18 Tips for Running a Great Recording Session

Whether you're looking for client-facing or technical tips on how to run a recording session, or just how to work with singers and instrumentalists, let this be your guide.

Right now, if you’re remotely familiar with this topic, you’re probably hoping I have something to offer besides “keep your studio clean” and “have coffee ready for the clients.” I know I was sick of those chestnuts when I found myself knee-deep in tutorials.

I’ll tell you upfront that “keep your studio clean” is tip number one, but don’t skip over it—you might find the perspective interesting. As for coffee, it’s never mentioned, though tea makes an appearance.

All of these tips comprise my approach to recording in studios, whether I’m visiting someone else’s lair, recording in my own rooms, or orchestrating audio capture on location. It is my hope that these suggestions will provide a holistic and practical approach to keep you and your clients happy. Let's start with the technical tips.

1. Keep the Space Clean

If you've ever saved up money to record in a studio, you know there's nothing worse than showing up to a dingy, dirty space. It’s a common occurrence in today’s world of home studios and intern-based maintenance staff, but you, as the host, have the power to change this.

Get in the practice of cleaning your space beforehand, because a messy studio telegraphs that you don't care. All the vintage gear in the world will not impress if it’s caked in dust.

Also, cleaning the space is not only good for your clients (not to mention, your gear)—it’s good for you; the more you do it, the more it will become a ritual that readies the mind and prepares the body. Think of it as Zen and the Art of Pushing a Broom: The practice will help you achieve readiness, and therefore, efficiency.

Do be careful not to use overly-scented products, as they can aggravate some singers’ sinuses. I’ve also found they tend to raise psychological alarms. “Why am I smelling Febreze?” is a thought usually followed by, “…what happened in here last night?”

It’s about distractions: You don't want to cause any.

2. Get Your Files in Order

As the environs of your studio should remain tidy, so should your file management. Your recording system needs to be rock-solid and checked for reliability beforehand. Any disk-utility or defragging tasks should be handled well before a client comes in. Likewise, your operating system should be learned, trusted, and dependable—and never upgrade operating systems right before a session!

By the time your client arrives, you should have the appropriate project-folder established and named. Every track should be labeled consistently as you record, clearly denoting the instrument, the take, and the date. The same goes for exports.

This is for your records, but if you're recording sound on-location for EFP, check with a higher-up about how the files should look. There might be specific requirements. If no one seems in charge, contact your peers down the pipeline: The mixing engineer, re-recording engineer, or the post-production sound designer will have opinions. Your workflow needs to complement theirs, because nothing is worse than hunting for takes when all the files are labeled "a7963h800-1," “a7963h800-2,” or some other combo of computerized argot.

3. Know the Session Parameters Beforehand

Try to get as much information about file-formats, DAWs used in pre-production, and export expectations before the session. At the very least, ask the producer, artist, or production manager to tell you what sample rate they prefer. Failure to do so can result in headaches down the line.

For instance, a friend of mine recently received multiple 32-bit/192 kHz files of a fifteen-second vocoder overdub. The original session was 44.1 kHz. Obviously the engineer hadn't thought to check beforehand. The result? An unhappy mix-engineer: My buddy felt compelled to audition multiple SRC algorithms for a whopping 15 seconds of ancillary material. That’s time he could’ve easily spent on the mix itself—or, you know, with his family.

4. Archive Everything

Make sure you keep and archive every file for every session; do not delete any material, or throw away any hard disk. If you run out of space, buy more hard drives. Keep your hard drives clean and test their reliability on a regular basis. If they seem to be acting up, back up the hard drives.

You never know when artists will come back to you for their tracks; I’ve had bands ask for their recordings years later. You don't want to be in a position of telling them the tracks are gone. If they are, you probably won’t be rehired.

5. Go with Gear You Know

Now is not the moment to test out that new preamp. Likewise, if you’re guest-engineering at a facility with a vintage RCA 44—and you’ve never used one before—sorry, now's not a good time.

Studio time is quite expensive for clients, and it can go sideways very quickly for the engineer. Part of your job is cutting the quickest path to the best possible sound. Go with the tools you know, using the techniques you’ve perfected over your career.

Some exceptions: If you're guesting in a space, and you trust the house engineer's recommendation, then go for it; this engineer might be paving the quickest path to the best sound. Also, should the producer/artist encourage experimentation, then oblige—as long as they’re paying for the session!

Neumann Condenser Microphone in a Recording Studio | Photo via Pexels

6. If You’re In an Unfamiliar Space, Learn It

You might be called upon to work in unfamiliar environments, be they locations (concert halls, film shoots), or studios. Be sure to sonically investigate these environments before the client shows up.

In a new studio, make sure to familiarize yourself with the room’s signal flow; the console (if there is one), headphone amps, wall-mounted XLR panels—anything that pipes sound should be reviewed. Bring a pen and legal pad to jot down notes. If you’re recording on location, be on the lookout for available power supplies, and claim a corner to charge your spare batteries.

Next you should listen to the recording environment’s acoustics. You can use tone generators and various meters if you have hours to kill and an anal-retentive streak. A simple conversation with someone while walking around the room will get the job done also; just keep your ear open for sonic peculiarities as you walk about, notating them for further reference (i.e., if the corner has a big frequency bump at 440 Hz, it’s probably not a good idea to record a song in Ab major in that corner). Clap your hands, hoot, holler, and make any sort of noise that will help you suss out flutter echoes, unpleasant reverberations, or anything else you might want to deaden up.

Control rooms are supposed to sound perfect, and yet they all seem to sound different. Therefore, familiarize yourself with the room’s acoustics and monitoring setup. I use a reference disc chock-full of music from my childhood, playing the tracks through various monitors. I walk around, listen, and ask myself, “Does this sound like my childhood?” If not, what’s different? Does it sound duller than I remember? Do the dynamics seem different? I jot my findings in my notepad and refer back to them when making decisions about the specificities of what I’m hearing during a recording session. If the singer sounds bright, but my notes indicate it’s a bright room, I might not change anything.

7. On a Shoestring Budget, Go for Good over Great

If you've had an audio education, you know how to get good sounds on many instruments. If you haven’t, there are excellent books on the subject, and plenty of opportunities to practice on yourself and friends till the basics are ingrained.

Remember that studio time is a luxury these days, so sessions are never as long as they need to be. Unless you’re working with a rich, inquisitive client, now is not the time to reinvent the wheel. However, if you happen to discover a unique sound while recording, definitely grab it and put it to tape. Just don’t waste time chasing your own tail in getting it.

This advice might seem counter-intuitive, but here’s the thing: Unless your technique is actively bad, the magic tends to come from the performer—not the gear. No amount of microphone sizzle is going to make up for a lousy vibe.

8. Provide a Great Headphone Mix

Always take the time to set up a good headphone mix for the client. When setting up that mix, listen through their headphones and, if possible, their headphone amp. This way you’ll know exactly what they're hearing.

The performer’s headphone mix is arguably more important than what you hear coming out of the monitors, because they’re the ones delivering the goods. Also, have a reverb and a delay a click away if they want to hear it.

Provide a great headphone mix | Photo source

9. Visualize Murphy’s Law—and Make Peace with Murphy

Before I do a session, I usually know who, where, and what I’m recording, so I do the following exercise to stay vigilant:

If the microphone quits on me, what's my backup plan? If the preamp cramps out, what's the next best pre? If the patchbay goes down, what's the quickest way forward? As a faulty cable is often the culprit, will I have a spare on hand?

What if the computer goes down; how's my laptop running these days? Is my portable interface in working order? If that goes down, where's the field-recorder, and do I have a spare SD card for it?

This list goes beyond the technical: If the singer shows up inebriated, how do I handle it? If the producer and the artist have a fight, how will I settle it? Experience comes into play here, both overarching and specific: Is this the client who never sings on key? Should I have a harmonizer setup on the session for playback, leveled so that she won't know it's there, but the producer will find it listenable? And so on and so forth, until I've considered everything.

Don’t become paranoid in doing this; there's no need to be worried something will go wrong, because something will always go wrong (maybe that says more about me than you). But that's okay! In failure, there can be magic.

An example: A faulty cable once introduced arrhythmic pops during a take. Fortunately for me, the artist loved the sound. Of course, I swapped the cable anyway—we needed to get going—but chopped and edited, the pops became a dominant rhythm in the track.

Don't be paranoid. Be vigilant, accepting, and calm. When something does go wrong, you'll instinctively know the next and fastest move, even if you hadn't anticipated it.

10. Set Aside Time After the Session for Mix-Down

The client always wants to hear what they've just done. They also want to hear themselves in the best light. The best compromise is to leave yourself an hour or two after the session. Take a quick break, put up a good rough mix, and send it over within the day. You might also get yourself a new mix-client in the process; it’s certainly happened to me.

Client-Facing Tips

11. Cater Your Personality to the Personalities in the Room

On a good day, forty percent of this job is technical. The rest is psychological. A good deal of it is psychological manipulation. Here’s an example:

I’ve found that no matter the studio, clients often have a horror story about getting there, usually explaining why they were late. How I listen to this story invariably affects the quality of the session; if I'm brusque, unfeeling, and down-to-business, the performance is stunted, but if I take the time to listen and share (but not over-share), the resulting material is always stronger. Here’s where hot tea on a cold day goes a long way. Ironically, going straight to business ends up being less efficient because the artist is still stressed.

Think of it this way: Sometimes you have to pull out 3 kHz to make the vocal sound less nasal—and sometimes you have to nod your head and say “that’s awful” to even get the performer to the mic.

Also, remember that your client-base will be varied. I have worked with populations as disparate as secular scientists and Hassidic punk rockers, but there is always a common link between them: the amount of attention and respect they’re entitled to.

Your job is to orchestrate personalities, to leverage their quirks and mitigate their foibles, all in service of their material. Under no circumstances should you contribute to chaos.

Thus, it's a good idea to take a long look in the mental mirror and see what makes you tick. Don’t change who you are; that’s impossible. Instead, understand your quirks—your foibles—and then use them to your advantage.

For instance, I'm the voluble type, so here’s what I do: I pretend I have a two-second latency built in, during which I can mute anything I’m about to say that could be construed as untoward.

12. Don't Have Intern-Face*

What’s “intern-face?” Chances are you've had it, and if you've been to someone else's studio, you've seen it. It's a vacant smile that's desperate to please, a distrustful exuberance that only gums up proceedings.

A studio-intern once proudly told my (vegetarian) client the following: "They didn't have Pad Thai with tofu—so I got you chicken!!!" Guess what? He had intern-face. He also didn't have a job the next day (don’t worry, I didn’t fire him).

You don't want intern-face because it engenders the opposite of confidence. Look in the mirror and make a big goofy smile; tell yourself exactly what you don’t want to hear in the most ineptly cheerful tone you can muster. Now you know what you look like with intern-face. Now you know what intern-face feels like on your face.

Don’t have intern-face—especially if you’re an intern!

(*I call it “intern-face” because I’ve predominantly seen it on interns. This is not to say, however, that all interns have “intern face”—some of my best friends are faceless interns…)

13. Know Your Role

Your role changes with the people in the room. If there's no producer present, and the vibe feels right, the artist might need you to suss out the best take. If the artist is cocksure, stay out of the way. A voice-over session will usually involve a director, so you better not step into that roll, or else you’ll undermine the director’s job, and what’s worse, confuse the talent.

…Unless the director asks for your opinion, which believe me, can happen—it actually happens all the time, because good directors are collaborative. The point is you need to read the situation and adjust your role accordingly.

14. Find Ways To Keep Yourself Motivated

There comes a moment in every session where you just want it to be over. To do your best work, you need to find ways to trick yourself out of this moment. I find that more than money, more than the big bowl of cereal I'll eat after the session, falling in love with some part of the proceedings keeps me motivated.

Key into some aspect of what you're recording and be grateful for its existence. If you don't like the song, try to admire the singer's voice. If you don't like the voice, admire the chain picking up the voice, the clarity of the microphone, the way you've angled the capsule to offset sibilance. The point is to stay engaged, because an engaged engineer is a careful, meticulous, and trustworthy servant.

15. Let Things Get Daffy, But Keep an Even Hand

Remember how I said that recording sessions have a tendency to go sidewise? Sometimes that's a good thing. I don't know why—maybe it's the vulnerability inherent to performing—but some of the deepest belly laughs are to be had in a recording session. As an engineer, you might think this is counterproductive, because giggles ruin good takes. You might want to kill the banter and “encourage professionalism.”

Fight this urge. It puts you in opposition to the creative flow, and what’s more, you're denying what might end up becoming great outtakes to be included later on, as well as a feeling of joy which helps any move session along. You’re also undermining the bond you establish with the client.

However, sometimes you do need to shut it down. If you've bookended one session with another, and you're legitimately running out of time, gently move the session along. Similarly, if you're the one causing the disruption, that's not good. A case of the giggles on your part is a great excuse for a bathroom break.

On occasion, the joking could go too far and make someone uncomfortable. Pull the offender aside and reassure them that, while you’re sure it was a joke, the talent might not take it that way. Don’t launch into a diatribe; you're here to serve the session, not a set of beliefs. There is a time and place for conversations regarding important issues, but this isn't it.

3 Quick, Concrete Tips for Working with Singers and Instrumentalists

16. Do Not Exhaust a Singer by Testing Mics

This will wear out their chops. There is no substitute for vibe, no matter how vintage the Neumann is. However, if you’re working on an album’s worth of material with a client—and if you have an extensive mic collection—it might pay to experiment with different combinations. Just don’t think you’ll get a great vocal if you record right after.

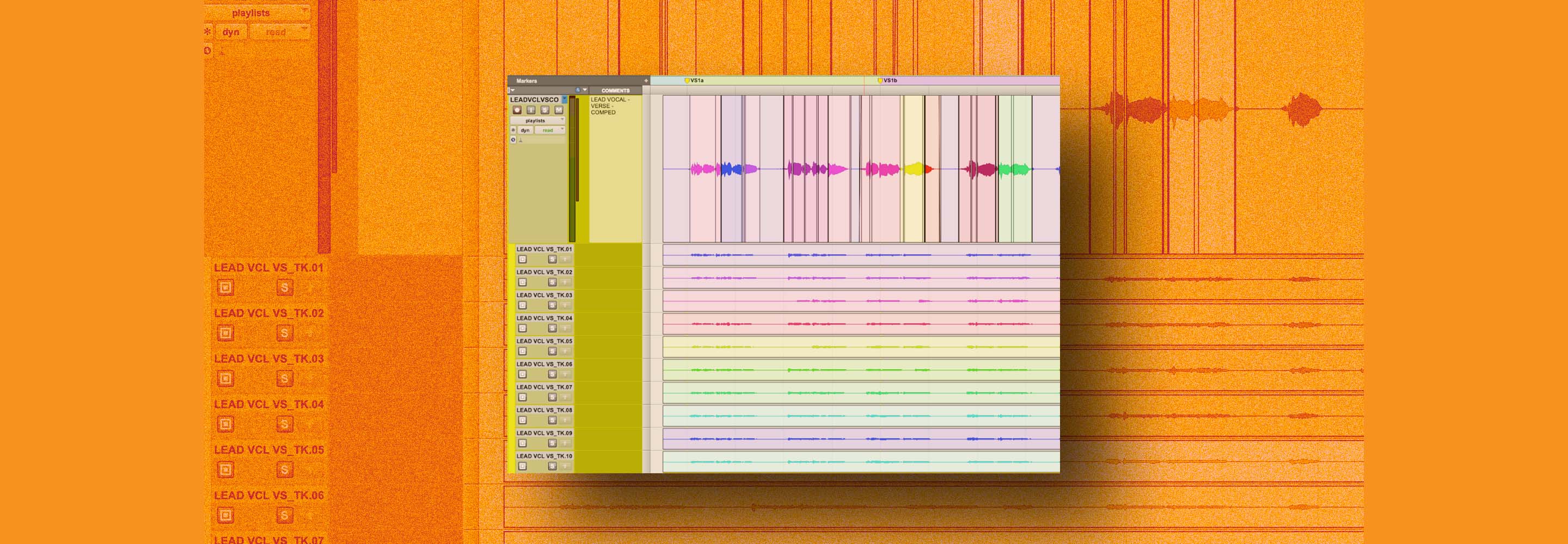

17. Learn to Comp Quickly

Whatever the instrument, you should develop the skill of comping takes on the fly. Don’t be afraid to use your judgment as what constitutes the best take; they are paying you for this as much as anything, and you want performers to hear the best version of themselves upon playback. This instills self-confidence.

18. The Old Misdirect

If you’re not getting the take you want out of a performer, but you don’t know what’s missing, try this old director’s trick. At the very least, it will elicit something different.

Just say this: “That was great! Can you do another take, but this time...ah, just do another take.”

Say this as though you’re interrupting yourself. And let it hang there. The performer might be confused. They might say, “This time, do what?”

If that happens, respond with, “I forgot—but let’s do another take!”

In this circumstance, yes, you are trying to confuse the performer. But if you go about this politely, the confusion will work to everyone’s advantage. The artist will attempt something different because of how you asked. Not knowing what you wanted will keep them on their toes. Being polite about the request will ensure no weirdness in the asking.

Nine times out of ten, when the performer tries something different in the subsequent take, you’ll get something worthy of keeping or exploring further.

These are all the tips I have for you at the moment, but if you like what you see here, let us know; we can always drum up some more.