The history of mastering: evolution of techniques and technology

Audio mastering evolved in scope as technology entered the digital realm. In this article learn about the history of mastering, and its role in music production today.

The art of audio mastering can sometimes be described as a "dark art" (in my opinion, this description is overly dramatic), but perhaps this arises from the fact the history of mastering is a bit less understood in the grander scheme of music production.

Much of the history of recorded sound overlaps, and in the early days technology was pushed forward by research advancements for telephone and radio technologies. So today, let's dive into the history of mastering – and the history of recorded sound.

Interested in getting started mastering audio? Check out iZotope Ozone.

(A brief) history of recorded sound

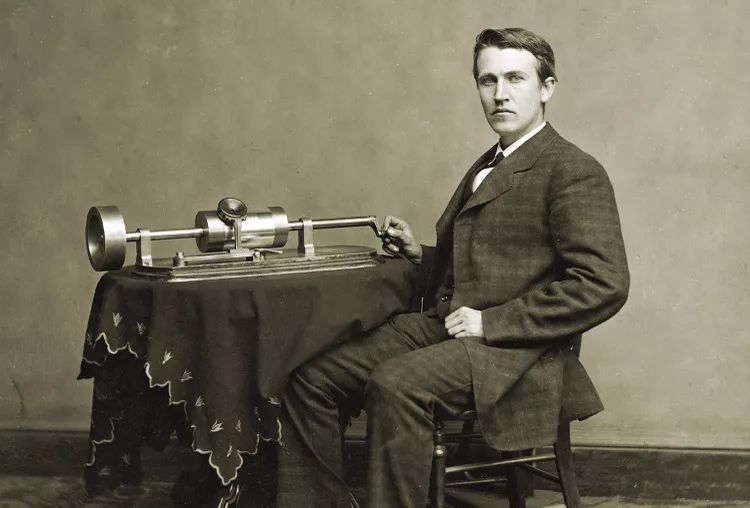

To understand how audio mastering got to where it is today, let’s briefly explore the history of recorded sound. The beginning of modern acoustic recording and the phonograph were invented in the late 1800s. The phonograph was invented by Thomas Edison in 1877, and allowed sound to be recorded through a large cone that focused the pressure of the sound waves through an etching device onto a wax cylinder. Although the fidelity was low compared to today’s standards, it was a remarkable feat at the time.

Thomas Edison and an early phonograph

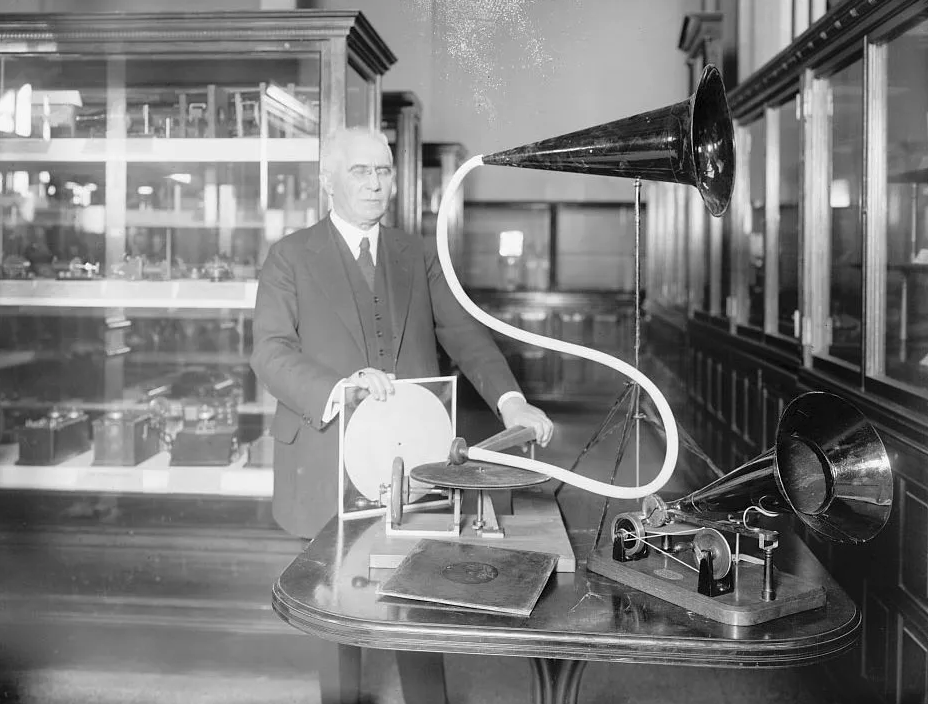

In the late 1800s Emil Berliner developed Gramophone discs made of shellac (these records were also called “78s,” named after the revolutions per minute by which the disc spun) that were more robust than cylinder recordings. These shellac records were the predominant consumer format until World War 2 (a wax disc of the recording was made, and electroplating created a metal stamper to press the shellac – not dissimilar to how vinyl records are made today!).

Emil Berliner with a gramophone

Technology evolved quickly in the first 20 years of the 1900s. Radio came into existence in the late 1800s, and with the invention of the vacuum tube amplifier by Lee De Forest in the early 1900s, louder and clearer signals could be sent over radio. Until 1925, all disc recordings were done “acoustically,” that is, without any electrical amplification, but by similar methods to the gramophone – mechanical amplification via a cone.

Western Electric (later Bell Labs), also spearheading vacuum tube amplification technology, and EC Wente, an engineer at Western Electric, patented the first condenser microphone in 1916. This ushered in the modern age of electrical recording – simply speaking, a transducer converting an acoustic signal to an electrical signal for the purposes of amplification, recording, or playback! In time, other companies such as Georg Neumann, RCA, etc. all contributed to the variety of microphones available…and the first dynamic mic was produced in the early 1930s.

The next real innovation in recording technology was magnetic tape. The Germans were researching magnetic tape during World War 2, but after the war was over, the United States (which had been doing research of its own) pushed forward with the first reel to reel machines via the Ampex company. Bing Crosby was one of the first major recording artists to push the new technology and invest in Ampex.

Harold Lindsay with the Model 200A in the lab

Up until this time, a recording usually had one engineer working through the whole process; recording, cutting the wax disc – microphone setup was relatively simple, and the band mostly balanced themselves. With the advent of these reel to reel machines, engineers were trained more specifically in the process of taking that tape and cutting it accurately to the acetate disc. In the late 1940s 33 RPM and 45 RPM records were developed (now made of the material we are familiar with, vinyl!) – which also made the process more involved with the different speeds.

This task was further reinforced by the RIAA (Record Industry Association of America) standardizing the EQ curve of playback devices. As the process became more specialized, these transfer engineers had a larger creative role in creating the lacquer masters used for the record making process.

Analog to digital, creative processing

Until the 1980s, while various playback formats came into being and were purchased by consumers, audio was consumed and recorded in the analog realm. In the late 1970s and early 80s, we started to see the makings of today’s modern Digital Audio Workstation (DAW).

The first digital recordings were pioneered in Japan in the late 1960s into the 1970s, but recording audio digitally didn’t ramp up in use until the 1980s, as the processes needed for these recordings became more advanced and mainstream.

Music production technology had been advancing steadily since the invention of the reel to reel machine. Multitrack recording, cassette tapes, digital delay, portable synthesizers, the list goes on. Soundstream (the company that made one of the first digital tape recorders in 1977) made what many consider to be the first digital audio workstation, the Digital Editing System. It consisted of a minicomputer, oscilloscope to display waveforms, and video display controls. Interface cards plugged into the system, allowing for integration with analog recorders as well as their digital tape recorders.

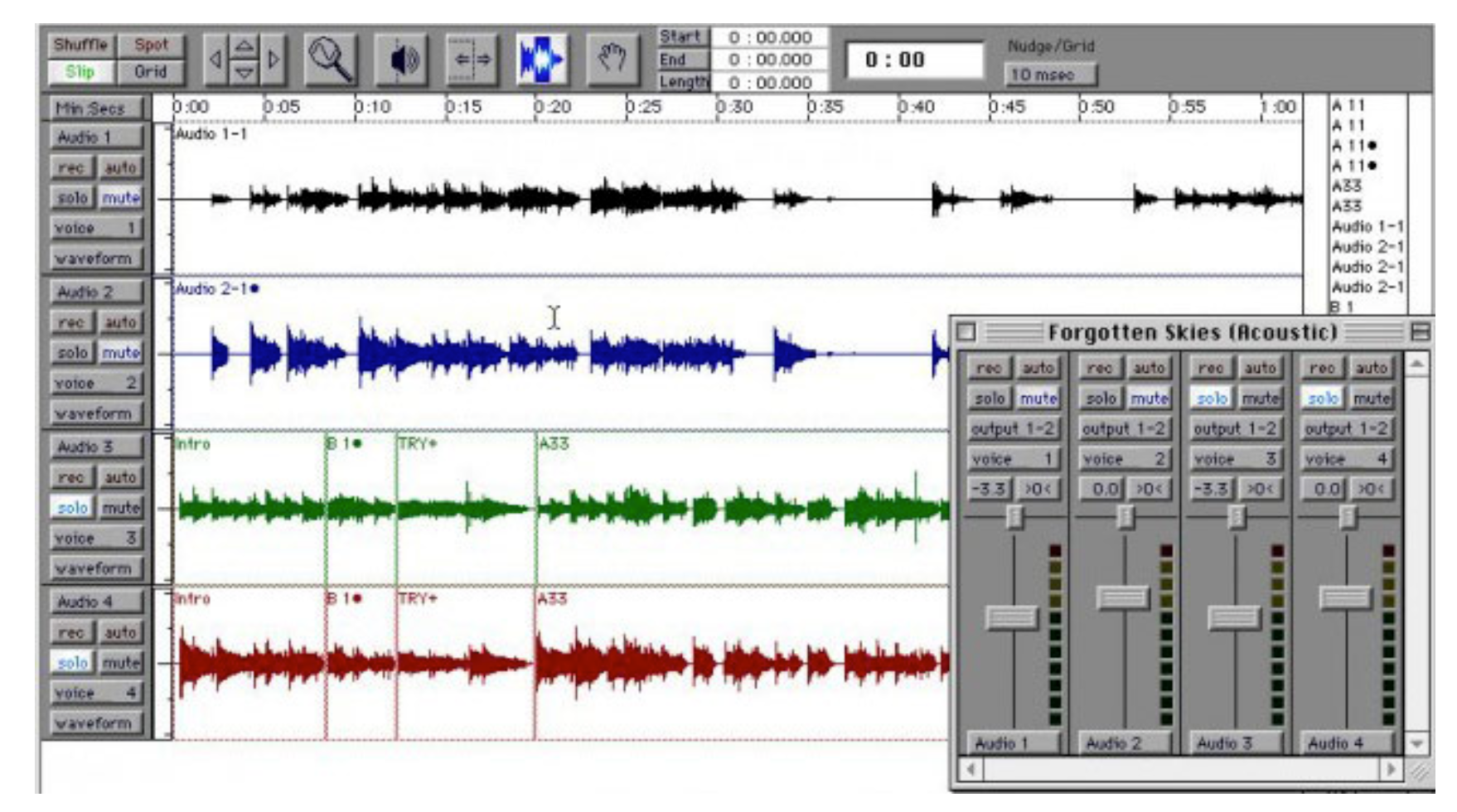

While only able to perform very simple edits, it was a revolutionary idea at the time. The invention of MIDI coincided with personal computers being able to perform more creative tasks via the introduction of more complex Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs). Some important early DAWs included Sound Designer/Sound Tools by Digidesign, and in 1989 Sonic Solutions introduced The Sonic System, the first non-linear digital audio editor (allowing audio to manipulate in any order, outside of a linear timeline, with non-destructive editing). As technology progressed, DAWs such as Cakewalk and Cubase developed, and ProTools as we know it was introduced in 1991. The list continues today.

Pro tools 1.1, circa 1991

As affordability, power, and features increased, DAWs allowed for creative possibilities that brought a new dimension of responsibility for mastering engineers. The advent of the CD in the early 1980s paralleled the transfer of tape to record. While not an analog process, the making of a DDP (Disc Description Protocol) that was used to burn CDs in a plant required a set of skills suited for the mastering engineer – always bridging the gap between the creative process and distribution process.

Not only did the role of the mastering engineer change, but the roles of everyone involved in the production process changed, evolved, and allowed for faster, easier ways of collaboration. Perhaps though, out of all the roles in the music production process, the mastering engineer’s gig went from more of a technical QC job, to one that requires as much nuance as a mix engineer, or tracking engineer.

Tools of today and beyond

So where are we now? As a mastering engineer, I am responsible for QC and final touches – occasionally that may be very simple level adjustments, and EQ changes. Other times, I may find myself adding reverb to a few songs on an album to help them sit in a space better. I may also spend a lot of time fixing extraneous noises in iZotope RX. I may apply mid/side processing techniques to allow for greater control of the stereo imaging.

In the present day, the tools we have available to us are very complex. With assisted audio technology and other AI driven processes, we are able to be creative in ways never thought possible. Through this advancement, audio can be analyzed and processed suggested on the fly, to ease the creative process, and to minimize the length of time spent on a project.

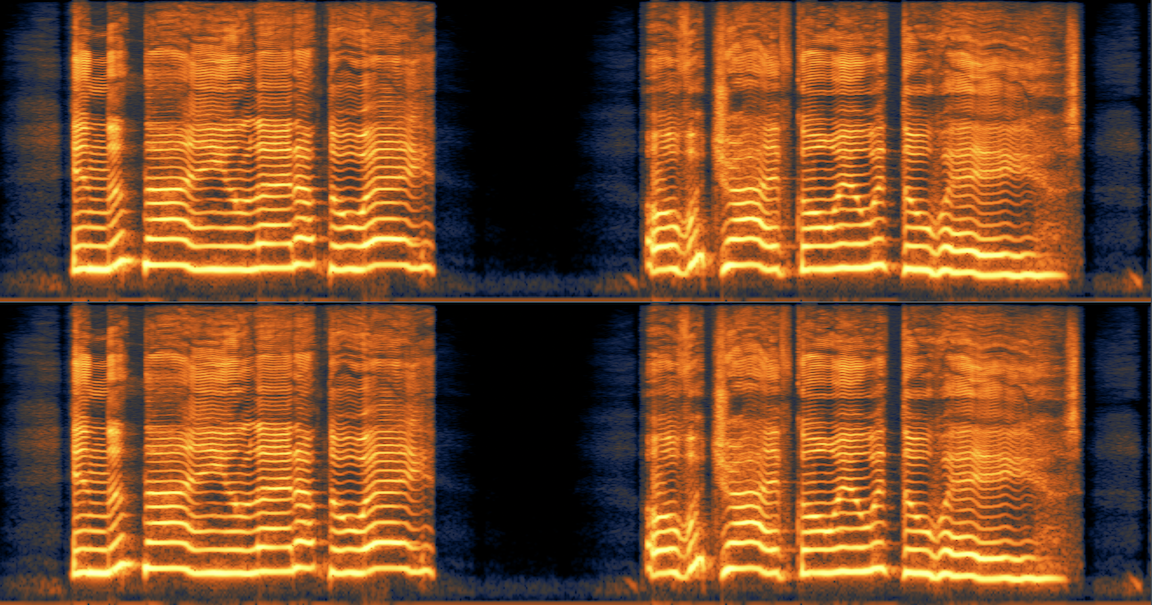

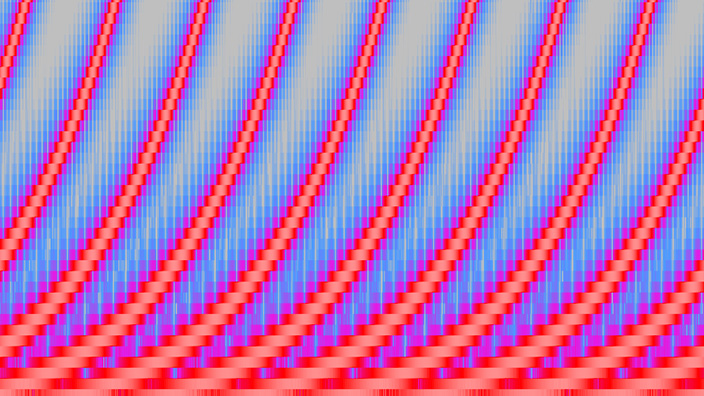

Ozone’s Master Assistant uses this intelligent technology to help find a good starting point when mastering a track. Play the loudest section of your mix, and the software will analyze, in broad strokes, different dimensions of the mix. From there, it will suggest settings for you to work from. This is where taste and creative vision come in – while it will help assist in the creative process, at the end of the day, it is you and your clients’ ears that makes the final choice.

Ozone Master Assistant analyzing audio

Suggestions after analysis

Mastering, from the beginning to today

Audio mastering evolved from being a tape transfer expert to being a format expert with a lot more opportunities for creativity. The tools we have access to today to be creative and shape sound have come a long way from the wax cylinders of the late 1800s. While the role of the mastering engineer may have evolved since the days of only transferring tape to vinyl, the principles of taste and intention remain the same.