Essential Bass Compression Guide

Learn how to use compression on bass to create punchier, dynamic low end in your mix. In this guide, discover bass compression parameters, settings, and mistakes to avoid when compressing bass.

Learn more about Bass Compression in part 1 of this article.

Advanced considerations for setting bass compression

I’ve just given a basic primer for dialing in bass compression, but there are a few more things I’d like to cover before we move on to specific use-cases.

Sidechaining the bass for clarity

The kick drum and the bass often inhabit similar frequency ranges. They can clash if left to their own devices, muddying up the mix. Because of this phenomenon, many engineers will sidechain the bass to the kick. So, every time the kick hits, the compressor will cause the bass to duck a little bit in amplitude.

Start by sending your kick drum to an auxiliary channel with no output on it. This is commonly called a dead patch.

Kick routed to dead patch

Within the compressor you’re using on the bass, switch the sidechain input to the dead patch, like so.

Bass with kick sidechain compression

Now, when the kick hits, the bass will tamp down for a split second, letting the kick transient come through more.

Sometimes it pays to take this approach even farther. Perhaps we want to compress the bass for punch, and then duck it transparently when the kick hits. Here we might try a couple of tricks: series compression, and multiband compression.

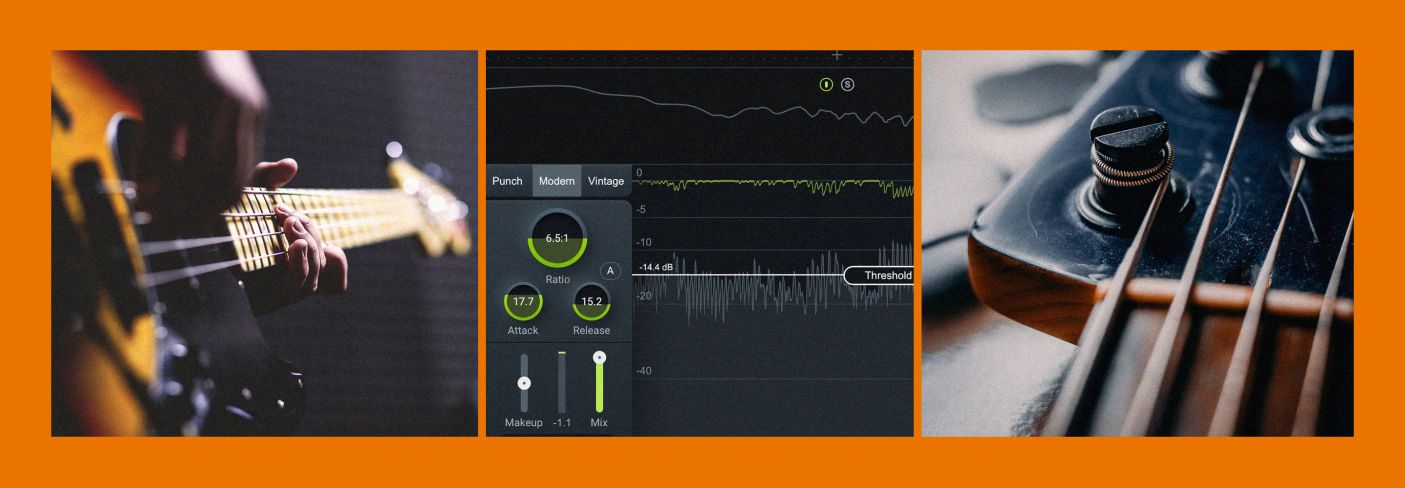

First, a compressor with punchy settings, as illustrated above.

Punchy bass compression settings in iZotope Neutron

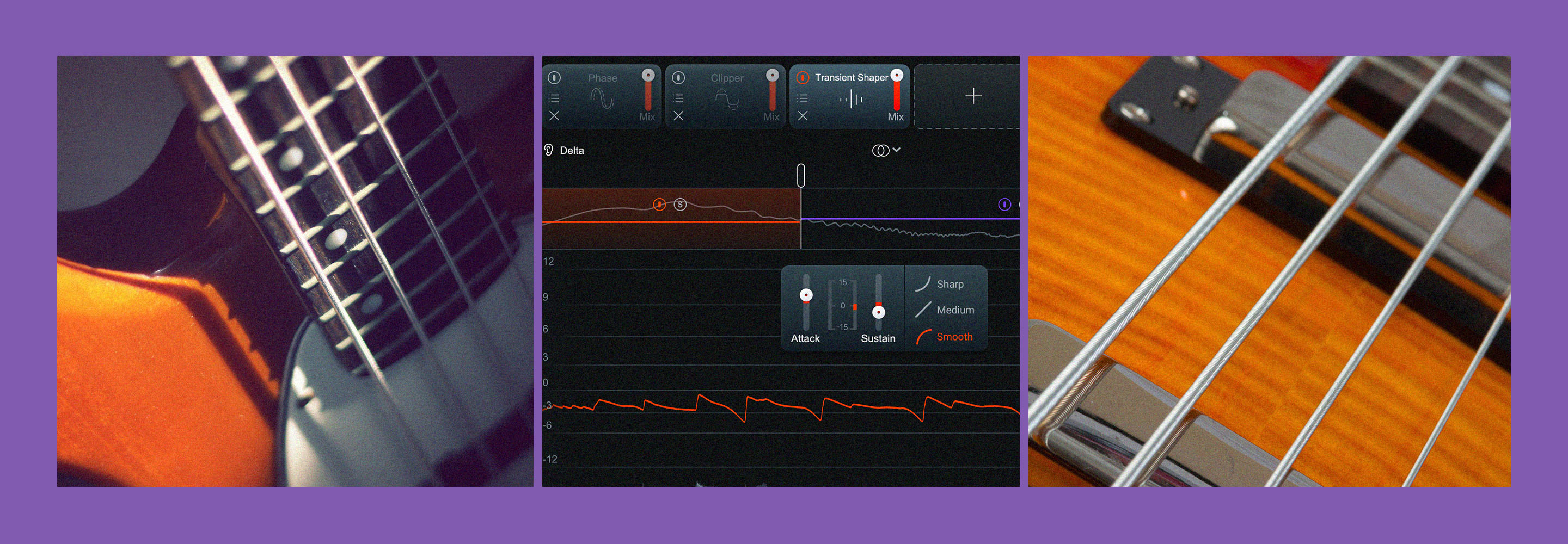

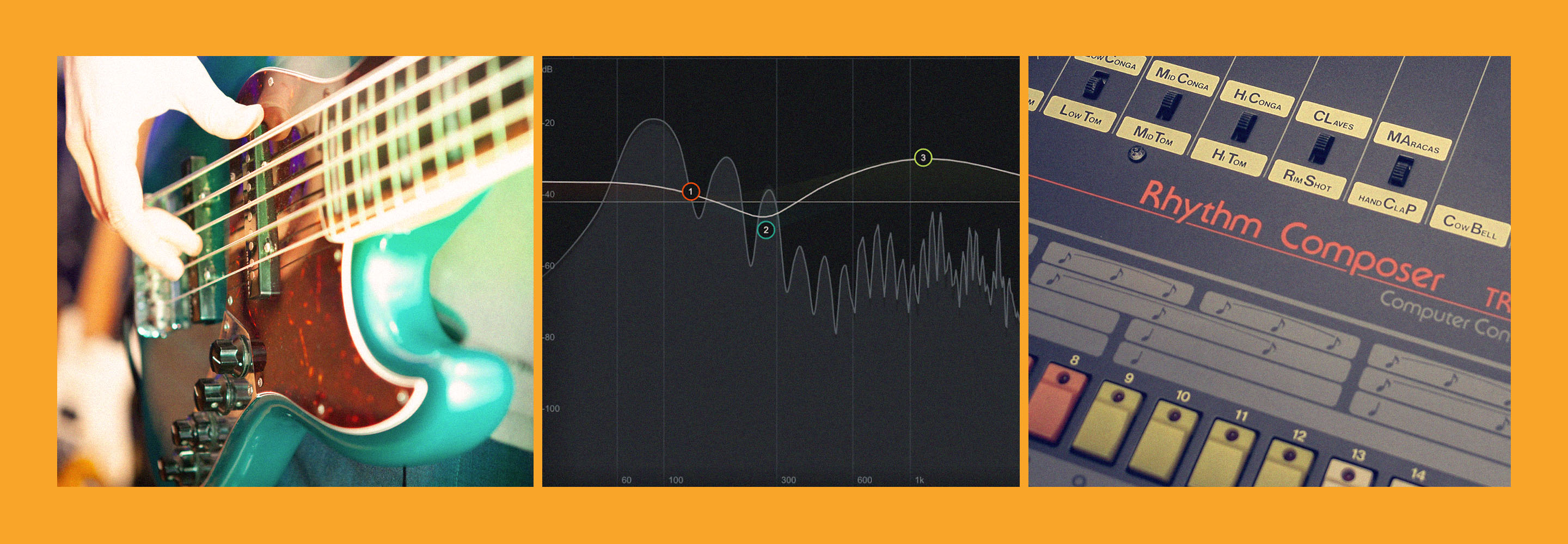

Then we use another compressor, and this is what we call series compression: two compressors, one fed into the other.

Next, the second compressor has a couple of special things going on.

Sidechained multiband compression in iZotope Neutron

First, the compressor is running in multiband; it’s only working on frequencies below 100 Hz or so. Second, the bass is sidechained to the kick, so the low frequencies duck ever-so-slightly when the kick hits.

The kick comes through, and the bass is punchy without sacrificing lows.

Sidechaining the bass for groove

Sometimes the whole bass part needs more attitude. It isn’t a matter of redefining the individual bass notes, but the phrases overall. When this is the case, you have two options, one involving compression, the other involving more drastic means.

The compression solution involves sidechaining the bass to another instrument in the mix. The process is similar to what I’ve described above, with a couple of tweaks.

First, try using the snare as your sidechain trigger, instead of the kick. This tends to add a more rolling, grooving feeling to the bass part. Secondly, play with slower attack and release times, so that the bass ducks down quite gradually when the snare hits, and raises in amplitude after the snare dies.

This method can work wonders for subtly altering the feel of the instrument.

Another way to improve the groove involves editing the part manually, phrase by phrase. That method is outside the scope of this article.

Color compression on bass

Finally, I wanted to provide more context on color compression for the bass. I already mentioned that iconic vintage compressors impart their own tone, as well as dynamics control. Here are three compressors you can use for that purpose:

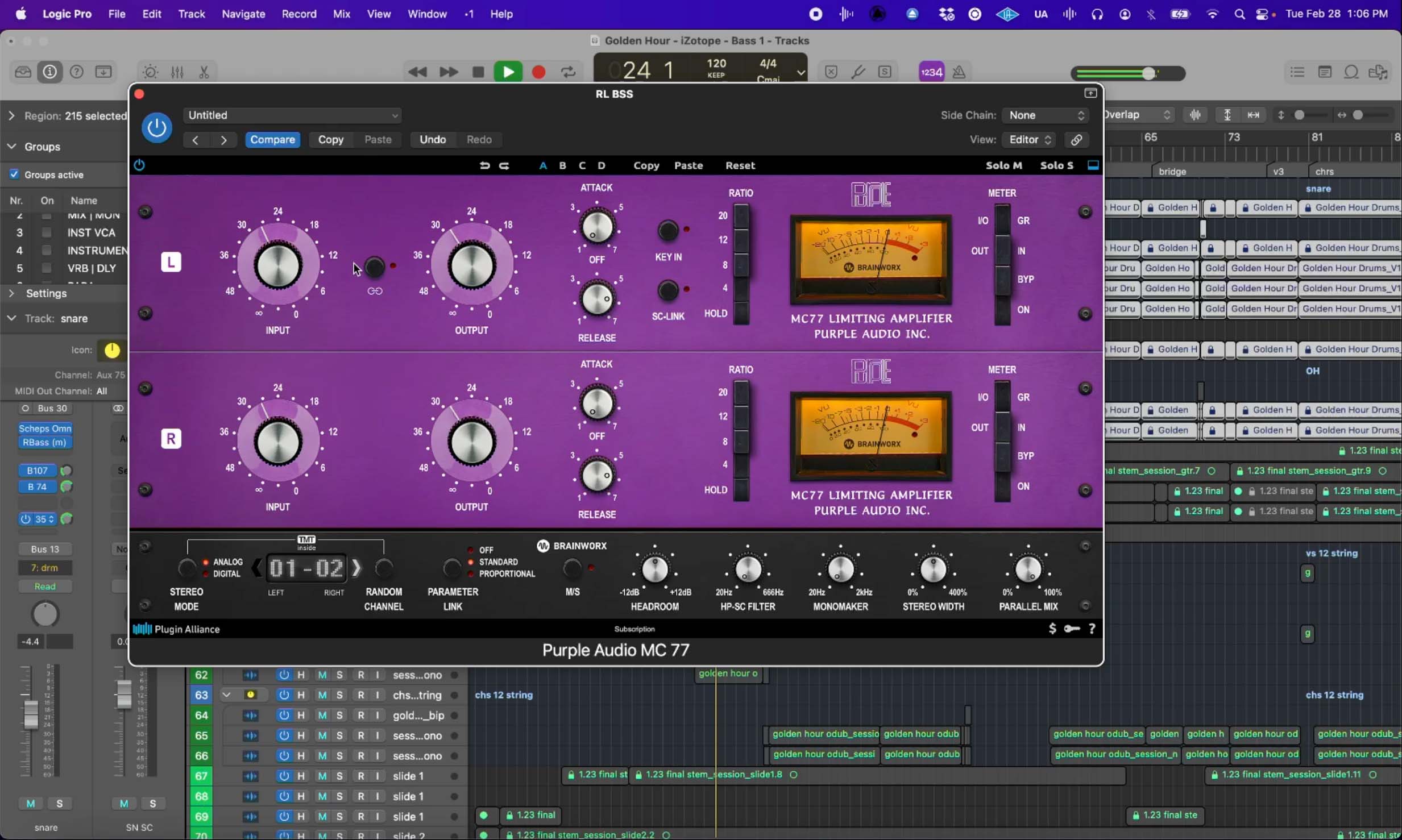

FET 76 style compressor

The Purple Audio MC77 is a FET compressor that has a lovely way of imparting aggression and punch to a sound.

Here’s the FET 76 with my starting point for bass.

Opto compressor

Optical compressors have a unique way of handling compression, often resulting in a smooth operation. The tube stages of classic opto gear also imparts a certain warmth to the sound. Here are a few choices for opto compressors in the Native Instruments family.

Variable-mu compressor

variable-mu compressors are also quite gentle and smooth, but their character is somewhat different to optical units. I would characterize them as less warm, and more glassy or creamy. They can be a perfect complement to a bass with too much going on in the low midrange. A mu compressor comes in the form of a NEOLD V76U73.

Punch compressor

iZotope Neutron has a compressor module called “Punch.” This isn’t a model of any existing compressor, but represents an interesting way of changing the envelope of the compressor’s behavior. Using it in series with other tools can approximate both the timing and the color of the aforementioned units, provided you know what you’re trying to achieve.

Genre bass compression settings

Here are some general guidelines for using compression on the bass in a few popular genres.

Motown-style funk bass

A slower attack, a faster release, a low ratio, and a threshold that doesn’t cut too much into the signal can accentuate the front end of the note nicely while adding smoothness to the part, all without messing up the bass player’s groove. Something like this could work nicely.

Motown bass compression settings in iZotope Neutron

Slap bass

Slap bass is deceptively hard to compress since the transients are so fast that you run the risk of doing damage to what makes them exciting. Neutron’s Punch compressor, set in multiband, can do a pretty good job of keeping the transients in line without making too much of a mess of the part.

Slap bass compression settings in iZotope Neutron

Metal bass

Metal bass primarily concerns itself with preserving the pick attack. Making sure you don’t hinder the pick attack means using a slower attack, and usually a fast to medium release is helpful for keeping the dynamics in line. Something like this could work.

Metal bass compression settings in iZotope Neutron

For more on mixing metal, check out the guide I wrote about mixing metal with Joe Barresi.

Rock bass

A classic combination on rock bass is an opto-style compressor to add an overall smoothness to the part, and an 1176 FET compressor to catch the peaks in a characterful manner. You can try the bx_opto compressor and the Purple Audio MC 77.

Rock bass compression settings in bx_Opto Compressor

Rock bass compression settings in Purple Audio MC 77

Neutron’s compressors also work in series for this purpose. The vintage compressor set to a punchier setting, followed into the punch compressor set to restrain dynamics can achieve a similar vibe.

Compressor module in iZotope Neutron

Rock bass compression settings with iZotope Neutron compressor's Punch mode

For more on mixing rock music, check out the rock n' roll mixing guide.

Experiment with the order of the compressors—sometimes the opto works better first, and sometimes the FET is the winner.

Please keep in mind that these are general guidelines. Much depends on the actual bass part in question. One thing’s for sure: you should familiarize yourself with material in your wheelhouse.

Mistakes to avoid when compressing the bass

Now that you have a handle on compressing bass, let’s cover a couple of pitfalls.

Over-compression is a major mistake to avoid. If you squeeze the life out of your bass, you’ll have a lifeless bass (obviously). More than that, you run the risk of making it feel smaller, flatter, and less groovy. Remember that the bass is the foundation for your tune. If you take away its groove or its spirit, you’ll make your production feel duller and less musical overall.

However, you can’t avoid overcompression if you can’t even hear it in the first place, which brings us to our second pitfall in mixing bass: many home-studio environments fail when it comes to reproducing bass accurately, simply due to the size constraints of the space. Standing waves cause badly placed resonant spots or dead spots in your room, and you can’t trust what you’re hearing.

Making matters worse, the two-way nearfield monitors available to most home engineers have a nasty habit of compressing when driven hard—and the bass can quickly drive sound systems hard. You can’t hear a problem like overcompression if your speakers are already compressing of their own accord.

Headphones could be the answer, provided you know how things translate from your headphones to the real world. Even the most expensive mastering-grade headphones have their own sonic imprint, either emphasizing or rolling off the bass; you have to account for this while working.

The only surefire way to get around this problem—other than having a professional space that’s been tuned and treated by a professional acoustician—is to know your monitoring intimately. Spend hours upon hours listening to all your favorite records from your childhood, making sure that the bass sounds exactly as you remember it from your youth. Having a few different monitoring solutions in the room can also help. I prefer to use one set of monitors, but I have three sets of cans I go between from time to time, and I’ll also listen to the sound coming out of my laptop speakers to see how it translates.

Get started compressing your bass

Hopefully this has been a good primer for you when it comes to compressing bass. Perhaps you won’t be so intimidated by this most vital of instruments anymore. Maybe you’re wondering “what about synth bass? How do you compress that?” Well, if that’s what’s on your mind, let us know! We’ll be happy to follow up with an article geared toward modern-day synthetic bass.

For now, many of these concepts apply, so feel free to get busy putting these tips to the test with a free demo of iZotope Neutron.

Learn more about Bass Compression in part 1 of this article.