What is metering in mixing and mastering?

What is metering in the mixing and mastering process? We examine metering tools as they relate to levels, frequency content, stereo spread, and dynamic range.

In the twin practices of mixing and mastering, we often speak of the meters, particularly after making bold decisions. "How does that look on the meters?" I might say to myself, often after midnight, when I’ve been mixing so long that my head feels squashed—never mind the mix.

Such talk leads us to our question: what is metering in the mixing and mastering process?

In this article, we’ll learn more about what metering is and what type of meters to use when mixing or mastering to help you get your desired sound.

Explore metering tools like

Insight 2

What is metering in mixing and mastering?

In mixing and mastering, metering is any useful visual aid that shows us where we stand. When used with our ears as a sort of check, meters can help us make better decisions, particularly regarding levels, frequency content, stereo spread, and dynamic range.

With this established, let’s get into a brief overview of the meters we use.

Level meters

Level meters are arguably the most prevalent meters we come across. They’re found in DAWs, outboard gear, and physical mixing boards. They show us a signal’s strength; put simply, they display how “loud” a signal happens to be at any given moment.

“Loud” here is in quotes because it’s not the most accurate term; it is, however, the most relatable/simplistic one.

Also, how “any given moment” is presented to us—how this “moment” is quantified and measured—can be quite confusing to unpack.

By definition, VU meters (implemented long before the digital epoch), tend to take longer to read the level of a signal (around 300 milliseconds). Conversely, they take longer to register when a signal has dropped to a lower value (again, usually around 300 milliseconds). This makes them credible tools for taking the average temperature of a signal, be it a mix or a single element like a vocal or a bass.

You might not have a conventional VU meter, like the one pictured below, in your DAW, though you’ll see them still on many outboard compressors.

Example of a VU meter plug-in in a DAW

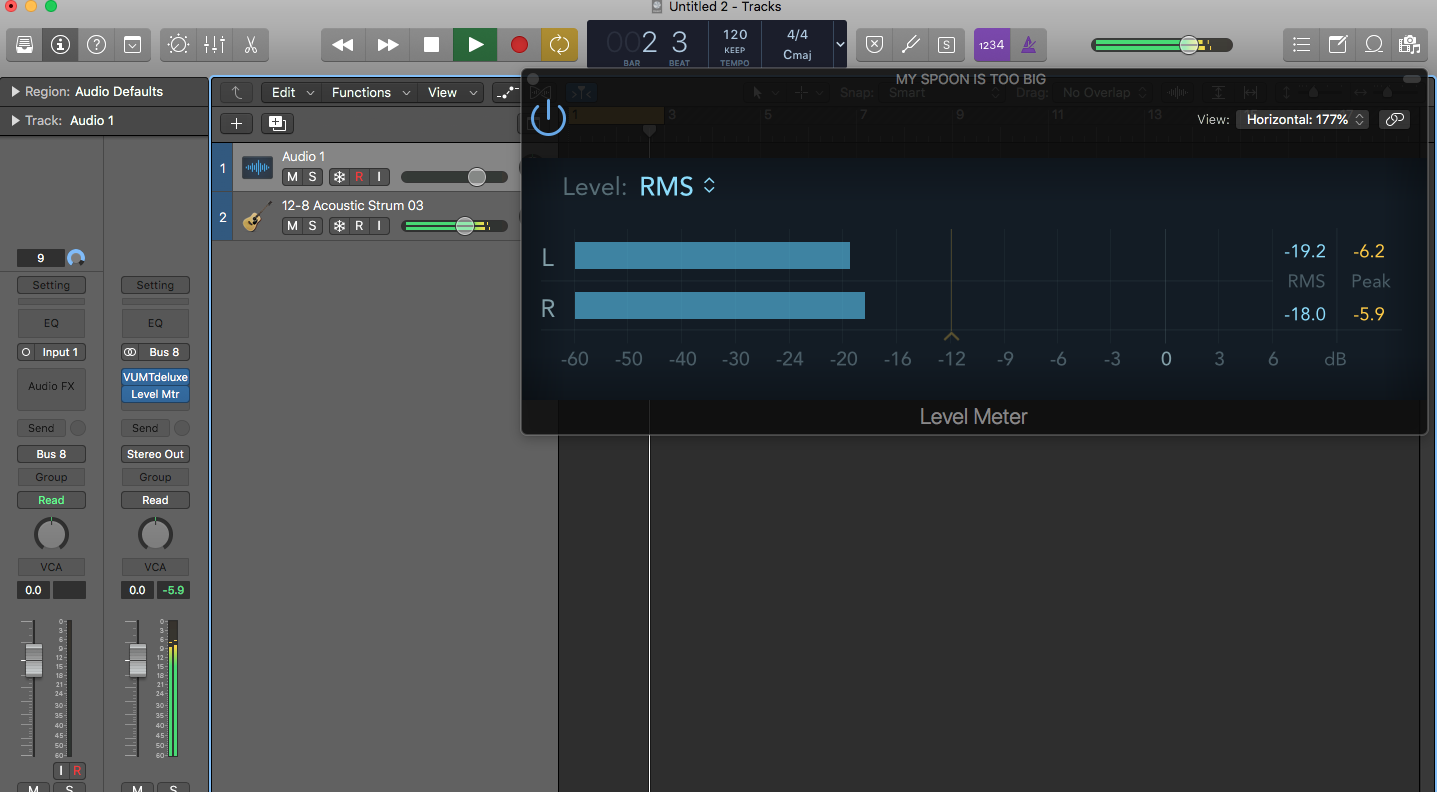

Your DAW’s RMS meter serves a roughly similar function, as it aims to portray the average strength of a signal, rather than its moment-to-moment peak value.

Example of an RMS meter in a DAW

But these kinds of meters aren’t as helpful for seeing, measuring, or quantifying the momentary transient, which is necessary for making sure you don’t overwhelm your mix/master, or hit your digital ceiling.

In these cases, engineers used to use PPM meters. We have now largely migrated to loudness metering for averages and true-peak metering for catching the quickest hits.

Loudness metering

Loudness metering is my preferred method of level metering because it is so versatile. A LUFS loudness meter always gives you three different readouts—momentary, short term, and integrated—and they’re all incredibly useful.

If you’re mixing a podcast or a dialogue scene for a film, momentary readouts help you judge the consistency of the voices, helping you make decisions to juice the gain so you don’t lose a word at the end of a sentence. Integrated loudness helps you judge the overall loudness of programmatic material—of a song, a film, an episode, etc—which is great for meeting standards defined by a company. For instance, Voyage Media has asked me to deliver podcasts that come in around 16 LUFS integrated, and so I use integrated metering to help me deliver that spec.

True peak metering

Short term loudness, on the other hand, is quite helpful for judging the overall level of a mix or master, especially in reference to other mixes/masters. I’d say it gets the most usage around here.

For short term loudness you’ll want to use the true peak metering. It tells you about nasty distortions that can be created in the digital to analog conversion process if your signal is running too close to the digital ceiling of 0 dBFS (a good explanation of true peaks and why they matter can be found here).

Loudness meters frequently give you a “loudness range” measurement to show you the difference between your quietest and loudest points. This tool is great for getting a feel for your overall dynamic range. In Insight Pro, pictured below, it’s labeled as “LRA.”

A metering suite like

Insight Pro

Frequency meters

As we have meters to help us judge level, we also have meters (visualizations) to help us judge frequency content. The most common one is the spectrum analyzer, which shows us, on a two-dimensional plane, the frequency makeup of our mix.

iZotope Insight Pro frequency analyzer plug-in

At the left of a spectrum analyzer sits our bass content, and at the right sits our high-end. From left to right, we see the specific order of lows to highs. That’s our X-axis; our Y-axis (the vertical plane), shows us the amplitude of these frequencies, in both positive and negative values.

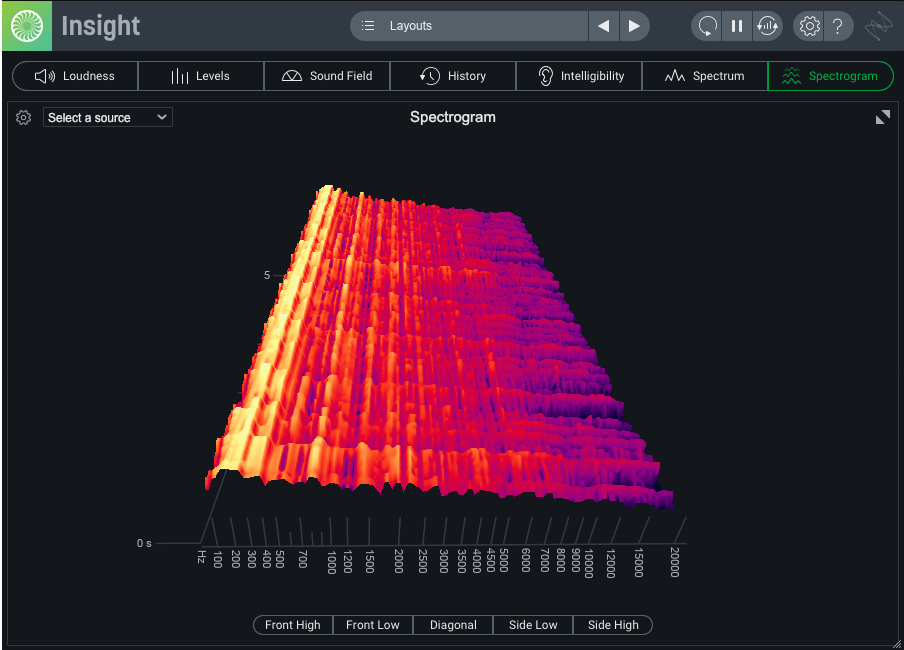

If you want to add a third axis into the view—if you want to see the amplitude of your frequencies over time—open the Spectrogram view of Insight Pro, pictured here:

iZotope Insight Pro Spectrogram metering plug-in

Now, we can see the frequency range over time.

We use these meters to help us achieve tonal balance, but it’s important to note that balance doesn’t equal a flat, zeroed-out response on the spectrogram.

There is, depending on the music we’re addressing, a slope to the sound we’re looking for, with greater values in the lows than the highs. Here, iZotope’s

Tonal Balance Control 2

Phase correlation meters

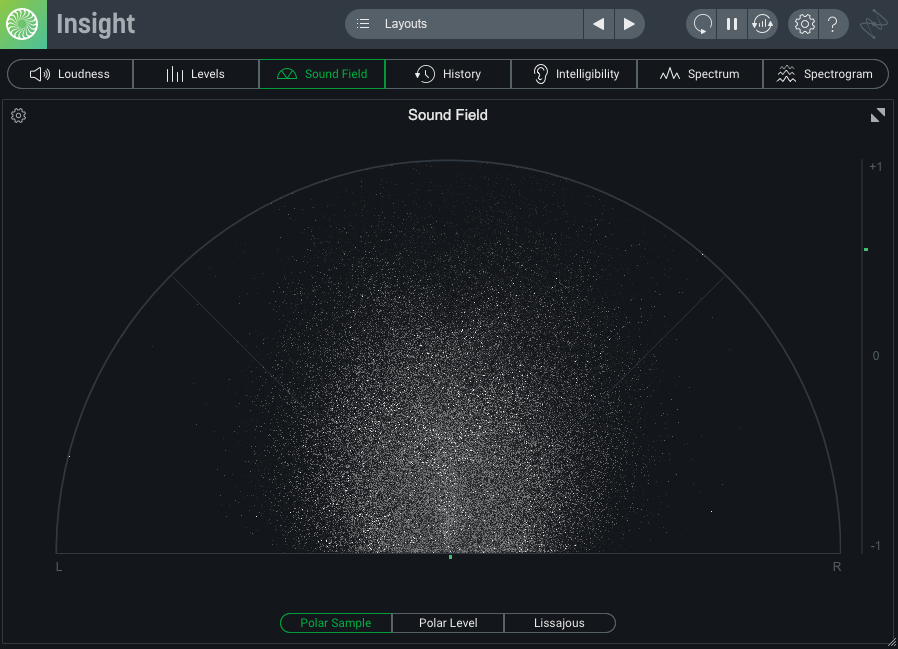

We often come across polarity, phase, and stereo meters in our practice. These measure two signals simultaneously to determine whether they are in phase with each other. Some offer pictorial representations of what the stereo-plot looks like as well. However the meter looks, it is essential for making sure we’re fashioning a product that can translate to all systems, from the highest of the hi-fi to the lowliest mono iPhone speaker.

Pictorial meters, such as the ones present in Insight Pro’s Sound Field tab, give us excellent visual aids and representation of phase correlation.

iZotope Insight Pro sound field metering plug-in

The phase correlation meter is the read out on the vertical right, spanning from -1 to plus 1. It displays a value of +1 when it judges two signals as being completely correlated with each other (as in, they’re the exactly the same, giving you a mono sound), and -1 when it judges two signals as being completely uncorrelated (what we’d call antiphase). For anything in between, it gives you a continuously variable reading between the two polar extremes.

I use a phase correlator as a gut check when I fear something I’ve done may be too wide. For instance, I might like how wide a synth patch feels now that I’ve applied some stereo processing. However, my gut could tell me it would be lost in a mono playback system. The meters could verify this.

If the correlator gives me a troubling readout in spots, I’ll fold the song to mono and listen to see if anything has disappeared from the mix. That’s the meter and my ears working in concert as a checks-and-balance system.

Sidenote: good ol’ fashioned level meters are also handy phase tools, specifically for judging the polarity of your snare and toms against overheads. I’ll never forget watching Tory Amos’s engineer checking drum sounds in just this way: he would solo the snare and the overheads, and watch the meter on the overall output, and then flip the snare’s polarity. One configuration read inherently louder than the other, and this helped reinforce his decision to leave the snare alone. Then he repeated the steps with each tom; turns out the floor tom sounded better to him out of phase. He might’ve arrived at this conclusion by himself, but a careful eye on the lever meter ensured he got to the right decision for the mix.

What is metering not good for?

Let's start by addressing what metering is emphatically not good for. I’m doing this to dispel certain fearful notions and put fearful people at ease. See, many engineers recoil from the idea of metering as many musicians tend to recoil from music theory—the idea being that technique can hamper your innate sense of musicality or originality. If that has been your modus operandi in previous situations, I'd like to propose something right off the bat:

Metering is not a substitute for your ears. You are being paid for your ears—for the way your ears perceive, balance, and shape music. You’re not being paid to follow the guidelines of a meter and deliver products accordingly, because meters don’t hear music (at least not yet); they read an input signal and spit back information concerning that signal, be it related to frequency, level, polarity, or stereo spread. (Of course, the flipside is if you're mastering for broadcast or podcast—in which case that's exactly what you're getting paid for.)

Meters don’t measure how well a background vocal complements a lead part, whether that vocal should be dipped in level for a certain phrase, or if the vocal feels better on the right or left side of the stereo spectrum. That’s a relational and subjective choice, the actuation of which helps contribute to the goal of music. This is why metering, no matter how complex or newfangled, doesn’t replace the ear: a meter makes value judgments, while your ear makes artistic decisions.

But here’s the thing: you need value judgments to make artistic decisions. A cinematographer needs a light meter to help determine how to shoot the scene. Likewise, an architect needs a graphic scale to draw up plans with accurate dimensions. That’s mixing and mastering engineers use a visual aid, coupled with their ears, to make artistic decisions.

The advantages of using metering

The biggest advantage metering affords is a check on our subjectivity. But first, a question: what’s wrong with subjectivity anyway? After all, we’re being hired for our very subjectivity—that is what defines us, why our clients seek us out. Why would we need to temper this?

For the simple reason that our subjectivity can change drastically from one moment to the next. Anyone who’s mixed a song for more than three hours can attest to what I’m talking about. At a certain moment in the mix—or if you’re like me, moments in the plural—you reach “a dark night of the soul” in which everything begins to devolve; vibrancy becomes stale; second guessing becomes the first order of obsession.

I’ve long said that in these instances, reference tracks are our friends. And true, they are. But proper metering also becomes a safeguard against the negative side of subjectivity here. If we’re familiar with certain targets as they appear on a meter, we can check our work against the accepted averages of our field and continue to plough on through this dark night of the soul into a more glorious morning. Tonal Balance Control comes in handy here as well, as references can be loaded in and used to measure against a source track.

Why not just take a break here, when the going gets rough? Because we may not have the luxury. The client paid us to deliver the mix by morning, and morning is fast approaching; in such a situation all hands must report to the deck. We might have lost our objectivity, but a quick look over at the meter when EQing a troublesome passage or establishing the level of multiple songs might get us where we need to go until such a time as we can take a final break for the ear and listen afresh.

This is why we familiarize ourselves with meters, how they work, what they’re for, and the various standards associated with them. It is possible to create a good mix or master without them—but it’s much easier, and saves a lot more time, to just use them.