Record of the Year: an analysis of the 2025 GRAMMY® nominees

Explore an in-depth analysis of the 2025 GRAMMY® Record of the Year nominees, uncovering trends in mastering, production, and what makes these songs stand out.

I’ve been having a fun year doing some data storytelling for iZotope. First we had our mastering trends in 2024 article which examined trends in loudness, width, tonal balance and more across a great many chart-topping songs. Then we had a piece on music discovery trends and where fans are finding new music.

Now, to wrap up the year – I know, it’s January, but this feels like a retrospective of 2024 in some ways – we thought it would be fun to examine the nominees for the Record of the Year GRAMMY and maybe even see where they fit in with our previously observed mastering trends. And of course, we’ll see what we can learn from them along the way.

Follow along with this tutorial using Tonal Balance Control, a plugin that helps you overcome your listening environment and achieve a balanced mix.

What is the “Record of the Year” in the GRAMMYs?

With so many awards available, it can sometimes be difficult to distinguish between some of the different – yet similar sounding – categories. For example, what’s the difference between Album of the Year, Record of the Year, and Song of the year? The key is understanding both which song(s) the award is for, and which individual(s) it’s meant to recognize.

For example, Record of the Year and Song of the Year are both for individual songs, however Song of the Year is specifically for the song writers. So, from the GRAMMY website itself:

“The Record Of The Year category awards a single track and recognizes the artist’s performance as well as the overall contributions of the producer(s), recording engineer(s), and/or mixer(s), and mastering engineer(s).” In short, it is an award for performance, production, and engineering of a single song.

An overview of the nominees

While the number of nominees in this category has varied between five and ten over the years, this year – as with last – we have eight nominees. While officially the genres span rock, country, dance, alternative, hip-hop, and pop, I’m going to let my bias show a bit and say that to me, they all feel more or less like pop – with the exception of Kendrick Lamar’s “Not Like Us.” Still, that’s not terribly surprising, and at least we have a little variation to our flavors of pop.

In the roster, we’ve got: The Beatles, Beyoncé, Sabrina Carpenter, Charli xcx, Billie Eilish, Kendrick Lamar, Chappell Roan, and Taylor Swift. And, while in my view the genre selection leaves a bit to be desired, we still see a decent amount of variety in both the tonal balance of the songs and things like integrated loudness, sample peak and true peak levels, and overall width of stereo imaging.

For example, here are the spectrums of all eight songs, averaged over their entire durations. Note that the x-axis extends up to 48 kHz since a few of the songs were at 96 kHz.

The nominees

So, with no further ado, here are the nominees for Record of the Year, along with some key credits and stats about the songs, and my own personal analysis and views of the performances, mixes, and masters.

1. The Beatles, “Now and Then”

Producers: Giles Martin & Paul McCartney | Mixing: Geoff Emerick, Steve Genewick, Jon Jacobs, Greg McAllister, Steve Orchard, Keith Smith, Mark 'Spike' Stent & Bruce Sugar | Mastering: Miles Showell

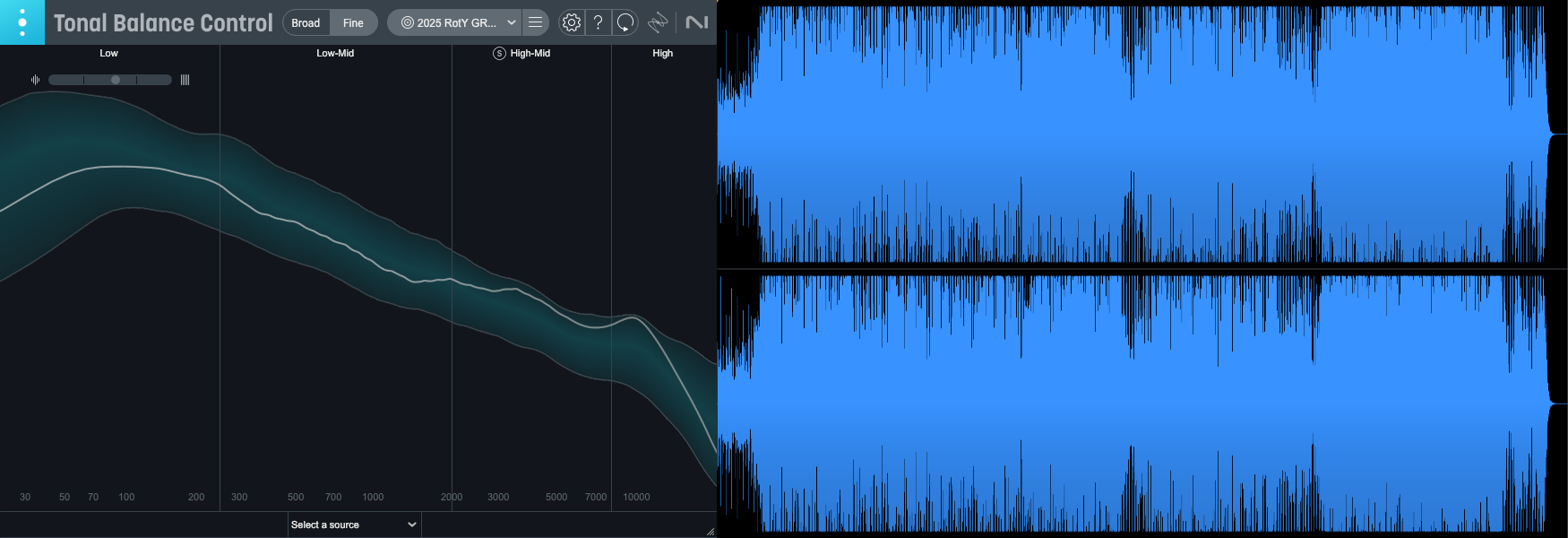

Tonal balance and waveform of “Now and Then”

True Peak: -0.60 dBTP | Sample Peak: -0.61 dBFS | Int. Loudness: -6.7 LUFS | Loudness Range: 4.6 LU

First in our list is “Now and Then” by The Beatles, and I have to say, technically, it’s a bit of an odd one. Now, who am I to criticize The Beatles or anyone in the star-studded list of technical personnel on this record? No one, that’s who, but you’re here for my opinion, so here we go.

First of all, while the file is at 96k, the frequency content is that of a 48k file. Some mastering engineers prefer the way their converters and hardware sound at 96k, and maybe Miles Showell is one of those guys, but it strikes me as a little out of the ordinary, especially when we consider the following. The maximum sample and True Peak values are both about -0.6, but those values occur just a handful of times. If we look at a histogram of the peak levels – which shows us how frequently a value appears – it looks much more like the peaks are limited to about -1.7 dBFS, something we can kind of see in the waveform above. Not only that, but this is the loudest of all the nominees, at -6.7 LUFS integrated.

So what gives? What I suspect – and I could be wrong – is that the mix was turned in at 48k and -5 LUFS, and Miles resampled it to 96k and turned it down a bit to allow for the additional peaks that are typically produced during resampling. But enough about the numbers! How does it sound?

You can tell it’s The Beatles, but it doesn’t sound the same as their previous releases. I’m not saying it needs to sound like The White Album, but even the 2019 remix of “Abbey Road” feels a bit more lively. The interesting thing here is that the Atmos mix of “Now and Then” offers us a very different perspective, and one I think is worth checking out. I’ll leave that to you to investigate!

2. Beyoncé, “TEXAS HOLD 'EM”

Producers: Beyoncé, Nate Ferraro, Killah B & Raphael Saadiq | Mixing: Hotae Alexander Jang, Alex Nibley & Stuart White | Mastering: Colin Leonard

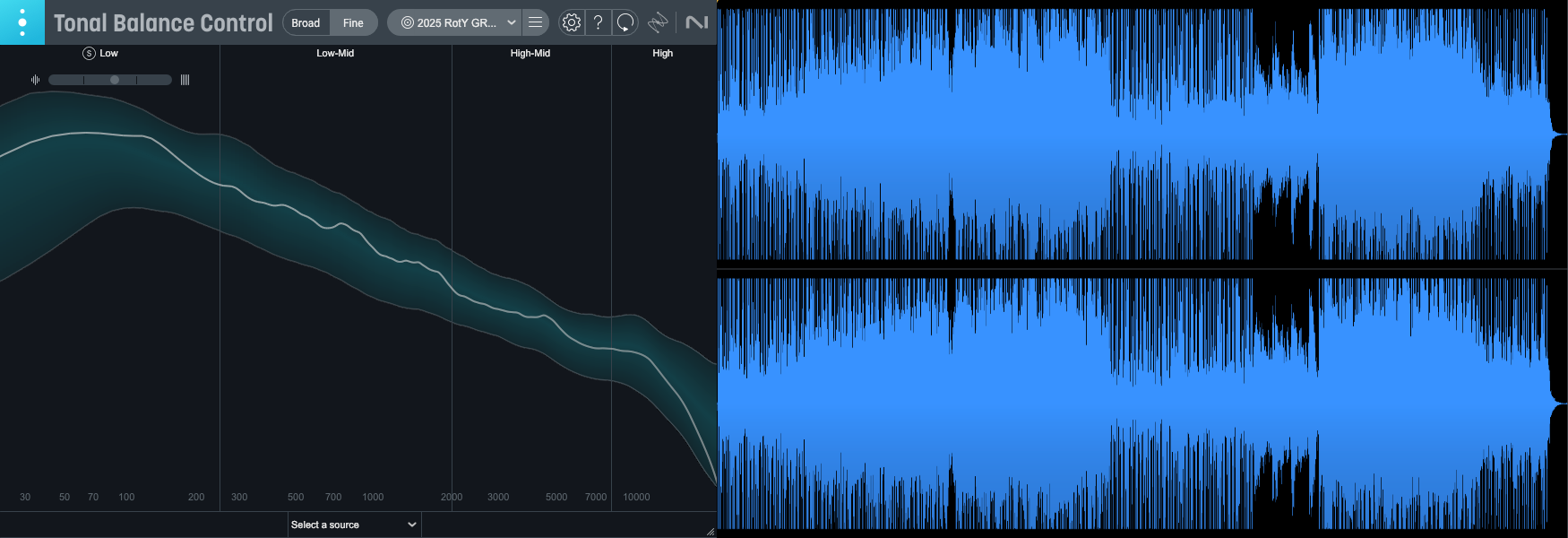

Tonal balance and waveform of “TEXAS HOLD ‘EM”

True Peak: +0.84 dBTP | Sample Peak: -0.01 dBFS | Int. Loudness: -7.9 LUFS | Loudness Range: 5.3 LU

With sample peak values right up to within 0.01 dB of full scale, this master sure makes use of all the headroom available. There are good qualities one can laud this record and album for – the songwriting, performance, stepping outside typical genre boundaries, etc.

The mix has some interesting characteristics. Notably, the kick has a looser, softer sound not typically found in pop, country, or R&B, particularly when the full arrangement comes in around 0:41. There are also elements of distortion throughout the mix that add excitement but also could distract the listener – I will leave that up to your ears to decide.

Out of all of the nominees, this one ranked lower on my personal scorecard.

3. Sabrina Carpenter, “Espresso”

Producer: Julian Bunetta | Mixing: Julian Bunetta & Jeff Gunnell | Mastering: Nathan Dantzler

Tonal balance and waveform of “Espresso”

True Peak: -0.37 dBTP | Sample Peak: -0.4 dBFS | Int. Loudness: -7.5 LUFS | Loudness Range: 2.9 LU

If you’re going to try to get a record up to about -7.5 LUFS integrated, this feels more like the right way to do it for me. There’s still a little headroom to give our playback DACs a bit of breathing room and the team has managed to retain some decent definition despite the very controlled transients.

The vocals in verse one from about 0:28 – 0:47 have some additional pumping and chattering that feels a bit unnatural. Maybe it’s the super-airy vocal pumping in response to the limiter without any wide BGVs to help mask it (as in later verses), or maybe it’s just something in the vocal production. Either way, a different processing and arrangement decision could have really put this over the top for me.

4. Charli xcx, “360”

Producer: Cirkut & A. G. Cook | Mixing: Cirkut & Manny Marroquin | Mastering: Idania Valencia

Tonal balance and waveform of “360”

True Peak: +1.99 dBTP | Sample Peak: -0.1 dBFS | Int. Loudness: -7.7 LUFS | Loudness Range: 2.4 LU

If you’re after an example of “true peaks are just free level,” look no further. With TP levels nearly a full 2 dB above full scale, it can be instructive to throw on a True Peak limiter like the Ozone 11 Maximizer, set only to engage above -0.09 dBFS, and listen to the difference. For me there’s a definite tonality change that I have to believe is attributable to the distortion products resulting from True Peaks over 0. Is it the same tonality change that you would experience on your interface/DAC? Maybe. Maybe not.

That’s the thing about True Peaks – how they sound depends a lot on what they’re being played through. And sure, you could say that’s the case with just about anything, but with True Peaks I find that difference gets exacerbated.

5. Billie Eilish, “BIRDS OF A FEATHER”

Producer: FINNEAS & Billie Eilish | Mixing: Thom Beemer, Jon Castelli, Billie Eilish, Aron Forbes, Brad Lauchert, FINNEAS & Chaz Sexton | Mastering: Dale Becker

Tonal balance and waveform of “BIRDS OF A FEATHER”

True Peak: -0.36 dBTP | Sample Peak: -0.57 dBFS | Int. Loudness: -9.3 LUFS | Loudness Range: 4.7 LU

Personally, I find a lot more to like here. Sure, there’s some grit and saturation – bordering on distortion, for example at 2:30.4 – but by and large it feels much more like a well-integrated artistic choice that adds to the aesthetic as opposed to a technical byproduct that detracts from it.

As with “Espresso” we’ve got some true peak headroom that will likely help keep tonality more predictable across playback devices, and with an integrated level of -9.3 LUFS, there’s room for the drums to punch above the average level and for the loud bits to get loud without too much distortion. Unlike “Espresso,” the vocal seems to be much more carefully treated here, with perhaps some very minor exceptions in the final chorus.

6. Kendrick Lamar, “Not Like Us”

Producer: Sean Momberger, Mustard & Sounwave | Mixing: Ray Charles Brown Jr. & Johnathan Turner | Mastering: Nicolas de Porcel

Tonal balance and waveform of “Not Like Us”

True Peak: -0.21 dBTP | Sample Peak: -0.25 dBFS | Int. Loudness: -9.3 LUFS | Loudness Range: 2.8 LU

And now for something completely different! There are two things I want to talk about here: massive low-end and intentional distortion in the sound design stage.

First, the fundamental of the main 808/bass is down at about 31 Hz and relative to the rest of the spectrum it is HOT – check the gif at the top of the article. I’ve seen people advocate for regularly using a high-pass at 35 or 40 Hz, and this is a great example of why we always need to use our ear and treat things on a case-by-case basis. This also leans into a trend I’ve seen in recent years of bigger and lower bass and I am here for it.

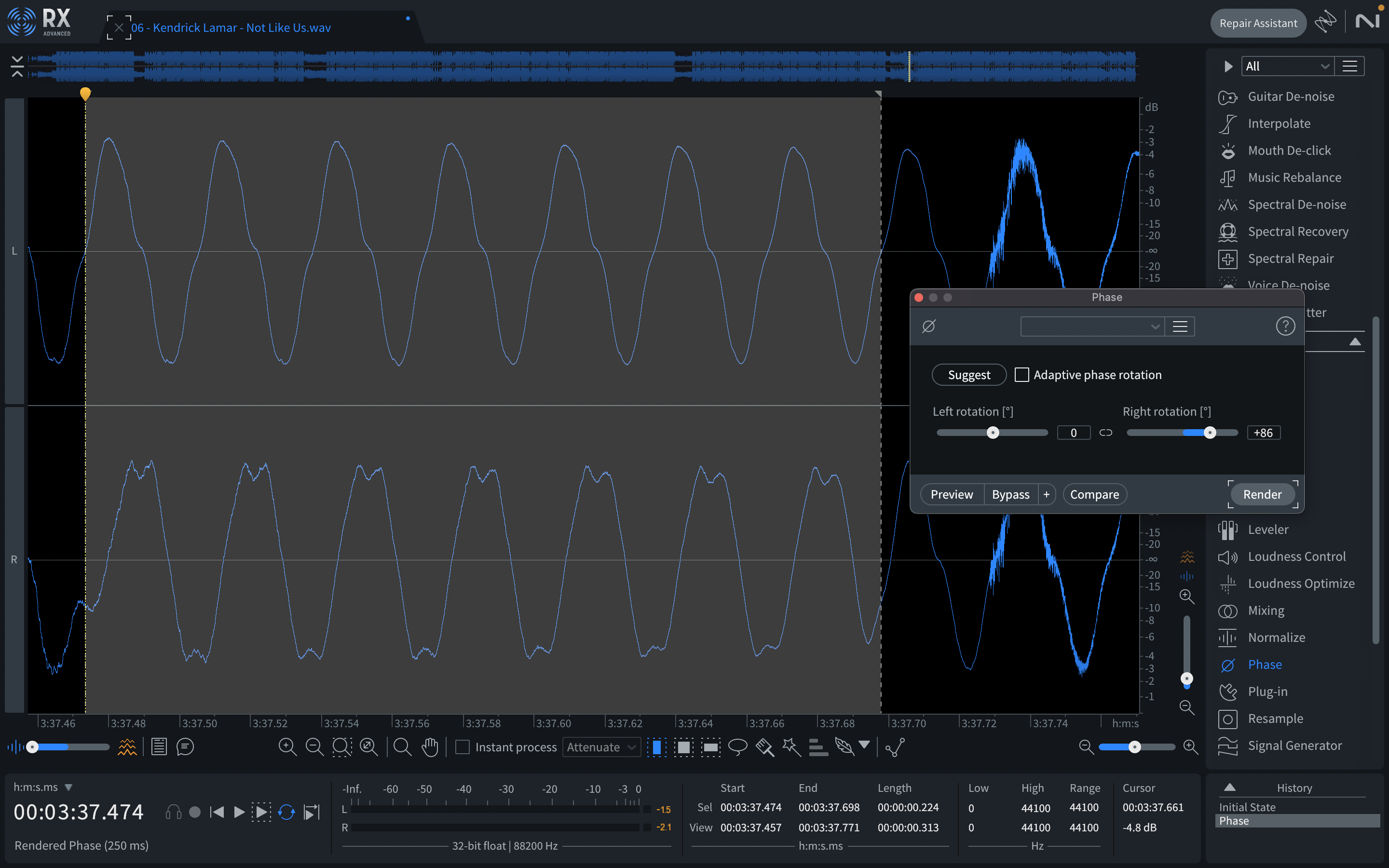

Second, there’s some pretty blatant distortion on the bass, but we can also say with a high degree of certainty that it was done on the bass channel in the mix – or earlier. How can we know that?

Bass distortion in “Not Like Us”

In the above image, I’ve found a section where there’s a relatively isolated bass note. In the left channel – on top – we can see how the waveform appears in the master. In the right channel – on the bottom – I’ve performed an 86 deg. phase rotation which yields a waveform much closer to what we would expect for some saturation with lots of early, odd-order harmonics when applied to that 808/bass. The takeaway? The saturation or distortion must have been applied fairly early on and followed later by EQ or something else that added phase-shift.

Here, then, is a case where the engineering really seems to be in service of the performance and production. Huzzah!

7. Chappell Roan, “Good Luck, Babe!”

Producer: Dan Nigro | Mixing: Mitch McCarthy & Dan Nigro | Mastering: Randy Merrill

Tonal balance and waveform of “Good Luck, Babe!”

True Peak: +0.26 dBTP | Sample Peak: -0.29 dBFS | Int. Loudness: -8.6 LUFS | Loudness Range: 6.5 LU

Now here’s a record I can get behind for Record of the Year! I find this to be a compelling performance that sounds great. The tonal balance is full and satisfying – I might be tempted to give it a couple little bumps at 280 and 5k Hz, but that’s a personal thing; the dynamics are controlled yet punchy and retain definition even during their loudest moments around 2:54; despite the use of clipping there’s no particularly obvious or unpleasant distortion.

If you’re after a modern pop sound, this is something to aspire to in my book, and frankly, out of the nominees here, it gets my vote for Record of the Year.

8. Taylor Swift, “Fortnight (feat. Post Malone)”

Producer: Jack Antonoff, Louis Bell & Taylor Swift, producers | Mixing: Louis Bell, Bryce Bordone, Serban Ghenea, Sean Hutchinson, Oli Jacobs, Michael Riddleberger & Laura Sisk | Mastering: Randy Merrill

Tonal balance and waveform of “Forthnight”

True Peak: +0.77 dBTP | Sample Peak: -0.3 dBFS | Int. Loudness: -10.2 LUFS | Loudness Range: 5.4 LU

This is a great record too. In some ways – mainly the tonal balance and slow, consistent build – I find it more satisfying than “Good Luck, Babe!” But, at the same time, the drums feel less satisfying and yet despite that, there’s a little more breakup and artifacting around them during the loudest moments – at 3:01 for example.

So again, if you’re after a modern pop sound, you could do a lot worse than to compare favorably to “Fortnight.” There are just those few little things that edge out “Good Luck, Babe!” over it for me.

A brief meta-analysis

Before we wrap up, I think it’s interesting to compare how these records stack up against the trends we observed earlier in the year.

| 2024 Trends | 2025 RotY Noms | |

| Avg LUFS, Int | -8.3, ±1 | -8.4 |

| Max LUFS, Int | -6.0 | -6.7 |

| Min LUFS, Int | -11.1 | -10.3 |

| Avg LRA | 5.5, ±1.5 | 4.3 |

| Max LRA | 10.8 | 6.5 |

| Min LRA | 1.4 | 2.4 |

| Avg M/S Ratio | 8.5, ±2.5 | 8.15 |

| Max M/S Ratio | 19.2 | 11.9 |

| Min M/S Ratio | 2.8 | 3.9 |

And sure enough, while the ranges – or maxima and minima – are smaller, the averages are surprisingly close. To me, that indicates that the trends we observed earlier indeed hold up when applied to a much smaller subset of music that could be considered the best of the best.

What can we learn from the Record of the Year nominees?

Sometimes learning what not to do, or what to avoid are as important as learning what to do, and thankfully I think these nominees give us both in nearly equal measure.

From these nominees, we can draw lessons that span both technical excellence and artistic vision. The Beatles' "Now and Then" and Beyoncé's "TEXAS HOLD 'EM" remind us that technical decisions can change the signature sound of an artist or genre, while Sabrina Carpenter's "Espresso" and Charli xcx's "360" demonstrate the delicate balance of achieving commercial loudness while managing true peaks, distortion, and other artifacts that can creep forward when level is pushed higher.

Billie Eilish's "BIRDS OF A FEATHER" shows how intentional saturation can enhance rather than compromise a recording, and Kendrick Lamar's "Not Like Us" proves why we should sometimes challenge conventional engineering wisdom. Both Chappell Roan's "Good Luck, Babe!" and Taylor Swift's "Fortnight" exemplify how attention to detail in the final stages can make or break a record, with Roan's track particularly standing out for its marriage of technical precision and artistic expression.

In the end, what makes these recordings worthy of GRAMMY consideration isn't just their commercial success or cultural impact, but how their technical execution either elevates or occasionally hinders their artistic vision. The best among them demonstrate that while modern production techniques and loudness standards have their place, they should never come at the expense of musical dynamics, clarity, and overall sonic integrity.

To achieve a balanced mix, try Tonal Balance Control for free.