9 Tips for Mixing if You're Not a Mix Engineer

Are you mixing a song for the first time? Discover these tips for getting a professional sounding mix when you’re not a mix engineer, including gain staging, track referencing, and more.

So you have an interest in mixing music. Maybe you make your own music, and necessity has become the mother of invention: “I gotta mix my song,” you say, “because no one else will!”

This is a common issue for many bedroom musicians and producers who don’t want to shell out for professional services but are looking for a polished sound. Some are even lured to the dark side, and become mixing engineers outright.

Here are nine tips for mixing songs if you’re not a mix engineer.

Want to try these tips yourself? Get started mixing with a free trial of iZotope

iZotope Music Production Suite Pro: Monthly

Music Production Suite 7

1. Learn about gain staging

Gain staging is the process of making sure the audio is set to an optimal level for the next processor in the chain in order to minimize noise and distortion. Unwanted distortion can wreak havoc on your mix, including nasty distortion that you definitely don’t want—such as unintentional clipping.

How mixers gain stage changes depends on a lot of factors, such as whether the mixer is using analog hardware, or how close the producer expects the mixer to stay to their vision.

You’re the producer in this scenario, however. You’re the one making the music.

When this is the case, what are you to do? Your session already has plug-ins, faders at various levels, and other things approaching a mix. Do you just reset all of that and start from the beginning?

No. Treat your finalized production as a rough mix. Save it as an independent session so you can go back to it if necessary. And then, try the following:

- Commit to all existing processing, so you don’t have to waste CPU on plug-ins or deal with MIDI (Each DAW has a different way of handling this, which you’ll have to research for yourself).

- Put

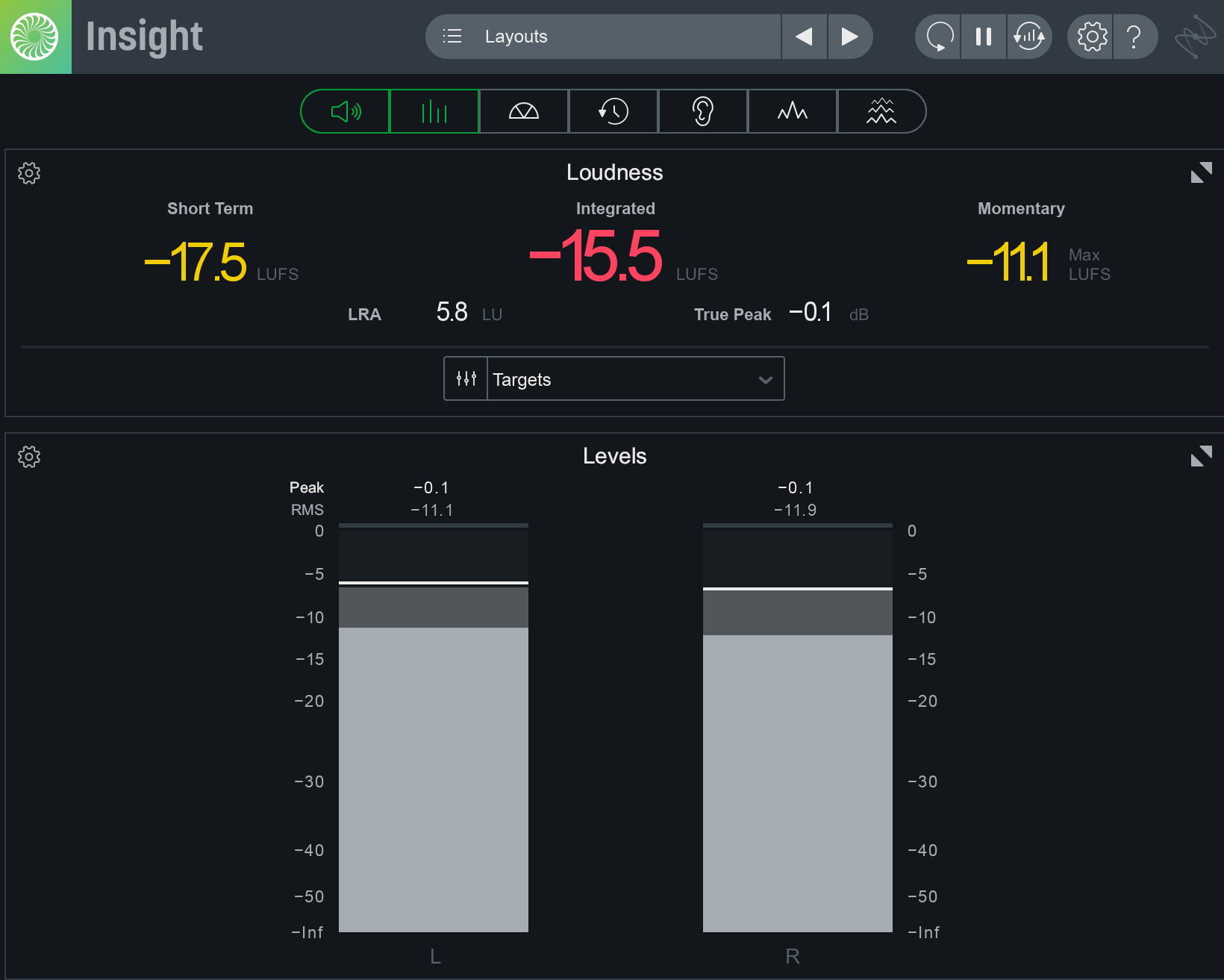

on your stereo output bus, and pay attention to the loudness meter.

on your stereo output bus, and pay attention to the loudness meter.

Insight 2

Insight 2 is a comprehensive metering and audio analysis plug-in that is a core component of award-winning post production houses, music studios, and broadcast facilities.

iZotope Insight loudness and level meters

- Select all your tracks, except the main stereo output bus.

- Pay attention to ONE of your faders and note its level.

- Hit play.

- Pull all selected faders down until the meter reads between -21 and -18 LUFS short term—a very safe, convervative level.

- That fader I told you to pay attention to? Note its new level and write down the difference on a piece of paper.

- Return all faders back to their original position (hopefully you still have them all selected, so it’s just a matter of moving your mouse once).

- Insert Relay as the first plug-in on each track, and set the gain in Relay by the difference. So, if you had to turn your faders down -6 dB to get to -21 LUFS in Insight, set the gain in Relay to -6 dB.

Here’s a video showing off the process. I’m using an intentionally loud, clipping, apple-loop based production I made in Logic Pro X. I’ve bounced my tracks in place, and I will gainstage accordingly in the video:

This last part is really helpful: having your faders near 0 gives you better precision on a logarithmic fader. If you follow this hack, your tracks will be at the same relative balance as your producer’s rough mix. It will also look the same as it did before you started, but you’ll have a ton of headroom for the mix process—which is important!

Bonus tip: If you want to go the extra mile, you’ll actually want to do this in a way where you can put all your faders at Unity gain (0 dB), which will help you get the most of your faders.

Writing out this process out is insanely complicated, so here’s another video to show you what I’m talking about:

At the end of this, you’ll notice that we had the same relative balance as when we started, but our short term loudness and headroom are in a much better spot to start a mix, and all the faders are at zero, which gives us a high degree of fader precision.

2. Choose your reference mixes

Mixing engineers use reference mixes to stay inspired and hit their targets. If you made a hip-hop track, there are certainly going to be other hip-hop tracks you want this mix to compete with.

Think of a Spotify playlist: when you make your own music, you would hope your songs would work well on a playlist with other material of the same genre or style.

This article references a previous version of Ozone. Learn about

Ozone 11 Advanced

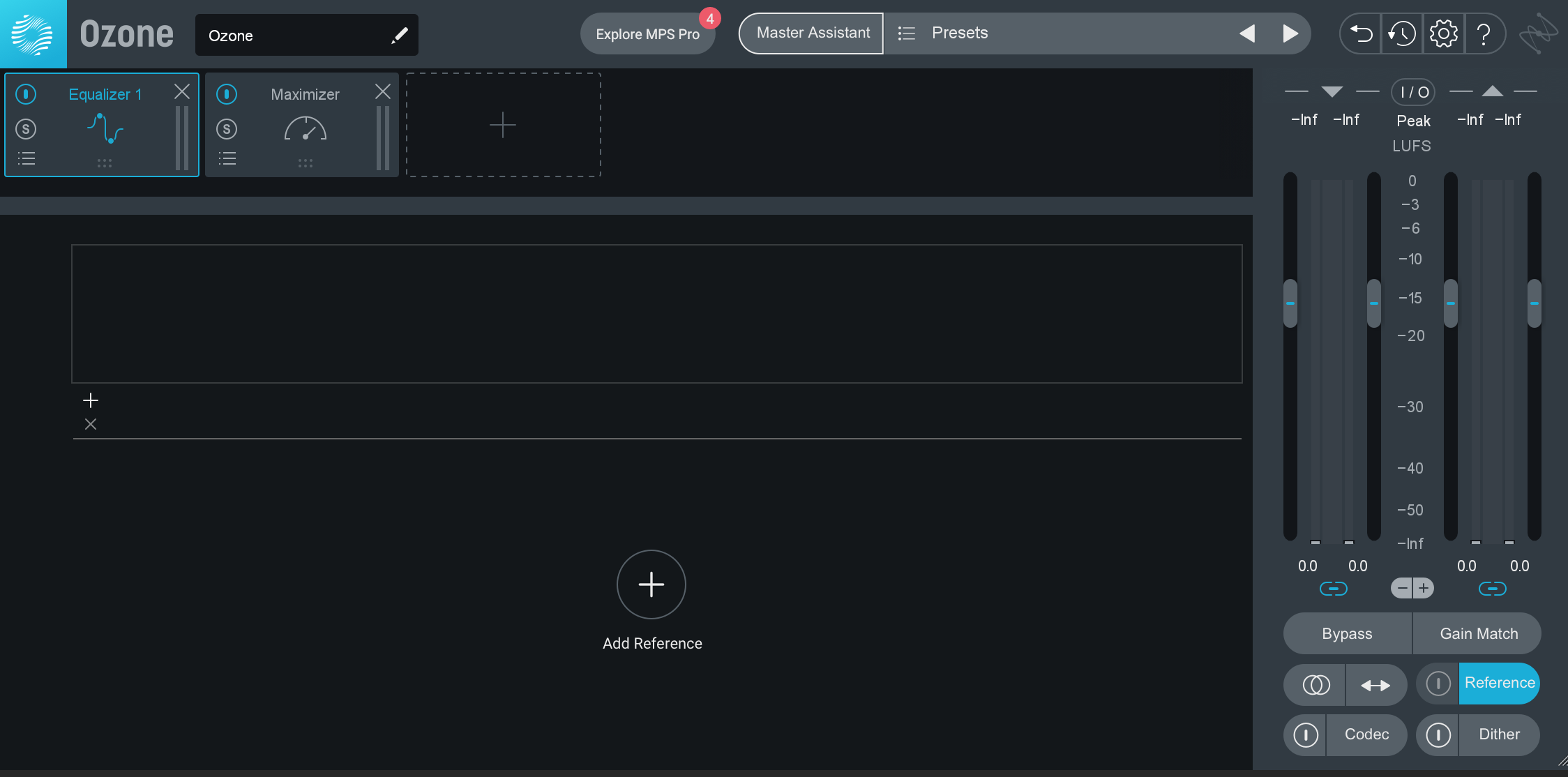

Once you select your reference songs, load iZotope Ozone onto your stereo output bus (before Insight), bypass all the default processing, and load your reference tracks into Ozone’s reference panel:

Add reference tracks in iZotope Ozone plug-in

Now you’ll be able to flip between your mix and the reference mixes as you go to glean inspiration. Make sure to level-match the masters to your mix!

Loaded reference tracks in iZotope Ozone

A word on files: your own music collection is a good place to start, but you may need to download a few songs as well. Be sure to secure a lossless file (.WAV or .AIFF) and avoid low-quality YouTube or SoundCloud streams that lack the details you’ll need for accurate comparison.

Try Bandcamp, Tidal, or Qobuz wherever possible, because those people actually seem to pay out their artists, unlike Spotify or Youtube, who don’t, and should be excoriated for this wherever possible, including in articles like this.

3. Make use of Tonal Balance Control

You’re not done with references yet: a third iZotope plug-in will help you get in the ballpark of your favorite tunes while mixing, and that plug-in is

Tonal Balance Control 2

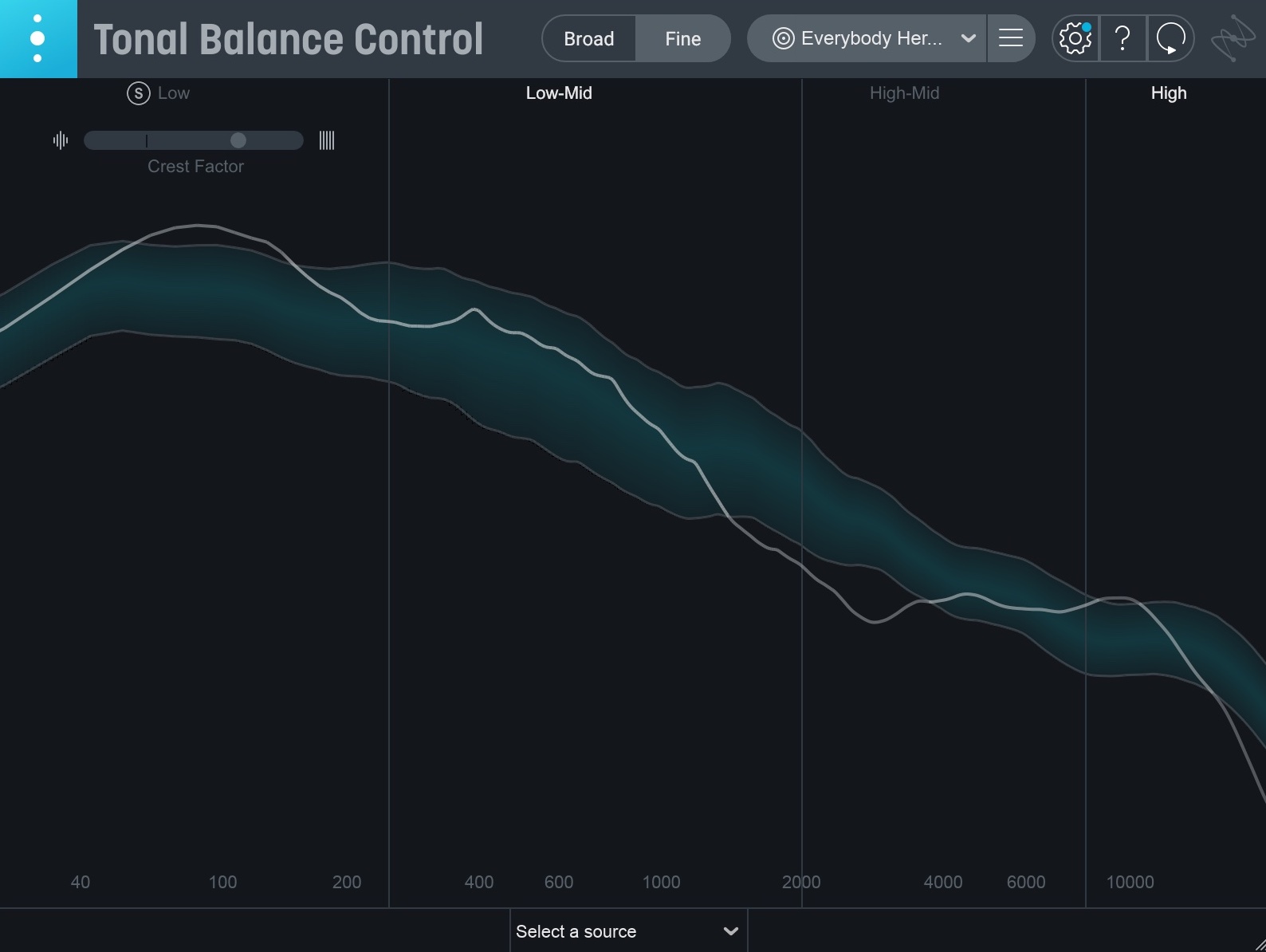

Tonal Balance Control offers a unique way to visualize reference tracks, displaying the frequency content of your mix against a target reference.

It just so happens you have a few target references—you got them in the last tip. Now you should load them into Tonal Balance Control, like so:

Custom iZotope Tonal Balance Control curve

Place Tonal Balance Control either before or after Insight, and you’ll find it comes in handy. While experienced engineers are able to pinpoint problematic frequencies with freakish accuracy, a new engineer can’t always interpret what their ears are telling them with such ease.

Tonal Balance Control is useful in judging what your mix needs more or less of, at least, in terms of frequency content. It's an objective check when your ears are still in-training or when you’re working in less-than-ideal acoustic environments (which, let's face it, many of us are).

Keep in mind that during sparse sections, like intros and solos, even a well-balanced song will move outside of the normal ranges. For this reason, denser parts of references are better for target comparison.

4. Get yourself a good static mix

Mixing is often about achieving balance, and in most cases, you can get to an initial balanced state with just two controls: level and panning. That’s it! So for 10 to 30 minutes at the start of your mix, forget about analog-modeled compressors, dynamic EQs, and all of the other fun tools in your arsenal and return to the basics.

Keep in mind that it doesn’t matter so much what each individual track sounds like, but rather how everything fits together in context. This is why we often dissuade people from mixing in solo over long periods of time. Also bear in mind that “balance” doesn’t necessarily mean “everything equally loud.” Some of the most interesting mixes have unusual sounds pushed to the front, or intriguing sounds that you really have to lean in to hear. This process is called the static mix.

It’s worth noting that iZotope's mixing plug-in,

Neutron

5. Learn about frequency masking

One of the hardest things about mixing is figuring out what should clash and what shouldn’t. That’s right, some things should absolutely clash in a mix. You don’t just carve out frequencies to sit other instruments in there and expect a good mix to happen—sometimes a bass guitar rubbing against a distorted guitar gives the needed density to a mix.

But often things clash in a bad way, and even though you did your best with your producer hat on, in the mixing phase, you’ll listen to references and see that actually your vocal is getting buried, or your kick drum is obfuscated by the bass–this is also known as frequency masking.

Luckily iZotope has two great starter tools to help with this. The first is Neutron, which has an Unmask module to help you figure out if two sources are clashing in a bad way. Read more about Neutron’s Unmask module.

The other tool is Nectar —specifically its Unmask feature, which does some of the heavy lifting for you, automatically moving an offending track out of the way of your selected track. Here’s a video to show you how it works.

6. Understand compression

You probably heard about compression in audio mixing, the tool every engineer loves to talk about. Don’t use it just because you think you should—that would be a mistake. Instead, take the time to learn what compressors do, and the different ways they can help your mix.

I’ve written a ton of material about compressors on this website. Search my last name (if you can spell it: “Messitte”) and compression and you’ll find a lot. I’ll boil down some things you should know below:

- Compression can be used to restrain a part that is wildly too dynamic, so you don’t have to mess with automation for every single bit of the song.

- Compression can bolster a sense of groove where there wasn’t a groove before.

- Compression can cohere several parts together into something more pleasing (this is called “glue”).

- Compression can change the tonal balance of a song due to how it’s compressing (make vocals sound more sibilant, or thicken them up).

- Compression can change the overall color of a sound by virtue of its circuit or modeled-circuit path.

- Compression can enhance, or tame, transients and sustain.

That’s a lot to keep in mind, and we haven’t even covered multiband compression, dynamic EQ, or iZotope’s spectral processing which dynamically shapes bands of frequencies.

Neutron

Nectar 3 Plus

Ozone Advanced

If you’re looking for recommendations as to which compressors to use, well, that’s quite personal, but I can give you my preferences:

Though I’ll use all of them, Ozone is my favorite of the lot, and I use it often when I want clean, tweakable compression. If you’re into any of iZotope’s sister companies, you’ll find some great compressors there as well. Native Instruments’ Guitar Rig has a tube compressor that absolutely slays for color on drums, especially in parallel. Plugin Alliance, newly brought into the fold, carries a veritable ton of colorful compressors, including a great 1176 clone in the Purple Audio MC77, and an SSL-ish bus compressor in the Bx_Townhouse.

7. Abide by the law of contrast

Though by no means a recognized rule, following the law of contrast will serve you well. What this means is that no one effect is the key to unlocking your mixes: instead, it’s what any effect stands in opposition to that makes the difference.

Reverb is a great example of this—which surely you’re going to add to your mix. But reverb will get you nowhere without dry material standing in contrast to it. It is the contrast between dry and wet elements that make some things close and others far away, not the effect itself. If too many channels are sent to a reverb, you will lose all sense of detail and shape, whereas too many dry elements will come off as flat and boring. You can read more about this in my article about mix depth.

Mixing benefits from a sense of contrast. If you want a reverberant feel, some sounds need to be dry to show the difference. If you want depth, make one or two instruments bright and leave the rest darker in tone. If you want the chorus to really hit hard, you have to pare back the verse. It’s difficult to distinguish space or brightness or any other characteristic if there isn’t something else to compare it to.

8. Listen at healthy levels

Really, this tip applies to all stages of the music creation process, but it’s particularly important in mixing. It can take a while to mix a song—sometimes it takes a few hours, but it can easily stretch out to a day or more, particularly for those new to the sport.

If you crank things up at an early stage, subs woofing and all, you will quickly tire your ears and lose perspective on the mix. I imagine you’ve heard and read many cautionary tales about this topic before, so I won’t go into detail except to provide you with our article on listening fatigue and how to prevent it.

That being said, it can be useful to bring up your playback level now and then—this will reveal the harsh frequencies, particularly in the mids and highs. But do this sparingly. I’d even go as far as taking a break after to reset your ears.

I’m a bit of a freak about this. Every day I go to mix I make sure I have my monitors calibrated to play back my reference mixes at 79 dB SPL, C-weighted, in my room. I listen to some references to tune my ears for the day, and then I get to work, keeping my levels and monitoring in check.

This means if I’m mixing at -18 LUFS, my monitors will be set to play -18 LUFs back at 79 dB SPL. When I want to blast, I know what setting on my monitor controller will take me up to 85 SPL. When I check in headphones—or mix in headphones, as is more and more the case with a small child in the house—I have set levels for that as well, to make sure I don’t tire.

Adopt practices like these to save your hearing and save your mind.

9. Don’t even think about mastering until you’re happy with the mix

If you’re reading this, you’re probably at the beginning of your journey mixing music, which means you honestly shouldn’t think about audio mastering yet. Mixing is hard enough without worrying about the game of subtlety and compromise that mastering necessitates.

Most professional mixing engineers work with mastering engineers for a reason—it gives them a safety net of sorts. The engineers that do tackle both disciplines at the same time have done so with an abundance of caution, experience, and confidence: getting things balanced, moving, grooving, loud, but not harsh, is really hard to do near digital zero.

So don’t think about mastering until you’re happy with the mix—and when you do plan on releasing the track, see about hiring a professional mastering engineer. At least at first.

However, you can use iZotope tools to give you a ballpark estimate of how your mix would sound in the real world, at real-world levels, with moves made to help with balance and translation.

Ozone has a Mastering Assistant which does a really good job at that. You tell it a few basic things about how you want your final product to compete, and it will supply a balanced, translatable result at healthy levels.

However, it will not QC your mix for errors that escape your listening environment—like clicks or pops—nor will it help an EP of material flow seamlessly. It will not supply you with perfectly topped and tailed files at various sample rates and formats. And it won’t call you up to say “you don’t have to be so cagey with things in the 3 kHz region,” or “you did a really good job with this one.”

Start mixing your track

Remember that making the leap to engineering from production is a matter of balance and mindset. In the mixer’s chair, you leave production behind and set upon a new task of goals. Keep these goals in mind, follow the roadmap laid out above, and you should do fine.

And if you haven't already, check out iZotope's suite of mixing plug-ins that can get you started on the right path as a mix engineer.