11 Tips for Mixing and Sound-Designing a Fiction Podcast

Get advice for mixing and sound-designing podcasts from engineer Vincent Cacchione, composer Jon Bernstein, and the co-creator and mixing engineer from behind Welcome to Night Vale, Joseph Fink.

Podcasts seems ubiquitous these days—indeed, people have been talking about the podcast revolution since 2014, when Serial took the medium mainstream. A lesser-known quantity is the fictional podcast, a movement harkening back to the old-timey radio of my father’s day. For the uninitiated, think of The Thing on the Fourble Board crossed with the production values of Radiolab, and you’ll get the idea.

What does this mean for you, the working audio engineer? A creatively satisfying way to apply your skills.

Yes, opportunities abound—many networks and companies are pushing for narrative fictional content. Gimlet just offered their second such series, for starters. But one cannot speak of fictional podcasting without mentioning Night Vale Presents, the powerhouse behind Alice Isn’t Dead (final season premiering this Spring), The Orbiting Human Circus, It Makes a Sound, and of course, Welcome to Night Vale.

Certainly, I cannot do so. That’s why I sought out engineers, creators, and composers at the company to walk us through the finer points of sound designing a work of audio fiction. What follows are tips from engineer Vincent Cacchione (Sound and Circus), composer Jon Bernstein (Night Vale and Alice), and, last but not least, Joseph Fink, the co-creator and mixing engineer behind Welcome to Night Vale.

With their guidance, we present eleven tips broken down into two categories: technical tips, and general advice.

Technical Tips

1. If you’re recording the audio, try some experimentation

Recording fictional podcasts differs from the stuff of Serial. The goal in non-fictional podcasts is often to remain invisible; this means the bulk of your work comprises editing, noise-reducing with a tool like RX 6, and leveling sentences for intelligibility.

In fictional podcasting, your objective is to serve the story, which allows you creative liberties in recording. Says engineer Vincent Cacchione, “When you get a bunch of actors in a room, you get to the heart of creating the moment.”

Capturing scenes—not phone calls or interviews—gives you room to “think more creatively about what is this person’s relationship the microphone.” You can ask yourself questions like, “If the microphone is our picture for this moment in the narrative, how can we embellish that in the recording itself?”

Vincent advises to play with space, action, and other elements in front of the microphone—as long as it serves the scene. “I would sacrifice isolation to have a vibrant live scene any day of the week,” he told me. “If there are five actors in a scene, and if it’s possible to have all five actors in the room, do it.”

2. Stay organized

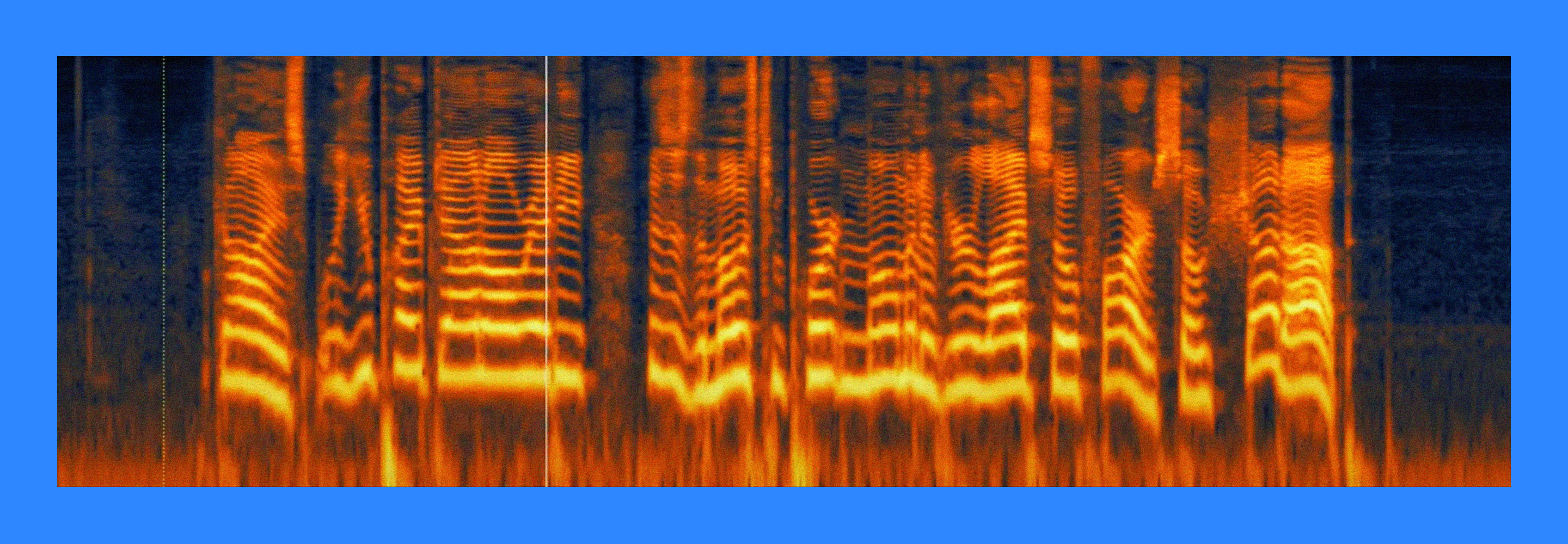

This is a creative endeavor—but that doesn’t mean you throw good mix-hygiene out the window. On the contrary, you might wind up with a large track-count due to the number of sound effects, music tracks, and voices involved. This, for example, is what a screenshot of my average session for a narrative fictional podcast looks like, composed in Logic.

That’s more than a hundred tracks.

Vincent’s advice? “It’s important to take a second—even if you’re trucking with creative stuff—and slow down to keep yourself organized. Because it just sucks when you’re at the end and looking at a million things and none of it makes any sense.”

See this article for tips on how to manage a large session in your DAW.

This follows into our next tip, which is…

3. Clean up noisy audio

As budget is key, vocals can sometimes be recorded in less-than-perfect environs. Conversely, sometimes the talent might not be hip to best microphone practices. So keep in mind that a little denoising can be in order.

“I don’t record everything I mix,” Vincent told me. “A lot of the stuff people send me is hissy, or right next to a fan.” So you do still have to de-noise, within reason.

Like many in his field, Vincent uses RX. “I find it’s really useful for getting rid of some garbage noise.”

4. Combine music and sound effects to serve the story

Serving the story is vital to the work, never more so than in matters of music and sound effects. Getting the perfect ratio of these elements—and the perfect feel for the music—is paramount, as this combination of sound can easily change the mood of a given scene.

Look to the diversity of Night Vale Presents for examples: Shows like Alice Isn’t Dead or It Makes a Sound employ sound effects, while Welcome to Night Vale relies mostly on music as its contrapuntal force.

“I knew I wasn’t interested in doing something that was sound-effects heavy,” says Joseph Fink, the co-creator of Night Vale. “In general I am both—as an artist and listener—kind of not interested in sound-effects heavy audio drama. I prefer things that use sound design occasionally and mostly are music.”

So, for Welcome to Night Vale, he knew he “needed a music bed.”

Joseph Fink knew Jon Bernstein (of the band Disparition) from the website Something Awful. “He had hours of music online that was perfect for Night Vale,” he told me, “so I asked him if I could just use it. And he said sure.”

Ever since then, “it’s been the same process—I have the entire library of Jon’s music that is available, and for any given section, I look through and pick a song I like, and place it against the text.”

For Alice Isn’t Dead, Jon Bernstein takes a different tack while composing the music, as the feel of the show is different. “In that one,” he says, “I score completely bespoke music for every episode. Every episode is unique.”

How he does this varies depending on the episode. “Sometimes, if I know what’s going to happen, I work on themes. Once I have the script and the recordings, I’ll sort of mold what I’ve started into the final shape.” However, sometimes he’ll wait until he can analyze an actor’s readings more closely so he can “play to that performance.”

In summary, different shows require different combinations of music and sound design—different ways of supporting the story. It’s best to consider this when moving forward with your sonic palette.

5. Keep pacing in mind

Like music, audio fiction podcasts have a flow—a tempo if you will, one you must preserve and convey as an engineer. If you’re coming from the music industry, you can use your innate feel for music as a way to inform your recording and mixing decisions.

Says Vincent, “Oftentimes as a musician I’ll know, okay, wait a second, this doesn’t feel urgent enough.” Vincent went on to say that during the editing process, the pace of the show is often poured over by various members of the team. When they leave him to the mix, he makes sure follow the guideline they’ve all created.

However, there’s another way to build a sense of pacing into your project.

“I come out of theater mainly,” says Joseph Fink, who likens pacing to a kindly game with the audience. “I think a lot about what am I trying to do with the audience, what journey am I trying to take them on, what am I trying to make the feel, and where is their energy at, at any given moment.”

6. Use EQ, stereo placement, and reverb for environment and creativity

EQ, ambience, and the stereo field are more than tools to create a static sonic picture. They can enhance the sense of place, the story, the feel, and many intangible aspects of the final product. Take how Vincent might use EQ:

“If something needs to sound like it’s coming from a wall, I’ll take away top-end.” Conversely, “if it needs to sound hyper real, maybe we’ll add some top-end and bring some of the mouth sounds up and make it really crispy.”

In conjunction with EQ, reverb helps to achieve a sense of space in a more cinematic manner than music-mixes might demand.

“If it’s a scene that has movement,” says Vincent, he’ll find himself “thinking about the movement, thinking about how that plays out in the stereo field, and the front-to-back of the mix.”

For creating the feeling of journeying from front-to-back, Vincent uses “level plus whatever reverb I’m using for the feel of that room or space. I try to think of the depth of field to be a combination of increased reflection and decreased level if it’s going back.” The opposite is true if a character is coming towards you: increased level and decreased room reflection.

As for stereo implementations, creative possibilities abound. Take the episode of Night Vale entitled “All Right.”

“It only played in your right ear,” Joseph Fink says. “It was designed so that you were supposed to listen to it with your left ear uncovered, and the story incorporated the sounds you were hearing wherever you were.”

This creative, stereophonic move ultimately served the story—and that, again, is the key.

7. Find a level and then stay there

This had been a personal concern of mine as someone who is obsessed with loudness standards. Of this topic, Vincent says he doesn’t “adhere to a standard entirely.” He acknowledged that conventional podcasts tend to hang around “-16 [LU], something like that. I keep it around there. I try not to go too much louder than that—it definitely does not need to be as loud as a record.”

Joseph Fink, on the other hand, has a different approach. “Generally, I compress the sh*t out of it. My goal is, it pretty much rides the red, because I’m mostly designing for how people listen to podcasts, which is on headphones or on car speakers.”

There isn’t a codified standard as of yet, but members of Night Vale Presents seem to care about consistency. You can see this in the “compress the sh*t out of it” approach (which yields vocal uniformity), and in the following nugget of wisdom:

“Once I’ve established a loudness,” says Vincent, “I’ll keep it going for that show. I’ll always match it to the one before. If it’s a ten-episode series, I’ll make sure that those ten episodes feel at home with one another in terms of loudness—unless there’s a reason for one, from a storytelling perspective, be louder or be softer.”

8. Reference, reference, reference!

As with all audio disciplines, referencing is key, and here Vincent has a specific tip:

“Listen to it in different places. You come to the material differently if you’re not always listening in your bedroom or in your studio on a pair of monitors. Take it in your headphones, go for a walk, get in the car with it. All that stuff helps. Don’t only listen to it in the studio. You should only mix it in the studio—try and keep that consistent—but try to consume it too. It’s not a good idea to only ever listen to it where you have immediate access to it.”

He also recommends that you check your mixes in earbuds of some kind. “I keep the earbuds right there when I’m mixing, and I check them. I don’t work on them, because I don’t like torturing myself, but I’ll check them.”

General Advice

We are rapidly running out of space for some of the more headier tips, so I will offer them up in quick succession.

9. Understand your collaborators and serve their needs

The size of the team doesn’t matter—when you collaborate, attune yourself to the people involved, be they writers, musicians, or actors.

Says Bernstein, “Outside of Night Vale, most of the people I work with are in theater. You get a wide range of people with different level of direction they give, so the main thing is listen. Listen to the person you’re working with and just kind of pick up emotionally on where they want to go, and try to feel what they’re feeling.”

10. Work on something you love, and forget about the market

When you’re starting out, you should “work on stuff that you really believe in,” says Vincent. “Make it really good. Go to town. Go the extra mile, one hundred percent. Even if you’re not really getting paid” as much as you think you should be.

Vincent acknowledges this can be problematic advice, but this course has worked out for him. “If I love something, even if there isn’t a great budget, I’ll find a way to make it work. I think that’s a good route—to work on artistically gratifying products, because if you love it, other people will probably love it, and that puts what you do out into the world.”

Joseph Fink summed it up in this way:

“Make something you like. Because if you try to chase the market, that doesn’t work, and the best case scenario is that it will become successful and you’ll be forced to make something you don’t like in order to make a living. So make something you like—and make it with people you like.”

11. Serve the story with all your decisions

We’re closing on this by-now old chestnut for our final tip, because it is the most important aspect of the work. You can see it in the way Joseph Fink chooses music, or the manner in which Bernstein composes to an actors take. Vincent summed it up like this:

“Be in love with the sound, be in love with the process of making good sound, but pay attention to the story. Don’t do superfluous things because they’re cool or they’re fun—you’ll have so many opportunities to do cool and fun things along the way.”