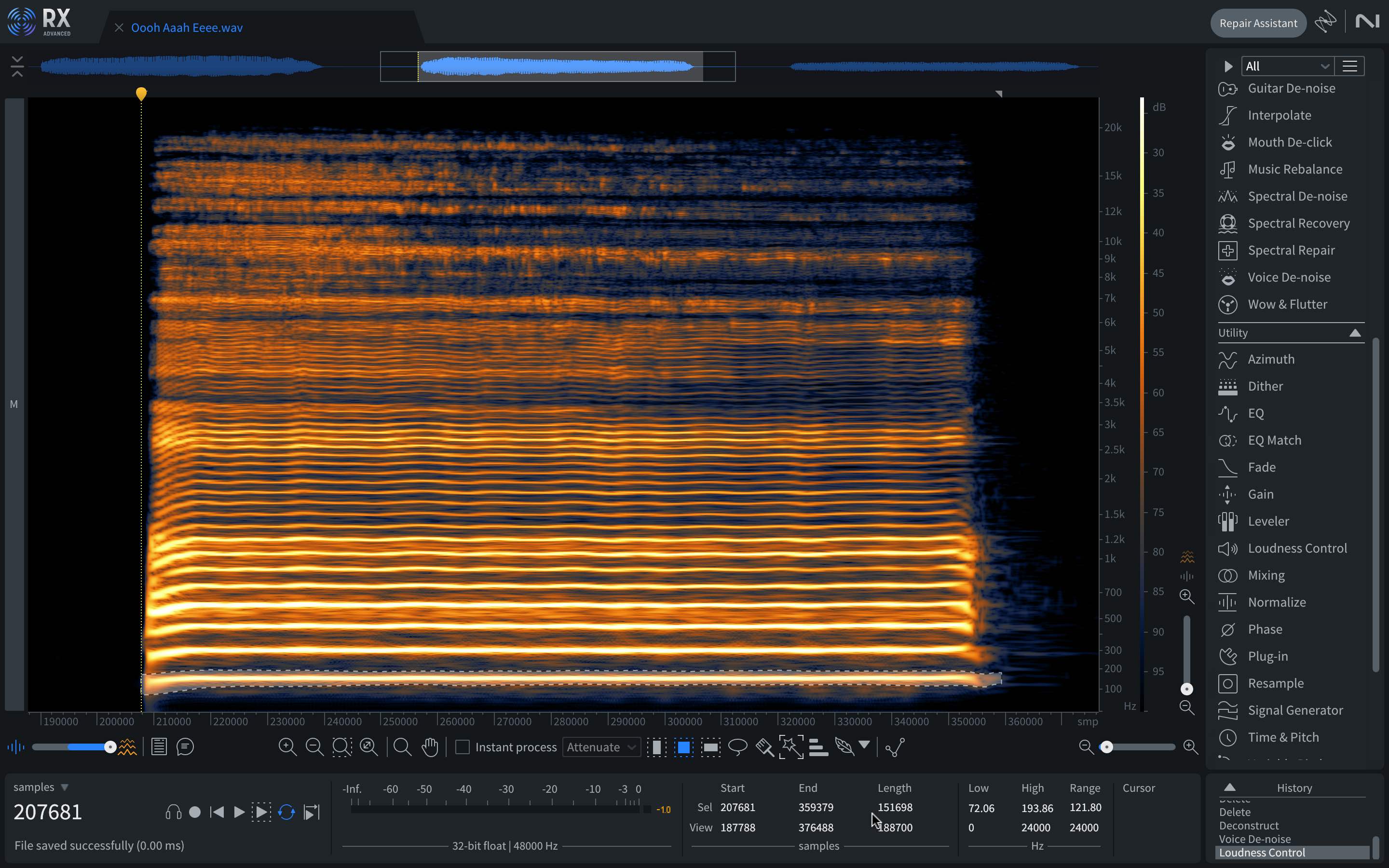

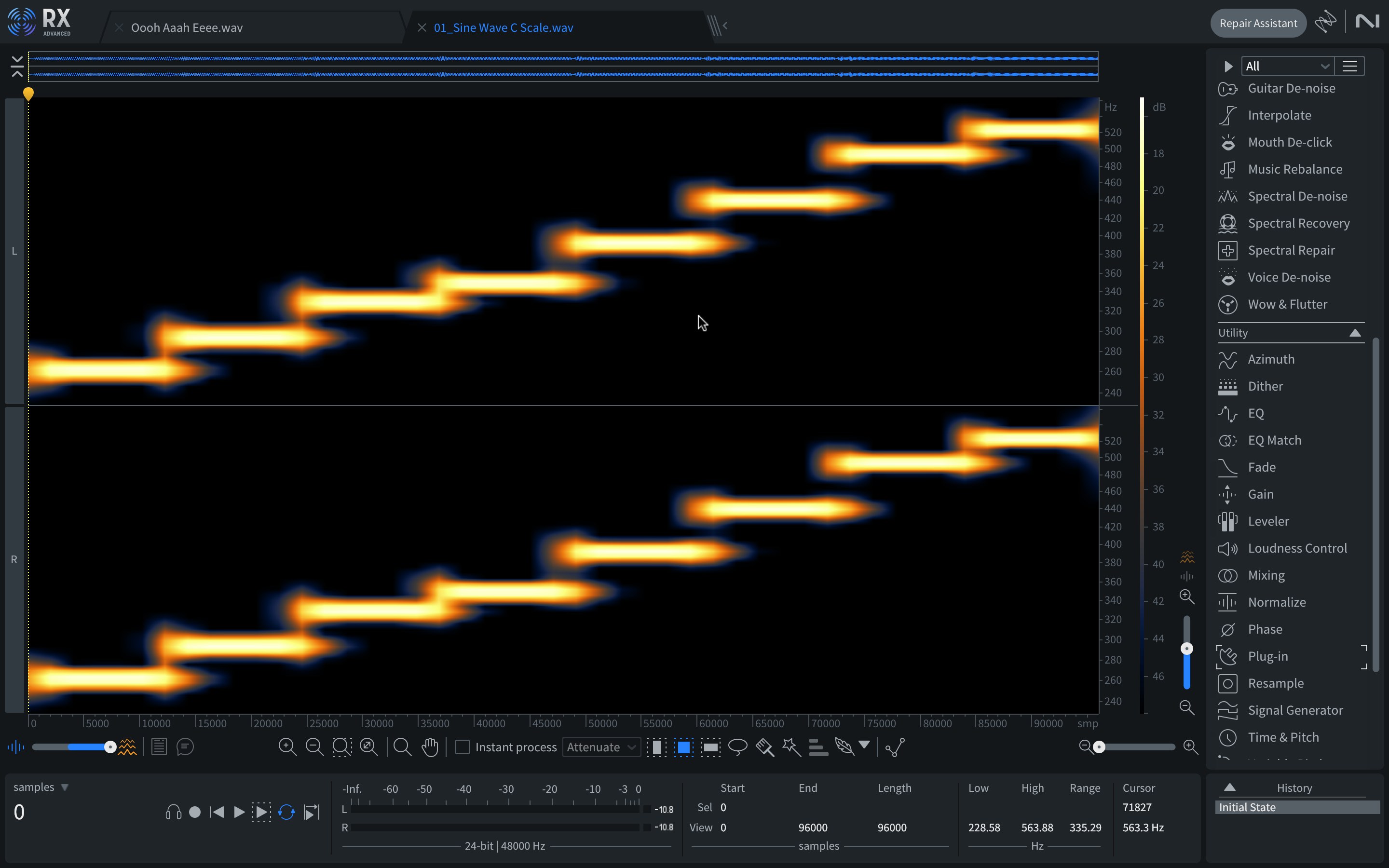

In simple terms, whenever we hear a musical note – whether sung, played by a guitar, trumpet, keyboard, bass, or any other tonal instrument – the pitch that we perceive that note to be is defined by its fundamental frequency. If we were to look at that note in something like RX or the Spectrum Meter panel in

Insight 2

Illustrating the fundamental frequency

Role in defining the pitch of a musical note

The fundamental frequency of a note goes a long way toward defining its musical pitch. For example, if we used the simplest synthesizer we can imagine – one that only plays a single sine wave for each note – we could play a scale and each note would only contain the fundamental frequency for that pitch. That would sound, and look, like this:

A major scale comprised of only fundamentals and no harmonics

When we talk about tuning to A440 – or any other tuning standard – we mean that we’re tuning the fundamental of an A above middle C to 440 Hz. As we’ll see though, harmonics contribute to defining musical pitch as well. In fact, there exists an auditory illusion known as the missing, or phantom, fundamental. More on that below as we cover harmonics.

What are harmonics in music?

Harmonics, or harmonic frequencies, are tonal components of a sound that are higher in pitch than the fundamental. In fact, they have a simple mathematical relationship to the fundamental and are what give different instruments – and even words – their characteristic sounds. For example, the following two sounds use the same fundamentals, and even the same harmonics, but the relative strength of different harmonics gives each a distinctive timbre, or tonality.

Different sounds using the same

fundamentals and harmonics

How harmonics contribute to the timbre and richness of sound

So, it’s not just the presence of harmonic frequencies, but also their strength, or balance, relative to one another and the fundamental that gives each sound its unique tone. Another example. Here’s me singing “Oooh, aaah, eeee.” First with all the natural harmonics in my voice, and then with just the fundamental isolated.

Natural harmonics vs. isolated fundamental

Note how without the harmonics, they all sound very nearly the same! Here’s an interesting thing though. If we remove the fundamental, we still perceive the pitch as being the same.

Natural harmonics vs. no fundamental

Certainly, the timbre has changed and doesn’t feel as rich without the fundamental, but we wouldn’t confuse that for me singing those same vowel sounds – called monopthongs – an octave higher. Some individuals may even still feel that they hear a “phantom” fundamental! In a way, it’s almost as if the harmonics form a map for our ears and brain that points the way directly to the fundamental.

How are harmonics related to fundamental frequency?

Sometimes, you may also hear harmonics referred to as partials, or overtones. These are fundamentally – pun fully intended – three identical concepts. Earlier, I mentioned a simple mathematical relationship between the fundamental and harmonics, so let’s examine that.

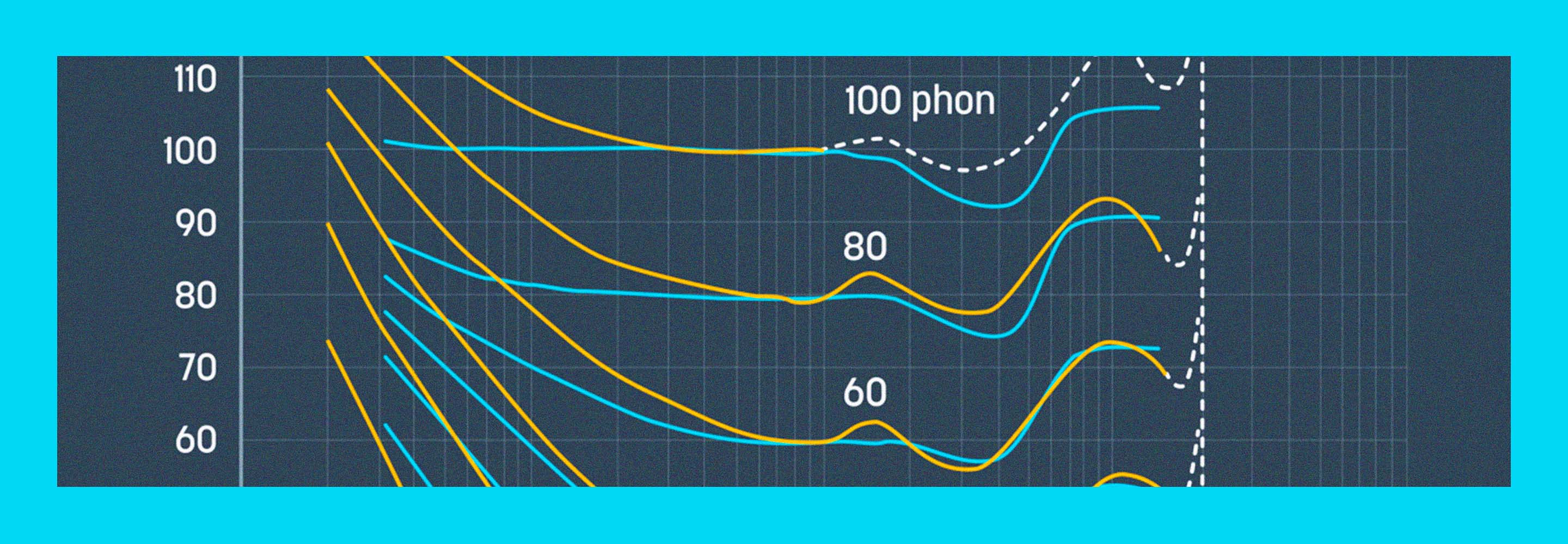

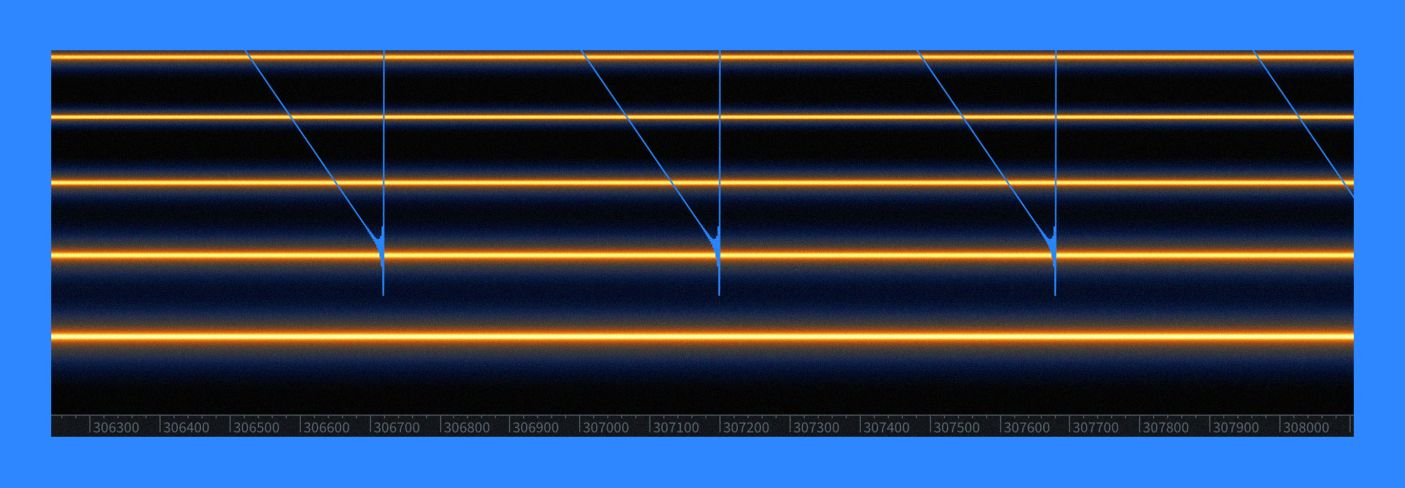

To keep the numbers simple, let’s start by imagining a fundamental at 100 Hz. The harmonics then occur at integer multiples of the fundamental frequency, so 2 x 100 Hz = 200 Hz, 3 x 100 Hz = 300 Hz, 4 x 100 Hz = 400 Hz, and so on at 500, 600, 700 Hz, ad infinitum. We can easily see this if we examine a sawtooth wave, which has the unique property of containing all harmonics.

A saw wave with the fundamental at 100 Hz and harmonics at integer multiples

We can refine this idea a little further to the concept of even and odd harmonics. Even harmonics consist of frequencies at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, etc. times the fundamental frequency, while odd harmonics consist of frequencies at 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, etc. times the fundamental frequency. This can often become relevant when discussing analog hardware – or digital models thereof – as different types of devices will tend to accentuate even, odd, or specific harmonics differently.

What is the relationship between first harmonic and fundamental frequency?

This leads us to a good question though: what about the first harmonic? Does it even exist, and if so what is it? Indeed it does exist. While it’s not often referred to in this way, the first harmonic simply is the fundamental. When we think of it in terms of our mathematical definition, this makes sense: the first harmonic would be 1 x the fundamental, thus it is the fundamental.

The importance of fundamental frequencies and harmonics in mixing and mastering

So, why does any of this matter if you‘re a mixing or mastering engineer? Well, first and foremost, it can help inform our EQ decisions. In mixing, by understanding what the range of the fundamental frequencies is for a given instrument, along with if and by how much it overlaps with harmonics, we can make better decisions about where to boost or cut.

On the other hand, in mastering, the fundamentals of one instrument – perhaps a keyboard – almost certainly overlap the harmonics of another – such as the bass. Understanding which is which, and how they contribute to the tonality of each instrument, can help us determine how much EQ to apply and how to listen for the changes.

Another place it applies in mixing is when considering frequency masking. Depending on relative levels, panning, and other factors, you may find that the fundamental of one instrument masks important harmonics of another, or vice versa. There are multiple ways to address this, but the Unmask module in Neutron makes for a particularly easy and intelligent solution.

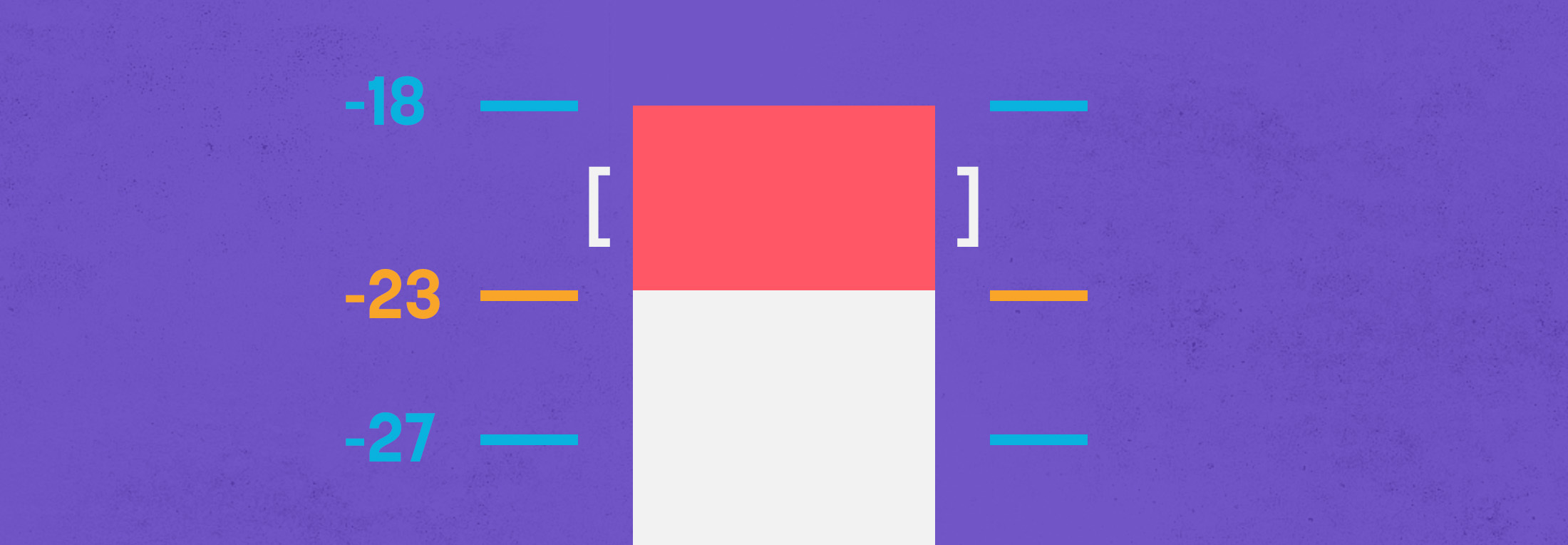

Two final examples that can apply in both mixing and mastering: Adding harmonics via saturation or excitation can be beneficial for both low and high frequencies. With bass, added harmonics can help create, or enhance, the “missing fundamental” illusion, which in turn can help it translate better on small speakers with limited low-frequency response. On the other hand, saturation of high frequencies can help smooth them out and prevent certain areas from becoming harsh.

Understand harmonics and fundamental frequencies in audio engineering

To recap, the fundamental frequency is what defines the musical pitch of any given note, and is the lowest frequency component we see when we view an instrument in something like RX, or another spectrum meter. Harmonics, on the other hand, fulfill multiple roles. Primarily, they define the timbre – or tonal quality – of a given sound. However, they also reinforce the pitch, or frequency, of the fundamental.

Armed with this knowledge, go out and play with harmonics! Whether via EQ or saturation, manipulating the fundamental-to-harmonic relationship can yield a wide palette of tonal colors to use during mixing and mastering. Use them to your advantage.