Multiband Compressors vs. Dynamic EQs: Differences and Uses

Multiband compressors and dynamic EQs are some of the most useful tools available to audio engineers. In this article, we cover their differences and best uses.

Multiband compressors and dynamic EQs are some of the most useful tools available to mixing and mastering engineers. They allow for dynamic control of defined frequency ranges, providing some of the functionality and benefits of both EQs and compressors. Their ability to correct “problem” frequencies in a detailed and generally transparent way makes them extremely helpful for balancing a single sound or a full mix.

However, these two processors are often confused with one another, as they function on similar concepts and are used in similar scenarios. In this article, we'll cover the technical differences between dynamic EQs and multiband compressors, general uses for the two, and instances in which you should use one over the other.

But before we take a look at their differences and uses, let’s cover how each of these processors functions on a technical basis.

This article references a previous version of Neutron. Learn about

Neutron 5

Multiband compression

Digital multiband compressors are designed to function as their analog counterparts do. First, the full signal’s frequency content is split into several bands, usually three or four. These bands allow certain sections of the frequency spectrum to pass through, and on most plug-ins look like band-pass filters on an EQ.

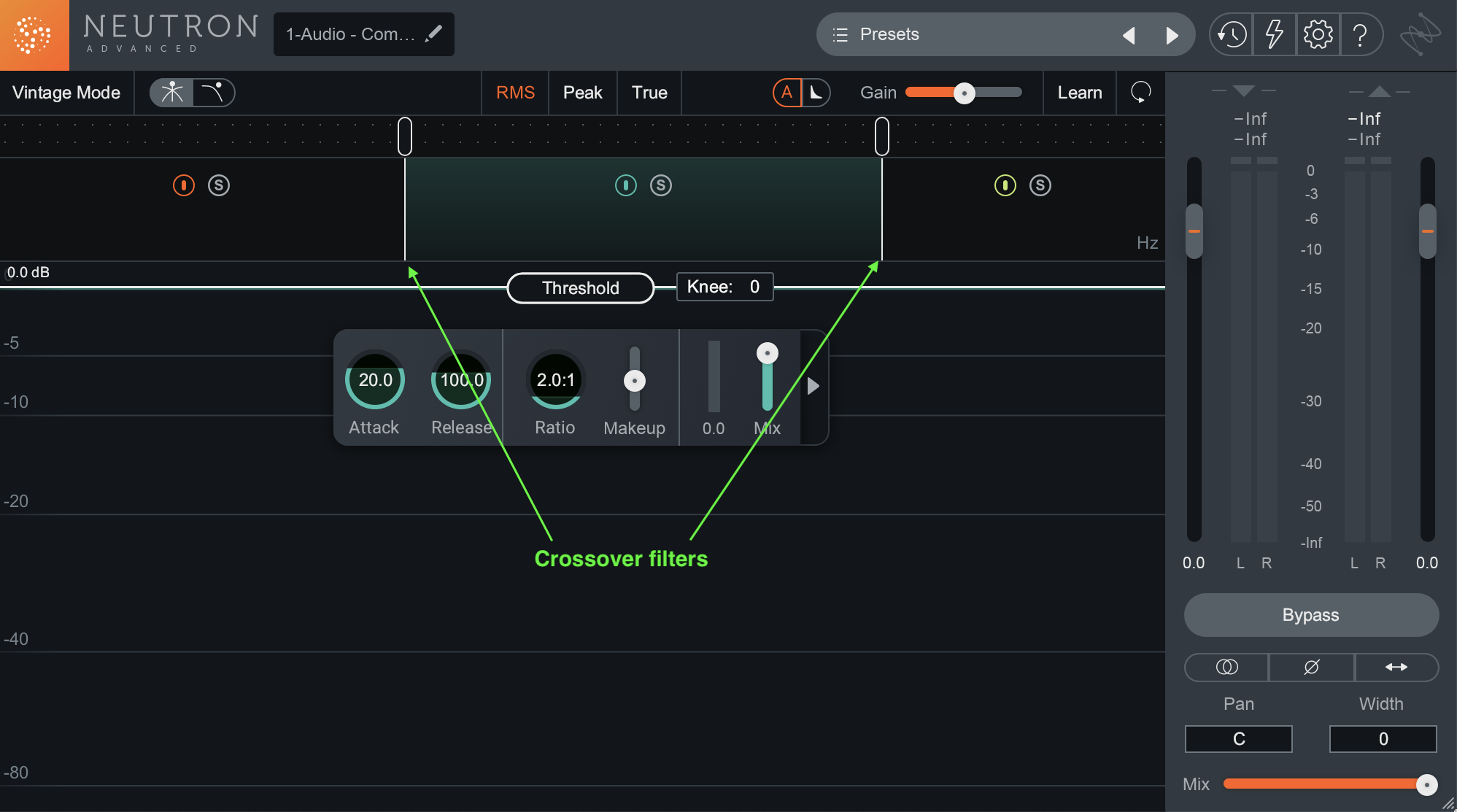

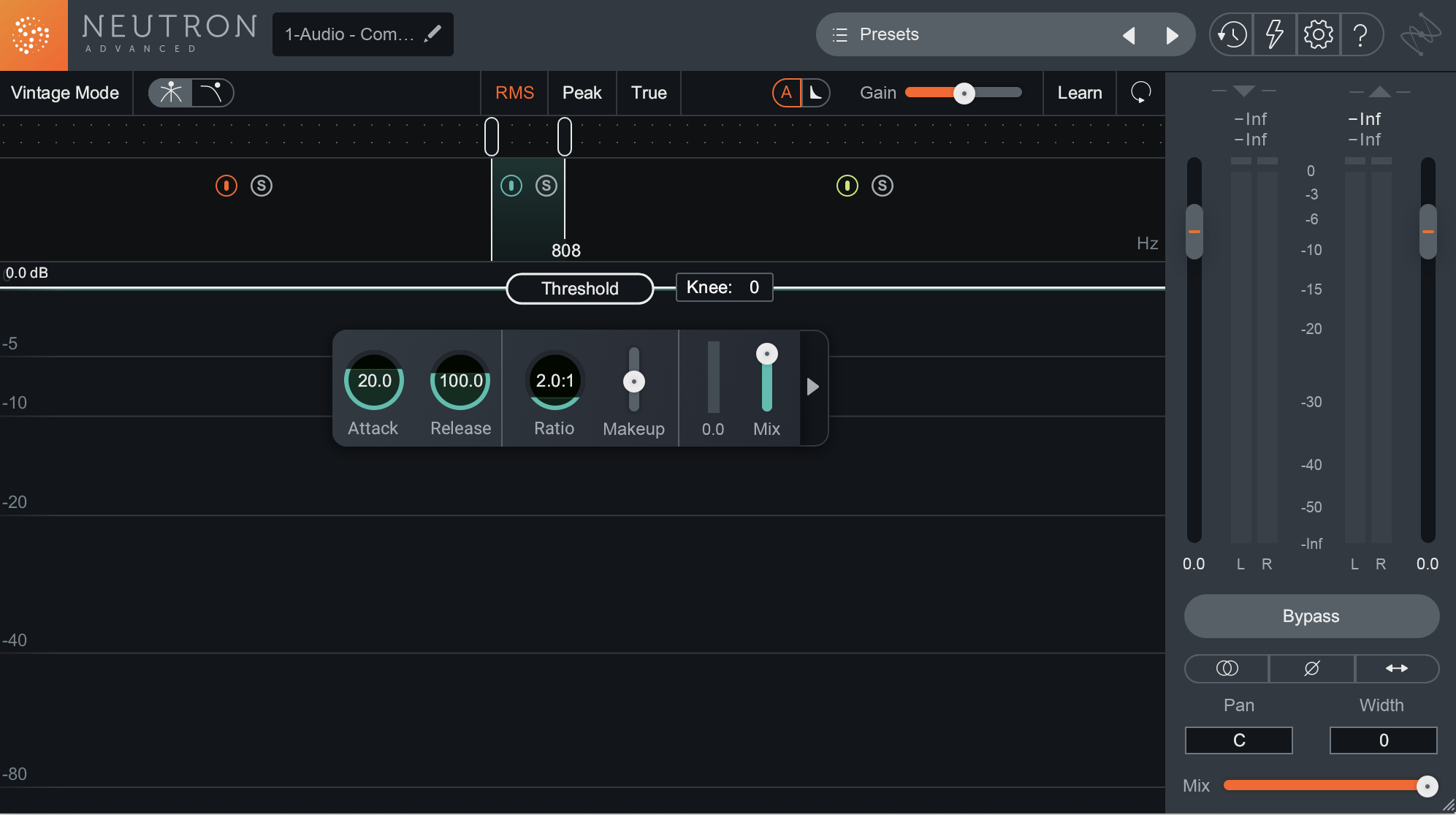

Below is a picture of the Compressor module in Neutron. Because you can add bands to separate the signal over the frequency spectrum, this compressor can essentially function as a multiband compressor.

Adding bands to the Neutron 3 Compressor module

Signal is split into these bands using a series of crossover filters, where the low-pass filter and high-pass filters of two adjacent band-pass filters intersect. The slopes, or pole numbers, of the LPF and HPF allow amplitude to remain constant over the crossover, meaning that the amplitude of signal near the crossover points will be largely unaffected.

Each band in the multiband compressor has its own dedicated compressor, and each of these compressors functions as you would expect: they have dedicated threshold, ratio, attack, release, and makeup gain parameters. Some multiband compressors, like this Compressor module, also have a knee parameter.

Adding bands to the Neutron 3 Compressor module

Signal within a band may cross the band’s threshold, causing its compressor to engage and signal within the band to be compressed. All bands will be then mixed together at the output.

Neutron 3 Compressor module multiband compression

Dynamic EQ

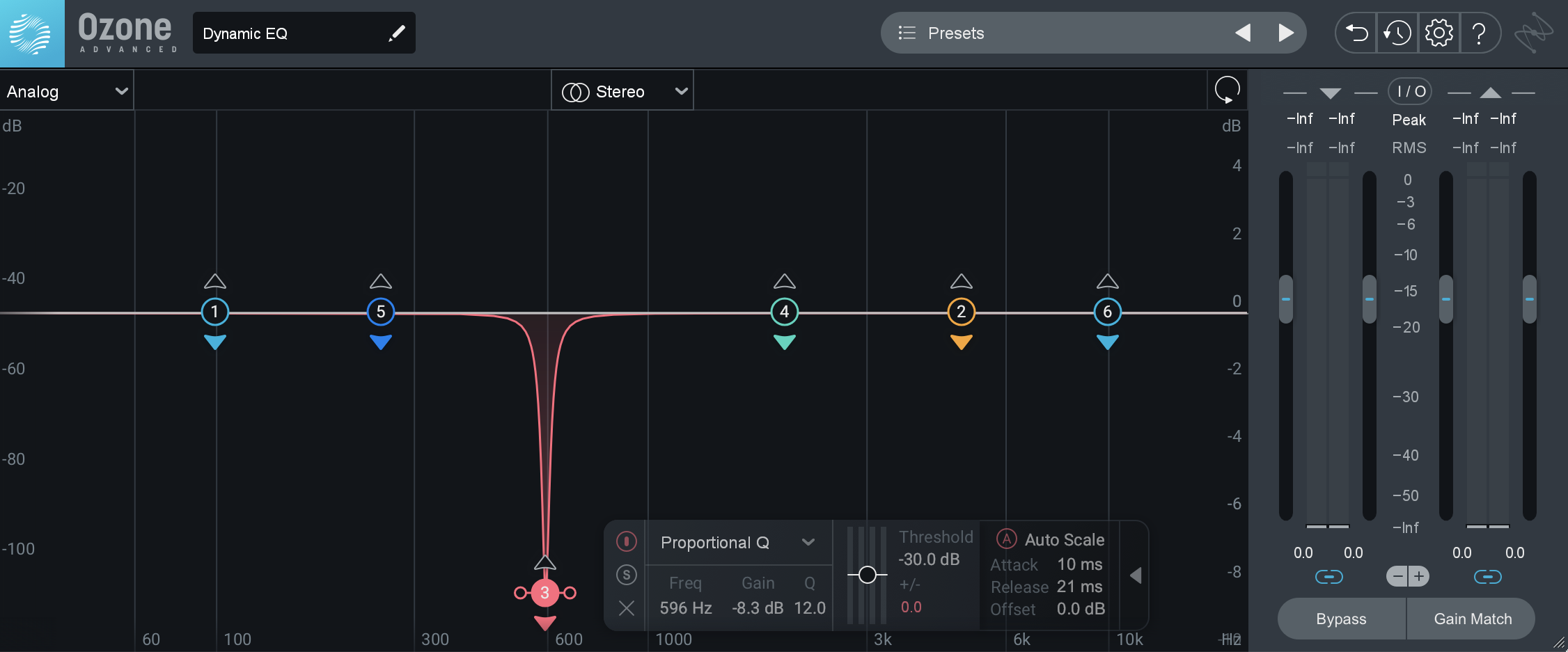

Dynamic EQ is quite similar to multiband compression, with many dynamic EQ plug-ins using common language found in compression. As you’ll see below on the Dynamic EQ module in

Ozone 12 Advanced

Ozone 9 Dynamic EQ “compression” parameters

However, you’ll notice several common EQ features as well. We have access to standard EQ bands and some classic EQ filter shapes: bell and shelf filters. Like they would on any equalizer, these EQ bands each have gain, cutoff frequency, and Q parameters

Ozone 9 Dynamic EQ “EQ” parameters

Unlike compression, dynamic EQ affects the sound by dynamically changing the gain of an EQ band. Like compression, however, and using the threshold, it does this proportionally in response to the amplitude of the input signal.

When signal crosses the threshold, the EQ band is either boosted or attenuated. The onset of this boost or attenuation is controlled by the attack time. When the signal’s level falls below the threshold, the EQ band returns to its default position based on the release time.

Differences

As you should be able to tell by now, dynamic EQs and multiband compressors are extremely similar, and it’s no wonder that they’re often used interchangeably.

The absolute simplest way to differentiate them is that a multiband compressor functions mostly like a compressor, but with some aspects of an EQ. A dynamic EQ functions mostly like an EQ, but with some aspects of a compressor.

Multiband compression functions like normal compression, but can act independently upon separate frequency ranges like an EQ. A dynamic EQ band functions like a standard EQ band, but processes signal non-linearly like a compressor.

However, as we’ve seen, there are a few technical differences that separate the two:

How the bands are split

The most notable difference between the two is due to the initial band splitting that occurs in a multiband compressor. This happens before any compression occurs. Even if the compressor is disengaged—meaning signal is not crossing the threshold—the frequency spectrum is split.

Though digital filters have become more transparent over the years, filters can naturally cause changes to the sound. Resonances, slight distortion, noise, or phase shifting can occur. The crossover filters found in a multiband compressor can cause these problems, even in a default state without any compression.

Multiband compression crossover filters

The phase shift that the crossover filters can cause introduces a small time delay, which in turn has the potential to cause comb filtering and phasing issues, decreasing the overall fidelity of the signal.

Some multiband compressors use “linear phase” filters, which address this phase shift problem. While a phase shift will still occur, it will be related to frequency in a literal manner. This causes a similar time delay, but doesn’t color the sound nearly as much.

Because a multiband compressor splits signal before any compression occurs, the signal is technically affected just by inserting a multiband compressor.

Dynamic EQs don’t split a signal into bands by default, and therefore don’t impact the signal until signal crosses a band’s threshold. EQ does work by introducing a phase shift, so this shift will occur when the dynamic EQ is working, but not until it’s engaged. Generally, this makes dynamic EQ a more transparent tool for controlling specific problem frequencies, as it has a lower chance of introducing artifacts.

Gain vs. ratio

Another difference between the two processors is that dynamic EQ functions using gain, or pure level, while multiband compression functions using ratio-driven compression. These two have different sounds, with gain movement being much more transparent than compression.

As a result, a multiband compressor can generally add a more pronounced sonic character to a sound, while a dynamic EQ will likely sound more surgical and sterile.

Number and width of bands available

The two processors also differ in the number and width of available bands. Most multiband compressors are capable of splitting signal into three or four frequency bands, each of which cover a relatively wide range of frequencies.

Dynamic EQs, on the other hand, tend to have more available bands—often four to six, sometimes as high as eight—or the capability to insert new bands. They can also be much narrower, allowing the user to control specific frequencies more easily than they could with a multiband compressor.

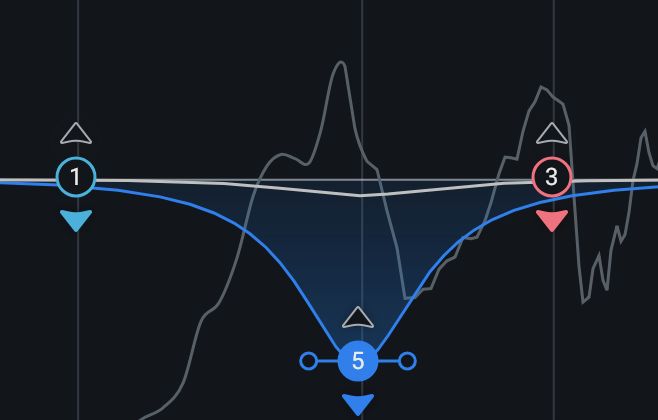

Narrowest dynamic EQ bands

Narrowest multiband compressor bands

Boosting vs. attenuating

Lastly, most—if not all—dynamic EQs have the ability to boost frequencies, while a standard multiband compressor cannot. Multiband expansion can have the same general effect that dynamic EQ boosting does, but not all multiband compressors have an expansion mode.

General usage

Though they have a few differences, dynamic EQs and multiband compressors generally have the same purpose. They’ll most often be used in place of a standard, static EQ to control and attenuate “problem” frequencies or frequency ranges, but only at certain times during a signal’s performance.

The dynamic nature of these two processors give them an advantage over a standard EQ. As they process signal only when the designated frequencies cross a threshold, frequencies will only be attenuated during parts of a track when they become too loud.

Unless you were to automate the gain and bypass—a pretty tedious process—a standard EQ will do this globally, always attenuating the set frequencies. This is a static and detached way to process a signal, and does not react to the music at all.

The dynamic attenuation of a dynamic EQ or multiband compressor also affects signal proportionally according to how far it crosses the threshold. This proportional attenuation would be quite difficult to replicate using static EQ automation, and allows dynamic EQ and multiband compression to sound connected to the sounds in your mix more musically.

In addition, static EQ attenuation can be an issue when applied to instruments that play a range of different notes. As a regular EQ band will not move with the notes, and in turn will be affecting different harmonics in each note, imbalances can occur between different notes’ frequency contents.

A dynamic EQ or multiband compressor can help to prevent these imbalances, as they will only react when a frequency becomes too loud.

Note: Nectar 3 also offers a solution to this issue with EQ Follow Mode.

Dynamic EQ and multiband compression can be used in any stage of the music production process, from sound design to mastering. As effect inserts, they’re especially useful when dealing with recordings of real instruments, as certain notes or parts of the performance may have distracting resonances. One of these two processors can be used to neaten things up.

Strictly in a mastering context, multiband compression can be hit-or-miss. On the positive side, its ability to assign separate attack and release times to each band allows for more intentional and specific compression. Attack times for the compression of lower frequencies can be increased—so low transients have time to develop—while higher frequencies can be controlled more precisely with shorter attack times.

Ideally, however, mastering references the mix quite closely, simply augmenting it rather than changing it. With the potential drop in fidelity that comes with multiband compression—which can happen even with linear phase crossover filters—it isn’t extremely common in mastering.

Dynamic EQs provide many of these functions without posing as much risk to the signal being mastered.

It’s worth mentioning that dynamic EQs and multiband compressors can be a bit CPU-hungry, so it’s not a great idea to just replace all of your EQs with these processors. Instead, use them when you specifically need them.

When to use one vs. the other

Ah, here we are: when should you use one or the other?

The main deciding factors are the range of frequencies that you want to affect, the strength/transparency of attenuation, and whether or not you want to add any sonic coloration.

If you want to attenuate a specific “problem” frequency or small range of frequencies, a dynamic EQ would be your best bet. The option to have narrower bands allows for this kind of focused attenuation.

A common use would be controlling a few resonant words in a vocal or other instrument. You can even de-ess a vocal with a dynamic EQ by placing the node at the performer's most sibilant frequency—likely between 4–7 kHz.

Conversely, if you’re trying to control larger areas of the frequency spectrum, a multiband compressor works well. This semi-global frequency control is most commonly used to subtly process submixes, or the overall track balance in mastering.

If you want to attenuate certain frequencies by a large amount, a dynamic EQ is usually a better call than a multiband compressor. Dynamic EQ is more transparent than compression, and a multiband compressor trying to aggressively compress a signal may be audible enough to become distracting in the mix. Strong attenuation will usually be less distracting with a dynamic EQ.

However, this “sound of compression” may be something that you’re looking for. The non-linear way a compressor attenuates signal can add character to a signal. If you don’t need the surgical control, but want some subtle sonic coloration, a multiband compressor can be a better choice than a dynamic EQ.

Conclusion

Whether you end up using a dynamic EQ or a multiband compressor in your next project, both provide advantages that make a mix engineer’s life much easier. These processors can be used to control frequencies in a way that is transparent and musical, and using them in the proper circumstances is way more time-efficient than writing in gain and EQ automation.

The balance that these processors can help achieve and the time saved can make both your mix and the production process a whole lot smoother.